Related Research Articles

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is the divine force, quality and influence of God over the universe or his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as an agent of divine action or communication. In the Baha’i Faith, the Holy Spirit is seen as the intermediary between God and man and "the outpouring grace of God and the effulgent rays that emanate from His Manifestation".

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events relating to first-century Christianity. The New Testament's background, the first division of the Christian Bible, is called the Old Testament, which is based primarily upon the Hebrew Bible; together they are regarded as Sacred Scripture by Christians.

Rudolf Karl Bultmann was a German Lutheran theologian and professor of the New Testament at the University of Marburg. He was one of the major figures of early 20th-century biblical studies. A prominent critic of liberal theology, Bultmann instead argued for an existentialist interpretation of the New Testament. His hermeneutical approach to the New Testament led him to be a proponent of dialectical theology.

Raymond Edward Brown was an American Sulpician priest and prominent biblical scholar. He was a specialist on the hypothetical Johannine community, which he speculated contributed to the authorship of the Gospel of John, and he also wrote studies on the birth and death of Jesus.

Liberal Christianity, also known as liberal theology and historically as Christian Modernism, is a movement that interprets Christian teaching by taking into consideration modern knowledge, science and ethics. It emphasizes the importance of reason and experience over doctrinal authority. Liberal Christians view their theology as an alternative to both atheistic rationalism and theologies based on traditional interpretations of external authority, such as the Bible or sacred tradition.

Because scholars have tended to use the term in different ways, Biblical theology has been notoriously difficult to define. The academic field of biblical theology is sub-divided into Old Testament theology and New Testament theology.

The quest for the historical Jesus consists of academic efforts to determine what words and actions, if any, may be attributed to Jesus, and to use the findings to provide portraits of the historical Jesus. Since the 18th century, three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase. These quests are distinguished from earlier approaches because they rely on the historical method to study biblical narratives. While textual analysis of biblical sources had taken place for centuries, these quests introduced new methods and specific techniques to establish the historical validity of their conclusions.

Kerygma is a Greek word used in the New Testament for "proclamation". It is related to the Greek verb κηρύσσω (kērússō), literally meaning "to cry or proclaim as a herald" and being used in the sense of "to proclaim, announce, preach". Amongst biblical scholars, the term has come to mean the core of the early church's teaching about Jesus.

Reginald Horace Fuller was an English-American biblical scholar, ecumenist, and Anglican priest. His works are recognized for their consequential analysis of New Testament Christology. One aspect of his work is on the relation of Jesus to the early church and the church today. For this, his analysis, which uses the historical-critical method, has been described as neo-orthodox.

Roy Alvin Harrisville II was an American Lutheran theologian who wrote extensively on the interpretation of the New Testament.

The doctrine of the Trinity, considered the core of Christian theology by Trinitarians, is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325 in a way they believe is consistent with the biblical witness, and further refined in later councils and writings. The most widely recognized Biblical foundations for the doctrine's formulation are in the Gospel of John, which possess ideas reflected in Platonism and Greek philosophy.

Adolf Jülicher was a German scholar and biblical exegete. Specifically, he was the Professor of Church History and New Testament Exegesis, at the University of Marburg. He was born in Falkenberg near Berlin and died in Marburg.

Johannes Weiss was a German Protestant theologian and biblical exegete. He was a member of the history of religions school.

Walter Künneth was a German Protestant theologian. During the Nazi era, he was part of the Confessing Church, and in the 1960s took part in the debate around the demands of Rudolf Bultmann to 'de-mythologize' the New Testament as an advocate of a word-oriented interpretation of the Bible. The Walter Künneth Prize is named after him.

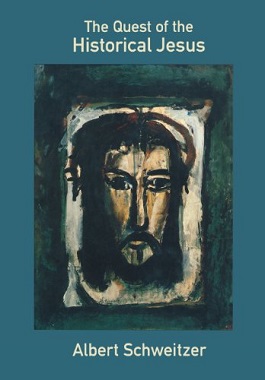

The Quest of the Historical Jesus is a 1906 work of Biblical historical criticism written by Albert Schweitzer during the previous year, before he began to study for a medical degree.

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the ministry of Jesus to the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles and is thus also known as the Apostolic Age. Early Christianity developed out of the eschatological ministry of Jesus. Subsequent to Jesus' death, his earliest followers formed an apocalyptic messianic Jewish sect during the late Second Temple period of the 1st century. Initially believing that Jesus' resurrection was the start of the end time, their beliefs soon changed in the expected Second Coming of Jesus and the start of God's Kingdom at a later point in time.

Peter Stuhlmacher is a Protestant theologian, professor emeritus of New Testament studies at the University of Tübingen.

Demythologization as a hermeneutic approach to religious texts seeks to separate or recover cosmological, sociological and historic claims from philosophical, ethical and theological teachings. Mostly applied to Biblical texts, demythologization often overlaps with philology, Biblical criticism and form criticism. The term demythologization was introduced by Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) in existential context, but the concept has earlier precedents.

Schubert Miles Ogden was an American Protestant theologian who proposed an interpretation of the Christian faith that he believes is both appropriate to the earliest apostolic witness found in the New Testament and also credible in the light of common human experience. He has written eleven books and been awarded many honors including the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, a Fulbright research scholarship, as well as honorary degrees from Ohio Wesleyan University, the University of Chicago, and Southern Methodist University. He has been invited to many titled lectureships in universities in Europe and the United States, made President of the American Academy of Religion (1976-7), and elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1985).

Ernst Fuchs was a German New Testament theologian and a student of Rudolf Bultmann. With Gerhard Ebeling he was a leading proponent of a New Hermeneutic theology in the 20th century.

References

- Bultmann, Rudolf (1955). Theology of the New Testament . Vol. 1–2. Translated by Grobel, Kendrick. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-41190-3.

- Jeremias, Joachim (1971). New Testament Theology: The Proclamation of Jesus . Translated by Bowden, John. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Matera, Frank J. (January 2005). "New Testament Theology: History, Method, and Identity". Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 67 (1): 1–21. JSTOR 43725389.

- Marshall, I. Howard (2004). New Testament Theology: Many Witnesses, One Gospel. IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-2795-4.

- "New Testament Theology". Encyclopedia of the Bible. Archived from the original on June 30, 2024.

- Rowe, C. Kavin (Summer 2006). "New Testament Theology: The Revival of a Discipline. A Review of Recent Contributions to the Field". Journal of Biblical Literature . 125 (2): 393–410. doi:10.2307/27638367. JSTOR 27638367.

- Schnabel, Eckhard J. (2023). New Testament Theology. Grand Rapids, Michigan, US: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-4306-2.

- Schnelle, Udo (2009). Theology of the New Testament. Translated by Boring, M. Eugene. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801036040.

- Scott, J. Julius, Jr. (September 2008). "Study of the Thematic Structure of the New Testament". Themelios. 33 (2).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stuhlmacher, Peter (2018). Biblical Theology of the New Testament. Translated by Bailey, Daniel P. William B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4080-6.

- Wrede, William (1973) [1897]. "The Tasks and Methods of 'New Testament Theology'". In Morgan, Robert (ed.). The Nature of New Testament Theology: The Contribution of William Wrede and Adolf Schlatter. Studies in Biblical Theology. London: Wipf and Stock. pp. 68–116. ISBN 9781606087077.