Related Research Articles

Bau, also read Baba or Babu (cuneiform: 𒀭𒁀𒌑 dBa-U2), was a Mesopotamian goddess. The reading of her name is a subject of debate among researchers, though Bau is considered the conventional spelling today. While initially regarded simply as a life-giving deity, in some cases associated with the creation in mankind, over the course of the third and second millennia BCE she also acquired the role of a healing goddess. She could be described as a divine midwife. In art she could be depicted in the company of waterfowl or scorpions.

Ninlil was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Enlil. She shared many of his functions, especially the responsibility for declaring destinies, and like him was regarded as a senior deity and head of the pantheon. She is also well attested as the mother of his children, such as the underworld god Nergal, the moon god Nanna or the warrior god Ninurta. She was chiefly worshiped in Nippur and nearby Tummal alongside Enlil, and multiple temples and shrines dedicated to her are attested in textual sources from these cities. In the first millennium BCE she was also introduced to Ḫursaĝkalamma near Kish, where she was worshiped alongside the goddess Bizilla, who was likely her sukkal.

Nisaba was the Mesopotamian goddess of writing and grain. She is one of the oldest Sumerian deities attested in writing, and remained prominent through many periods of Mesopotamian history. She was commonly worshiped by scribes, and numerous Sumerian texts end with the doxology "praise to Nisaba" as a result. She declined after the Old Babylonian period due to the rise of the new scribe god, Nabu, though she did not fully vanish from Mesopotamian religion and attestations from as late as the neo-Babylonian period are known.

Damu was a Mesopotamian god. While originally regarded as a dying god connected to vegetation, similar to Dumuzi or Ningishzida, with time he acquired the traits of a god of healing. He was regarded as the son of the medicine goddess Ninisina, or of her equivalents such as Gula or Ninkarrak. It is unclear which city was originally associated with him, but he is best attested in association with the cult center of his mother, Isin.

Pabilsaĝ was a Mesopotamian god. Not much is known about his role in Mesopotamian religion, though it is known that he could be regarded as a bow-armed warrior deity, as a divine cadastral officer or a judge. He might have also been linked to healing, though this remains disputed. In his astral aspect, first attested in the Old Babylonian period, he was a divine representation of the constellation Sagittarius.

Ninazu was a Mesopotamian god of the underworld of Sumerian origin. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. He was frequently associated with Ereshkigal, either as a son, husband, or simply as a deity belonging to the same category of underworld gods.

Abu was a Mesopotamian god. His character is poorly understood, though it is assumed he might have been associated with vegetation and with snakes. He was often paired with the deity gu2-la2, initially regarded as distinct from Gula, but later conflated with her.

Ningirida was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Ninazu and mother of Ningishzida. Little is known about her character beyond her relation to these two gods.

Ama-arḫuš was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with compassion and healing or epithet of goddesses designating them as compassionate.

Gunura was a Mesopotamian goddess, best known as a daughter and member of the entourage of the medicine goddess Ninisina. She was also associated with other similar goddesses, Gula and Nintinugga. Her original cult center is unknown, though she was worshiped in Isin, Nippur, Ur, Babylon and Assur. She is attested in a number of laments, in which she mourns the death of her brother Damu, and in a narrative about a journey of her mother Ninisina to Nippur.

Nungal, also known as Manungal and possibly Bēlet-balāṭi, was the Mesopotamian goddess of prisons, sometimes also associated with the underworld. She was worshiped especially in the Ur III period in cities such as Nippur, Lagash and Ur.

Ninegal or Belat Ekalli (Belet-ekalli) was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with palaces. Both her Sumerian and Akkadian name mean "lady of the palace."

Ninkarrak was a goddess of medicine worshiped chiefly in northern Mesopotamia and Syria. It has been proposed that her name originates in either Akkadian or an unidentified substrate language possibly spoken in parts of modern Syria, rather than in Sumerian. It is presumed that inconsistent orthography reflects ancient scholarly attempts at making it more closely resemble Sumerian theonyms. The best attested temples dedicated to her existed in Sippar and in Terqa. Finds from excavations undertaken at the site of the latter were used as evidence in more precisely dating the history of the region. Further attestations are available from northern Mesopotamia, including the kingdom of Apum, Assyria, and the Diyala area, from various southern Mesopotamian cities such as Larsa, Nippur, and possibly Uruk, as well as from Ugarit and Emar. It is possible that references to "Ninkar" from the texts from Ebla and Nikarawa, attested in Luwian inscriptions from Carchemish, were about Ninkarrak.

Ninisina was a Mesopotamian goddess who served as the tutelary deity of the city of Isin. She was considered a healing deity. She was believed to be skilled in the medical arts, and could be described as a divine physician or midwife. As an extension of her medical role, she was also believed to be capable of expelling various demons. Her symbols included dogs, commonly associated with healing goddesses in Mesopotamia, as well as tools and garments associated with practitioners of medicine.

Ninsianna was a Mesopotamian deity considered to be the personification of Venus. This theonym also served as the name of the planet in astronomical texts until the end of the Old Babylonian period. There is evidence that Ninsianna's gender varied between locations, and both feminine and masculine forms of this deity were worshiped. Due to their shared connection to Venus, Ninsianna was associated with Inanna. Furthermore, the deity Kabta appears alongside Ninsianna in many texts, but the character of the relation between them remains uncertain.

Gula was a Mesopotamian goddess of medicine, portrayed as a divine physician and midwife. Over the course of the second and first millennia BCE, she became one of the main deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon, and eventually started to be viewed as the second highest ranked goddess after Ishtar. She was associated with dogs, and could be depicted alongside these animals, for example on kudurru, and receive figurines representing them as votive offerings.

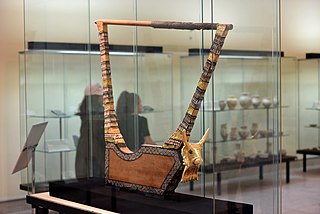

Ningizibara, also known as Igizibara and Ningizippara, was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with the balaĝ instrument, usually assumed to be a type of lyre. She could be regarded both as a physical instrument and as a minor deity. In both cases, she was associated with the goddess Inanna. A connection between her and the medicine goddess Gula is also attested, and it is possible she could serve as a minor healing deity herself.

Meme or Memešaga was a Mesopotamian goddess possibly regarded as a divine caretaker. While originally fully separate, she eventually came to be treated as one and the same as Gula, and as such came to be associated with medicine. The god list An = Anum additionally indicates she served as the sukkal of Ningal.

Ninnibru, also romanized as Nin-Nibru, was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Ninurta. She is attested in sources from between the Ur III and Kassite periods, including offering lists, the god list An = Anum, and the poem Angim. Later she came to be absorbed by Gula, and ceased to be worshiped as a separate deity.

Bulluṭsa-rabi was a Babylonian author and āšipu who most likely lived in the Kassite period. While sources from the first millennium BCE indicate at the time it was assumed that Bulluṭsa-rabi was a man, and this assumption was also initially followed by Assyriologists, further research showed that all individuals bearing this name recorded in earlier sources were women. A composition known from Nineveh, the Catalogue of Texts and Authors, attributes the authorship of a well known hymn to Gula and a number of unidentified texts to her.

References

- 1 2 3 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Böck 2015, p. 329.

- 1 2 Peterson 2009, p. 237.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 147.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 148.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 159.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 149.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 158.

- ↑ Böck 2015, p. 330.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 118.

- ↑ Wiggermann 1998, p. 331.

- 1 2 3 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 Böck 2015, p. 331.

- 1 2 3 4 Edzard 1998, p. 506.

- ↑ Katz 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 47.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 173.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 86.

- ↑ Peterson 2009, p. 234.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 14.

- 1 2 Böck 2015, p. 328.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 156.

- ↑ Westenholz 2010, p. 396.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 82.

- ↑ Westenholz 2010, p. 385.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 100.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 115.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 116.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 101.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 73.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 196-197.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 63.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 280.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 131.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 160.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 153.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 84.

- ↑ Beaulieu 1995, p. 91.

Bibliography

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-04. *Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1995). "The Brewers of Nippur". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 47. American Schools of Oriental Research: 85–96. doi:10.2307/1359817. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359817 . Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- Böck, Barbara (2015). "Ancient Mesopotamian Religion: A Profile of the Healing Goddess". Religion Compass. 9 (10). Wiley: 327–334. doi:10.1111/rec3.12165. hdl: 10261/125303 . ISSN 1749-8171. S2CID 145349556.

- Edzard, Dietz-Otto (1998), "Nin-tin-uga, Nin-tila-uga", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-08-23

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- Katz, Dina (2003). The Image of the Netherworld in the Sumerian Sources. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-77-3. OCLC 51770219.

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2009). "Two New Sumerian Texts Involving The Netherworld and Funerary Offerings". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 99 (2). doi:10.1515/ZA.2009.006. S2CID 162329196.

- Sibbing-Plantholt, Irene (2022). The Image of Mesopotamian Divine Healers. Healing Goddesses and the Legitimization of Professional Asûs in the Mesopotamian Medical Marketplace. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-51241-2. OCLC 1312171937.

- Westenholz, Joan G. (2010). "Ninkarrak – an Akkadian goddess in Sumerian guise". Von Göttern und Menschen. Brill. pp. 377–405. doi:10.1163/9789004187474_020. ISBN 9789004187481.

- Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998), "Nin-azu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2021-10-01