Macha was a sovereignty goddess of ancient Ireland associated with the province of Ulster, particularly the sites of Navan Fort and Armagh, which are named after her. Several figures called Macha appear in Irish mythology and folklore, all believed to derive from the same goddess. She is said to be one of three sisters known as 'the three Morrígna'. Like other sovereignty goddesses, Macha is associated with the land, fertility, kingship, war and horses.

Cessair or Cesair is a character from a medieval Irish origin myth, best known from the 11th-century chronicle text Lebor Gabála Érenn. According to the Lebor Gabála, she was the leader of the first inhabitants of Ireland, arriving before the Biblical flood. The tale may have been an attempt to Christianize an earlier pagan myth.

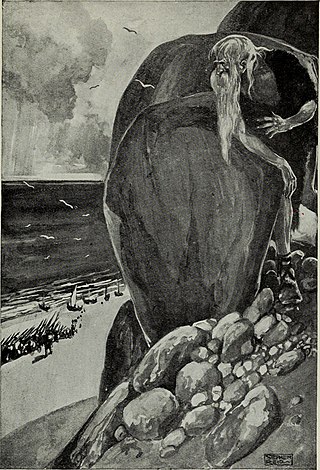

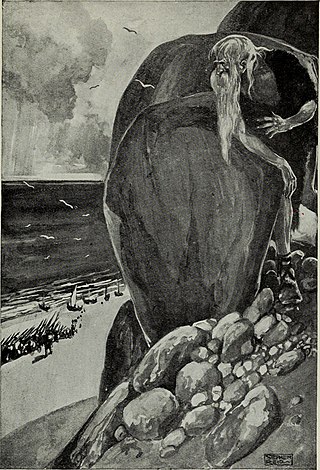

Nemed or Nimeth is a character in medieval Irish legend. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn, he was the leader of the third group of people to settle in Ireland: the Muintir Nemid, Clann Nemid or "Nemedians". They arrived thirty years after the Muintir Partholóin, their predecessors, had died out. Nemed eventually dies of plague and his people are oppressed by the Fomorians. They rise up against the Fomorians, attacking their tower out at sea, but most are killed and the survivors leave Ireland. Their descendants become the Fir Bolg.

In Irish origin myths, Míl Espáine or Míl Espáne is the mythical ancestor of the final inhabitants of Ireland, the "sons of Míl" or Milesians, who represent the vast majority of the Irish Gaels. His father was Bile, son of Breogan. Modern historians believe he is a creation of medieval Irish Christian writers.

Cathair Mór, son of Feidhlimidh Fiorurghlas, a descendant of Conchobar Abradruad, was, according to Lebor Gabála Érenn, a High King of Ireland. He took power after the death of Fedlimid Rechtmar. Cathair ruled for three years, at the end of which he was killed by the Luaigne of Tara, led by Conn Cétchathach. The Lebor Gabála Érenn synchronises his reign with that of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (161–180). The chronology of Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates his reign to 113–116, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 119–122.

In the Mythological Cycle of early Irish literature, the four treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann are four magical items which the mythological Tuatha Dé Danann are supposed to have brought with them from the four island cities Murias, Falias, Gorias, and Findias when they arrived in Ireland.

Lebor Gabála Érenn is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language intended to be a history of Ireland and the Irish from the creation of the world to the Middle Ages. There are a number of versions, the earliest of which was compiled by an anonymous writer in the 11th century. It synthesised narratives that had been developing over the foregoing centuries. The Lebor Gabála tells of Ireland being settled six times by six groups of people: the people of Cessair, the people of Partholón, the people of Nemed, the Fir Bolg, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the Milesians. The first four groups are wiped out or forced to abandon the island; the fifth group represents Ireland's pagan gods, while the final group represents the Irish people.

Tigernmas, son of Follach, son of Ethriel, a descendant of Érimón, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical traditions, an early High King of Ireland.

The Mythological Cycle is a conventional grouping within Irish mythology. It consists of tales and poems about the god-like Tuatha Dé Danann, who are based on Ireland's pagan deities, and other mythical races such as the Fomorians and the Fir Bolg. It is one of the four main story 'cycles' of early Irish myth and legend, along with the Ulster Cycle, the Fianna Cycle and the Cycles of the Kings. The name "Mythological Cycle" seems to have gained currency with Arbois de Jubainville c. 1881–1883. James MacKillop says the term is now "somewhat awkward", and John T. Koch notes it is "potentially misleading, in that the narratives in question represent only a small part of extant Irish mythology". He prefers T Ó Cathasaigh's name, Cycle of the Gods. Important works in the cycle are the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Cath Maige Tuired, the Aided Chlainne Lir and Tochmarc Étaíne.

Ethriel, son of Íriel Fáid, according to medieval Irish legends and historical traditions, succeeded his father as High King of Ireland. During his reign he cleared six plains. He ruled for twenty years, until he was killed in the Battle of Rairiu by Conmáel in revenge for his father Éber Finn, who had been killed by Ethriel's grandfather Érimón. He was the last of the chieftains who arrived in the invasion of the sons of Míl to rule Ireland. The Lebor Gabála Érenn says that during his reign Tautanes, king of Assyria, died, as did Hector and Achilles, and Samson was king of the Tribe of Dan in ancient Israel. Geoffrey Keating dates his reign from 1259 to 1239 BC, the Annals of the Four Masters from 1671 to 1651 BC.

Eochaid or Eochu Étgudach or Etgedach ('negligent'?), son of Dáire Doimthech, son of Conghal, son of Eadaman, son of Mal, son of Lugaid, son of Íth, son of Breogán, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn he was chosen as king by the remaining quarter of the men of Ireland after the other three-quarters had died with the former king, Tigernmas, while worshipping the deity Crom Cruach. He introduced a system whereby the number of colours a man could wear in his clothes depended on his social rank, from one colour for a slave to seven for a king or queen. He ruled for four years, until he was killed in battle at Tara by Cermna Finn, who succeeded to the throne jointly with his brother Sobairce. His reign is synchronised with that of Eupales in Assyria. The chronology of Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates his reign to 1159–1155 BC, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 1537–1533 BC.

In Irish mythology, Cichol or Cíocal Gricenchos is the earliest-mentioned leader of the Fomorians. His epithet, Gricenchos or Grigenchosach, is obscure. Macalister translates it as "clapperleg"; Comyn as "of withered feet". O'Donovan leaves it untranslated.

Muinemón, son of Cas Clothach, son of Irárd, son of Rothechtaid, son of Ros, son of Glas, son of Nuadu Declam, son of Eochaid Faebar Glas, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He helped Fíachu Fínscothach to murder his father, Sétna Airt, and become High King, and then, twenty years later, killed Fíachu and became High King himself. He is said to have been the first king in Ireland whose followers wore golden torcs around their necks. He ruled for five years, until he died of plague at Aidne in Connacht, and was succeeded by his son Faildergdóit. The chronology of Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates his reign to 955–950 BC, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 1333–1328 BC.

EochuUairches, son of Lugaid Íardonn, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. After Lugaid was overthrown and killed by Sírlám, Eochu was driven into exile overseas, but he returned after twelve years, killed Sírlám with an arrow, and took the throne. His epithet is obscure: the Lebor Gabála Érenn says he gained it because of his exile, while Geoffrey Keating explains it as meaning "bare canoes", because he had canoes for a fleet, in which he and his followers used to plunder neighbouring countries. He ruled for twelve years, before he was killed by Eochu Fíadmuine and Conaing Bececlach. The Lebor Gabála synchronises his reign with that of Artaxerxes I of Persia. The chronology of Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates his reign to 633–621 BC, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 856–844 BC.

Airgetmar, son of Sirlám, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. The Lebor Gabála Érenn says that, during the reign of Ailill Finn, he killed Fíachu Tolgrach in battle, but was forced into exile overseas by Ailill's son Eochu, Lugaid son of Eochu Fíadmuine, and the men of Munster. He returned to Ireland after seven years, and, with the help of Dui Ladrach, killed Ailill. Eochu became king, but Airgetmar and Dui soon killed him as well, and Airgetmar took power.

Lóegaire Lorc, son of Úgaine Mor, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. The Lebor Gabála Érenn says he succeeded directly after his father was murdered by Bodbchad, although Geoffrey Keating and the Annals of the Four Masters agree that Bodbchad seized power for a day and a half before Lóegaire killed him. He ruled for two years. His brother Cobthach Cóel Breg coveted the throne, and, taking the advice of a druid, pretended to be sick so Lóegaire would visit him. When he arrived, Cobthach feigned death, and when Lóegaire was bent over his body in mourning, stabbed him in with a dagger. Cobthach then paid someone to poison Lóegaire's son Ailill Áine, and forced Ailill's son Labraid to eat his father's and grandfather's hearts and a mouse, before forcing him into exile, supposedly because it was said that Labraid was the most hospitable man in Ireland. The Lebor Gabála synchronises his reign to that of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The chronology of Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates Bodbchad's reign to 411–409 BC, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 594–592 BC.

Bresal Bó-Díbad, son of Rudraige, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He took power after killing his predecessor, Finnat Már, and ruled for eleven years, during which there was a plague on cattle which left only one bull and one heifer alive.

Crimthann Nia Náir, son of Lugaid Riab nDerg, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. Lugaid is said to have fathered him on his own mother, Clothru, daughter of Eochu Feidlech. Clothru was thus both his mother and his grandmother.

Mag Itha, Magh Ithe, or Magh Iotha was, according to Irish mythology, the site of the first battle fought in Ireland. Medieval sources estimated that the battle had taken place between 2668 BCE and 2580 BCE. The opposing sides comprising the Fomorians, led by Cichol Gricenchos, and the followers of Partholón.

Cáelbad, son of Cronn Badhraoi, a descendant of Mal mac Rochride, was, according to Lebor Gabála Érenn, a High King of Ireland for a period of one year. Inneacht daughter of Lughaidh was the mother of Caolbhaidh son of Cronn Badhraoi; and he was slain by Eochaid Mugmedon. The chronology of Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn dates his reign to 343–344, that of the Annals of the Four Masters to 356–357.