Poseidon is one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses. He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cities and colonies. In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, Poseidon was venerated as a chief deity at Pylos and Thebes, with the cult title "earth shaker"; in the myths of isolated Arcadia, he is related to Demeter and Persephone and was venerated as a horse, and as a god of the waters. Poseidon maintained both associations among most Greeks: He was regarded as the tamer or father of horses, who, with a strike of his trident, created springs. His Roman equivalent is Neptune.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Hestia is the virgin goddess of the hearth, the right ordering of domesticity, the family, the home, and the state. In myth, she is the firstborn child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, and one of the Twelve Olympians.

Tantalus was a Greek mythological figure, most famous for his punishment in Tartarus: he was made to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree with low branches, with the fruit ever eluding his grasp, and the water always receding before he could take a drink. He was also called Atys.

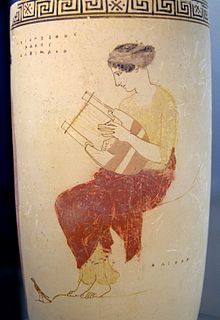

Bacchylides was a Greek lyric poet. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets, which included his uncle Simonides. The elegance and polished style of his lyrics have been noted in Bacchylidean scholarship since at least Longinus. Some scholars have characterized these qualities as superficial charm. He has often been compared unfavourably with his contemporary, Pindar, as "a kind of Boccherini to Pindar's Haydn". However, the differences in their styles do not allow for easy comparison, and translator Robert Fagles has written that "to blame Bacchylides for not being Pindar is as childish a judgement as to condemn ... Marvell for missing the grandeur of Milton". His career coincided with the ascendency of dramatic styles of poetry, as embodied in the works of Aeschylus or Sophocles, and he is in fact considered one of the last poets of major significance within the more ancient tradition of purely lyric poetry. The most notable features of his lyrics are their clarity in expression and simplicity of thought, making them an ideal introduction to the study of Greek lyric poetry in general and to Pindar's verse in particular.

Simonides of Ceos was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed by them as worthy of critical study. Included on this list were Bacchylides, his nephew, and Pindar, reputedly a bitter rival, both of whom benefited from his innovative approach to lyric poetry. Simonides, however, was more involved than either in the major events and with the personalities of their times.

HieronI was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

In Greek mythology, Augeas, whose name means "bright", was king of Elis and father of Epicaste. Some say that Augeas was one of the Argonauts. He is known for his stables, which housed the single greatest number of cattle in the country and had never been cleaned, until the time of the great hero Heracles.

Pindar was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is by far the greatest, in virtue of his inspired magnificence, the beauty of his thoughts and figures, the rich exuberance of his language and matter, and his rolling flood of eloquence, characteristics which, as Horace rightly held, make him inimitable." His poems can also, however, seem difficult and even peculiar. The Athenian comic playwright Eupolis once remarked that they "are already reduced to silence by the disinclination of the multitude for elegant learning". Some scholars in the modern age also found his poetry perplexing, at least until the 1896 discovery of some poems by his rival Bacchylides; comparisons of their work showed that many of Pindar's idiosyncrasies are typical of archaic genres rather than of only the poet himself. His poetry, while admired by critics, still challenges the casual reader and his work is largely unread among the general public.

In Greek mythology, Iamus was the son of Apollo and Evadne, a daughter of Poseidon, raised by Aepytus.

In Greek mythology, Astydamea or Astydamia is a name attributed to several individuals:

In Greek mythology, Rhodos/Rhodus or Rhode, was the goddess and personification of the island of Rhodes and a wife of the sun god Helios.

Menoetius or Menoetes, meaning doomed might, is a name that refers to three distinct beings from Greek mythology:

In Greek mythology, Pelops was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region. He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

Hippodamia was a Greek mythological figure. She was the queen of Pisa and the wife of Pelops, appearing with Pelops at a potential cult site in Ancient Olympia.

In Greek mythology, Minyas was the founder of Orchomenus, Boeotia.

In Greek mythology, Pirene or Peirene, a nymph, was either the daughter of the river god Asopus, Laconian king Oebalus, or the river god Achelous, depending on different sources. By Poseidon she became the mother of Lecheas and Cenchrias.

Euryalus refers to the Euryalus fortress, the main citadel of Ancient Syracuse, and to several different characters from Greek mythology and classical literature:

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the twelve Olympians are the major deities of the Greek pantheon, commonly considered to be Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Aphrodite, Athena, Artemis, Apollo, Ares, Hephaestus, Hermes, and either Hestia or Dionysus. They were called Olympians because, according to tradition, they resided on Mount Olympus.

Pherenikos was an Ancient Greek chestnut racehorse victorious at the Olympic and Pythian Games in the 470s BC. Pherenikos, whose name means "victory-bearer", was "the most famous racehorse in antiquity". Owned by Hieron I, tyrant of Syracuse, Pherenikos is celebrated in the victory odes of both Pindar and Bacchylides.

In Greek mythology, Eurymedon was the name of several minor figures: