Related Research Articles

The history of Greenland is a history of life under extreme Arctic conditions: currently, an ice sheet covers about eighty percent of the island, restricting human activity largely to the coasts. The first humans are thought to have arrived in Greenland around 2500 BCE. Their descendants apparently died out and were succeeded by several other groups migrating from continental North America. There has been no evidence discovered that Greenland was known to Norsemen until the ninth century CE, when Norse Icelandic explorers settled on its southwestern coast. The ancestors of the Greenlandic Inuit who live there today appear to have migrated there later, around the year 1200, from northwestern Greenland.

Ellesmere Island is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of 196,236 km2 (75,767 sq mi), slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total length of the island is 830 km (520 mi).

Baffin Island, in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada, the second largest island in the Americas, and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is 507,451 km2 (195,928 sq mi) with a population density of 0.03/km2; the population was 13,039 according to the 2021 Canadian census; and it is located at 68°N70°W. It also contains the city of Iqaluit, which is the capital of Nunavut.

The Beothuk were a group of Indigenous people who lived on the island of Newfoundland.

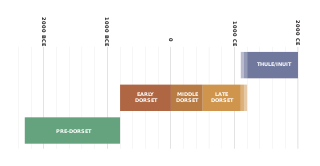

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation "Thule" originates from the location of Thule in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer's Midden.

The Norse exploration of North America began in the late 10th century, when Norsemen explored areas of the North Atlantic colonizing Greenland and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of Newfoundland. This is known now as L'Anse aux Meadows where the remains of buildings were found in 1960 dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. This discovery helped reignite archaeological exploration for the Norse in the North Atlantic. This single settlement, located on the island of Newfoundland and not on the North American mainland, was abruptly abandoned.

Markland is the name given to one of three lands on North America's Atlantic shore discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD. It was located south of Helluland and north of Vinland.

Skræling is the name the Norse Greenlanders used for the peoples they encountered in North America. In surviving sources, it is first applied to the Thule people, the proto-Inuit group with whom the Norse coexisted in Greenland after about the 13th century. In the sagas, it is also used for the peoples of the region known as Vinland whom the Norse encountered and fought during their expeditions there in the early 11th century.

The Maine penny, also referred to as the Goddard coin, is a Norwegian silver coin dating to the reign of Olaf Kyrre King of Norway (1067–1093 AD). It was claimed to be discovered in Maine in 1957, and it has been suggested as evidence of Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact.

Helluland is the name given to one of the three lands, the others being Vinland and Markland, seen by Bjarni Herjólfsson, encountered by Leif Erikson and further explored by Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson around AD 1000 on the North Atlantic coast of North America. As some writers refer to all land beyond Greenland as Vinland; Helluland is sometimes considered a part of Vinland.

The history of Nunavut covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Eskimo thousands of years ago to present day. Prior to the colonization of the continent by Europeans, the lands encompassing present-day Nunavut were inhabited by several historical cultural groups, including the Pre-Dorset, the Dorsets, the Thule and their descendants, the Inuit.

James A. Tuck, was an American-born archaeologist whose work as a faculty member of the Memorial University of Newfoundland was focused on the early history of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the Nunavut Act and the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act, which provided this territory to the Inuit for independent government. The boundaries had been drawn in 1993. The creation of Nunavut resulted in the first major change to Canada's political map in half a century since the province of Newfoundland was admitted in 1949.

Based on archeological finds, Brooman Point Village is an abandoned village in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the central High Arctic near Brooman Point of the Gregory Peninsula, part of the eastern coast of Bathurst Island. Brooman was both a Late Dorset culture Paleo-Eskimo village as well as an Early Thule culture village. Both the artifacts and the architecture, specifically longhouses, are considered important historical remains of the two cultures. The site shows traces of Palaeo-Eskimo occupations between about 2000 BC and 1 AD, but the major prehistoric settlement occurred from about 900 to 1200 AD.

L'Anse aux Meadows is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador near St. Anthony.

William Wyvill Fitzhugh IV is an American archaeologist and anthropologist who directs the Smithsonian’s Arctic Studies Center and is a Senior Scientist at the National Museum of Natural History. He has conducted archaeological research throughout the circumpolar region investigating cultural responses to climate and environmental change and European contact. He has published numerous books and more than 150 journal articles, and has produced large international exhibitions and popular films. Of particular note are the many exhibition catalogues he has had edited, which make syntheses of scholarly research on these subjects available to visitors to public exhibitions.

Tanfield Valley, also referred to as Nanook, is an archaeological site located on Imiligaarjuit, along the southernmost part of the Meta Incognita Peninsula of Baffin Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. It is possible that during the Pre-Columbian era the site was known to Norse explorers from Greenland and Iceland. It may be in the region of Helluland, spoken of in the Vinland sagas.

Point Rosee, previously known as Stormy Point, is a headland near Codroy at the southwest end of the island of Newfoundland, on the Atlantic coast of Canada.

References

- ↑ Staff & Faculty, Geography and Environmental Studies, Carleton University, retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ↑ Honorary Staff, Researchers & Emeritus Staff, School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen.

- 1 2 3 "The Norse: An Arctic Mystery", The Nature of Things , CBC Television, November 22, 2012. Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Wayback Machine, November 27, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Don Butler, "Fired Arctic archeologist Patricia Sutherland seeks access to research", Ottawa Citizen , March 5, 2014, updated May 20, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Margo Pfeiff, "When the Vikings were in Nunavut" Archived 2016-04-18 at the Wayback Machine , Up Here, July 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Has Political Correctness Sunk the Baffin Island Viking Research Project?", The New Observer , November 27, 2012.Alternative web address

- ↑ "Silence of the Labs", The Fifth Estate , Season 39, January 10, 2014.

- 1 2 Owen Jarus, "Searching for the Vikings: 3 Sites Possibly Found in Canada", Live Science , April 18, 2016.

- ↑ Shelley Wright, Our Ice Is Vanishing / Sikuvut Nunguliqtuq: A History of Inuit, Newcomers, and Climate Change, McGill-Queen's Native and Northern Series 75, Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2014, ISBN 9780773596108, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Don Butler, "History museum staff raised ethical objections to acquisition of Empress of Ireland collection", Ottawa Citizen, January 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Wendy Stueck and Kate Taylor, "Canadian Museum of History reveals researcher was fired for harassment", The Globe and Mail , December 4, 2014, updated December 5, 2014.

- ↑ J. J. McCullough, "Media Bites: Want to Hear How Harper Hates Science? Watch CBC", blog, Huffington Post , January 13, 2014, updated March 15, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Jane George, "Kimmirut site suggests early European contact" Archived 2009-08-19 at the Wayback Machine , Nunatsiaq News , September 12, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Heather Pringle "Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada", National Geographic , October 19, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Armstrong, Jane (20 November 2012). "Vikings in Canada?". A researcher says she's found evidence that Norse sailors may have settled in Canada's Arctic. Others aren't so sure. Maclean's . Retrieved 15 January 2019.

In fact, Fitzhugh thinks the cord at the centre of Sutherland's "eureka" moment is a Dorset artifact. "We have very good evidence that this kind of spun cordage was being used hundreds of years before the Norse arrived in the New World, in other words 500 to 600 CE, at the least," he says.

- ↑ Colin Nickerson, The Boston Globe , "Canadian digs indicate wider Viking travels", Eugene Register-Guard , February 5, 2000, p. 12A.

- ↑ Patricia D. Sutherland, Peter H. Thompson and Patricia A. Hunt, "Evidence of Early Metalworking in Arctic Canada", Geoarchaeology 30.1 (January/February 2015) 74–78, DOI: 10.1002/gea.21497.

- ↑ "Fired Canadian researcher unveils new discovery about European contact in the Arctic", As It Happens , CBC Radio One, July 17, 2015 (audio).

- 1 2 Weber, Bob (22 July 2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC . Retrieved 2 January 2019.

… Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University in Rhode Island, lead author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Hayeur Smith and her colleagues were looking at scraps of yarn, perhaps used to hang amulets or decorate clothing, from ancient sites on Baffin Island and the Ungava Peninsula. The idea that you would have to learn to spin something from another culture was a bit ludicrous," she said. "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do.

- 1 2 Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1992) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press, "We now have at least two pieces of evidence that this important principle of twisting for strength dates to the Palaeolithic. In 1953, the Abbé Glory was investigating floor deposits in a steep corridor of the famed Lascaux caves in southern France […] a long piece of Palaeolithic cord […] neatly twisted in the S direction […] from three Z-plied strands […]" ISBN 0-691-00224-X

- 1 2 Smith, Michèle Hayeur; Smith, Kevin P.; Nilsen, Gørill (August 2018). "Journal of Archaeological Science" (PDF). Dorset, Norse, or Thule? Technological Transfers, Marine Mammal Contamination, and AMS Dating of Spun Yarn and Textiles from the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/J.JAS.2018.06.005. S2CID 52035803. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-13. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

However, the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers. [. . .] Our investigations indicate that Paleoeskimo (Dorset) communities on Baffin Island spun threads from the hair and also from the sinews of native terrestrial grazing animals, most likely musk ox and arctic hare, throughout the Middle Dorset period and for at least a millennium before there is any reasonable evidence of European activity in the islands of the North Atlantic or in the North American Arctic

- ↑ "The Norse: An Arctic Mystery". The Nature of Things CBC Television. November 22, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

pieces that weren't made by indigenous hands, but by Norse traders

at the Wayback Machine, November 27, 2012. - ↑ Upside Down: Arctic Realities, Edmund Carpenter editor. Houston: Menil Foundation, 2011, ISBN 9780300169386.