The Genesee River is a tributary of Lake Ontario flowing northward through the Twin Tiers of Pennsylvania and New York in the United States. The river contains several waterfalls in New York at Letchworth State Park and Rochester.

Watkins Glen State Park is in the village of Watkins Glen, south of Seneca Lake in Schuyler County in New York's Finger Lakes region. The park's lower part is near the village, while the upper part is open woodland. It was opened to the public in 1863 and was privately run as a tourist resort until 1906, when it was purchased by New York State. Initially known as Watkins Glen State Reservation, the park was first managed by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society before being turned over to full state control in 1911. Since 1924, it has been managed by the Finger Lakes Region of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a national park of the United States in Ohio that preserves and reclaims the rural landscape along the Cuyahoga River between Akron and Cleveland in Northeast Ohio.

Tinker's Creek, in Cuyahoga, Summit and Portage counties of Ohio, is the largest tributary of the Cuyahoga River, providing about a third of its flow into Lake Erie.

The Chagrin River is located in Northeast Ohio. The river has two branches, the Aurora Branch and East Branch. Of three hypotheses as to the origin of the name, the most probable is that it is a corruption of the name of a Frenchman, Sieur de Seguin, who established a trading post on the river ca. 1742. The Chagrin River runs through suburban areas of Greater Cleveland in Cuyahoga, Geauga, and Portage counties, transects two Cleveland Metroparks reservations, and then meanders into nearby Lake County before emptying into Lake Erie.

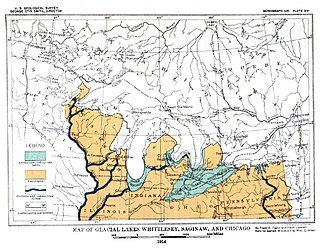

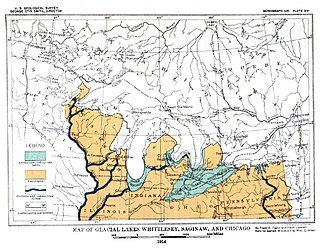

Lake Maumee was a proglacial lake and an ancestor of present-day Lake Erie. It formed about 17,500 calendar years, or 14,000 Radiocarbon Years Before Present (RCYBP) as the Huron-Erie Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation. As water levels continued to rise the lake evolved into Lake Arkona and then Lake Whittlesey.

The Appalachian Highlands is one of eight government-defined physiographic divisions of the contiguous United States. It links with the Appalachian Uplands in Canada to make up the Appalachian Mountains. The Highlands includes seven physiographic provinces, which is the second level in the physiographic classification system in the United States. At the next level of physiographic classification, called section/subsection, there are 20 unique land areas with one of the provinces having no sections.

Gildersleeve Mountain is a summit located in Kirtland, Ohio, United States.

The Valparaiso Moraine is a recessional moraine that forms an immense U around the southern Lake Michigan basin in North America. It is a band of hilly terrain composed of glacial till and sand. The Valparaiso Moraine defines part of the continental divide known as the Saint Lawrence River Divide, bounding the Great Lakes Basin. It begins near the border of Wisconsin and Illinois and extends south through Lake, McHenry, Cook, DuPage and Will counties in Illinois, and then turns southeast, going through northwestern Indiana. From this point, the moraine curves northeast through Lake, Porter, and LaPorte counties of Indiana into Michigan. It continues into Michigan as far as Montcalm County.

The Bedford Shale is a shale geologic formation in the states of Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia in the United States.

The Queenston Formation is a geological formation of Upper Ordovician age, which outcrops in Ontario, Canada and New York, United States. A typical outcrop of the formation is exposed at Bronte Creek just south of the Queen Elizabeth Way. The formation is a part of the Queenston Delta clastic wedge, formed as an erosional response to the Taconic Orogeny. Lithologically, the formation is dominated by red and grey shales with thin siltstone, limestone and sandstone interlayers. As materials, comprising the clastic wedge, become coarser in close proximity to the Taconic source rocks, siltstone and sandstone layers are predominant in New York.

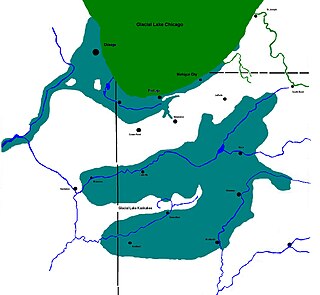

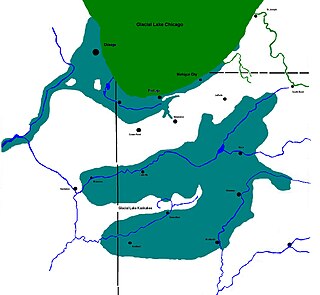

Lake Kankakee formed 14,000 years before present (YBP) in the valley of the Kankakee River. It developed from the outwash of the Michigan Lobe, Saginaw Lobe, and the Huron-Erie Lobe of the Wisconsin glaciation. These three ice sheets formed a basin across Northwestern Indiana. It was a time when the glaciers were receding, but had stopped for a thousand years in these locations. The lake drained about 13,000 YBP, until reaching the level of the Momence Ledge. The outcropping of limestone created an artificial base level, holding water throughout the upper basin, creating the Grand Kankakee Marsh.

Lake Whittlesey was a proglacial lake that was an ancestor of present-day Lake Erie. It formed about 14,000 years ago. As the Erie Lobe of the Wisconsin Glacier retreated at the end of the last ice age, it left melt-water in a previously-existing depression area that was the valley of an eastward-flowing river known as the Erigan River that probably emptied into the Atlantic Ocean following the route of today's Saint Lawrence River. The lake stood at 735 feet (224 m) to 740 feet (230 m) above sea level. The remanent beach is not horizontal as there is a ‘hinge line’ southwest of a line from Ashtabula, Ohio, through the middle part of Lake St. Clair. The hinge line is where the horizontal beaches of the lake have been warped upwards towards the north by the isostatic rebound as the weight of the ice sheet was removed from the land. The rise is 60 feet (18 m) north into Michigan and the Ubly outlet. The current altitude of the outlet is 800 feet (240 m) above sea level. Where the outlet entered the Second Lake Saginaw at Cass City the elevation is 740 feet (230 m) above sea level. The Lake Whittlesey beach called the Belmore Beach and is a gravel ridge 10 feet (3.0 m) to 15 feet (4.6 m) high and one-eighth mile wide. Lake Whittlesey was maintained at the level of the Ubly outlet only until the ice melted back on the "Thumb" far enough to open a lower outlet. This ice recession went far enough to allow the lake to drop about 20 feet (6.1 m) below the lowest of the Arkona beaches to Lake Warren levels.

Lake Arkona was a stage of the lake waters in the Huron-Erie-Ontario basin following the end of the Lake Maumee levels and before the Lake Whittlesey stages, named for Arkona, Ontario, about 50 miles (80 km) east of Sarnia.

Lake Wayne formed in the Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair basins around 12,500 years before present (YBP) when Lake Arkona dropped in elevation. About 20 feet (6.1 m) below the Lake Warren beaches it was early described as a lower Lake Warren level. Based on work in Wayne County, near the village of Wayne evidence was found that Lake Wayne succeeded Lake Whittlesey and preceded Lake Warren. From the Saginaw Basin the lake did not discharge water through Grand River but eastward along the edge of the ice sheet to Syracuse, New York, thence into the Mohawk valley. This shift in outlets warranted a separate from Lake Warren. The Wayne beach lies but a short distance inside the limits of the Warren beach. Its character is not greatly different when taken throughout its length in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. At the type locality in Wayne County, Michigan, it is a sandy ridge, but farther north, and to the east through Ohio it is gravel. The results of the isostatic rebound area similar to the Lake Warren beaches.

Lake Monongahela was a proglacial lake in western Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. It formed during the Pre-Illinoian ice epoch when the retreat of the ice sheet northwards blocked the drainage of these valleys to the north. The lake formed south of the ice front continued to rise until it was able to breach a low divide near New Martinsville, West Virginia. The overflow was the beginning of the process which created the modern Ohio River valley.

The Erie Plain is a lacustrine plain that borders Lake Erie in North America. From Buffalo, New York, to Cleveland, Ohio, it is quite narrow, but broadens considerably from Cleveland around Lake Erie to Southern Ontario, where it forms most of the Ontario peninsula. The Erie Plain was used in the United States as a natural gateway to the North American interior, and in both the United States and Canada the plain is heavily populated and provides very fertile agricultural land.

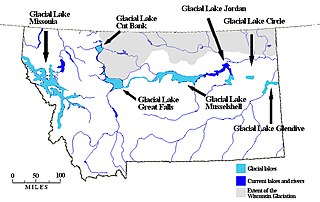

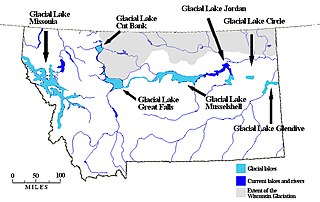

The basin that held Pleistocene Lake Musselshell is in the lower (north-flowing) reach of the river. It is underlain mostly by highly erodible Cretaceous Colorado shale, Montana group sandstone, siltstone and shale, and Hell Creek sandstone and shale. The bedrock is gently folded and affected by local faults and joints. There is a sequence of nine terraces and more than 100 glacial boulders. The terraces are older than the erratics as the erratics rest on the terraces.

Euclid Creek is a 43-mile (69 km) long stream located in Cuyahoga and Lake counties in the state of Ohio in the United States. The 11.5-mile (18.5 km) long main branch runs from the Euclid Creek Reservation of the Cleveland Metroparks to Lake Erie. The west branch is usually considered part of the main branch, and extends another 16 miles (26 km) to the creek's headwaters in Beachwood, Ohio. The east branch runs for 19 miles (31 km) and has headwaters in Willoughby Hills, Ohio.

The geology of Ohio formed beginning more than one billion years ago in the Proterozoic eon of the Precambrian. The igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rock is poorly understood except through deep boreholes and does not outcrop at the surface. The basement rock is divided between the Grenville Province and Superior Province. When the Grenville Province crust collided with Proto-North America, it launched the Grenville orogeny, a major mountain building event. The Grenville mountains eroded, filling in rift basins and Ohio was flooded and periodically exposed as dry land throughout the Paleozoic. In addition to marine carbonates such as limestone and dolomite, large deposits of shale and sandstone formed as subsequent mountain building events such as the Taconic orogeny and Acadian orogeny led to additional sediment deposition. Ohio transitioned to dryland conditions in the Pennsylvanian, forming large coal swamps and the region has been dryland ever since. Until the Pleistocene glaciations erased these features, the landscape was cut with deep stream valleys, which scoured away hundreds of meters of rock leaving little trace of geologic history in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic.