The Niagara Escarpment is a long escarpment, or cuesta, in Canada and the United States that starts from the south shore of Lake Ontario westward, circumscribes the top of the Great Lakes Basin running from New York through Ontario, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The escarpment is the cliff over which the Niagara River plunges at Niagara Falls, for which it is named.

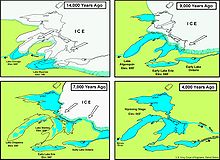

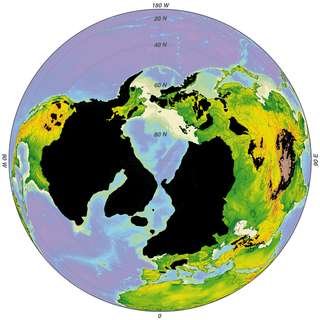

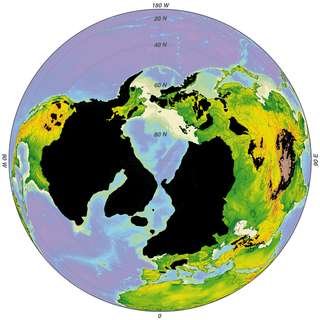

The Wisconsin Glacial Episode, also called the Wisconsin glaciation, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex. This advance included the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which nucleated in the northern North American Cordillera; the Innuitian ice sheet, which extended across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago; the Greenland ice sheet; and the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered the high latitudes of central and eastern North America. This advance was synchronous with global glaciation during the last glacial period, including the North American alpine glacier advance, known as the Pinedale glaciation. The Wisconsin glaciation extended from approximately 75,000 to 11,000 years ago, between the Sangamonian Stage and the current interglacial, the Holocene. The maximum ice extent occurred approximately 25,000–21,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum, also known as the Late Wisconsin in North America.

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region centered around the Great Lakes that includes eight U.S. states and the Canadian province of Ontario. Canada´s Quebec province is at times included as part of the region because the St. Lawrence River watershed is part of the continuous hydrologic system. The region forms a distinctive historical, economic, and cultural identity. A portion of the region also encompasses the Great Lakes megalopolis.

Lake Tonawanda was a prehistoric lake that existed approximately 10,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age, in Western New York, United States.

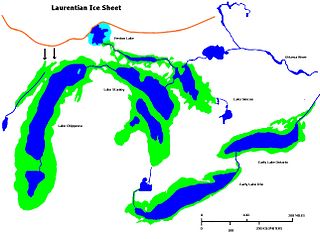

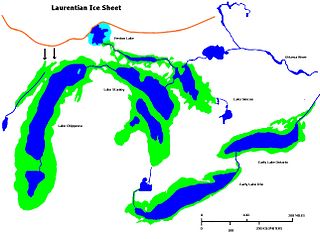

Lake Algonquin was a prehistoric proglacial lake that existed in east-central North America at the time of the last ice age. Parts of the former lake are now Lake Huron, Georgian Bay, Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Nipigon, and Lake Nipissing.

Early Lake Erie was a prehistoric proglacial lake that existed at the end of the last ice age approximately 13,000 years ago. The early Erie fed waters to Glacial Lake Iroquois.

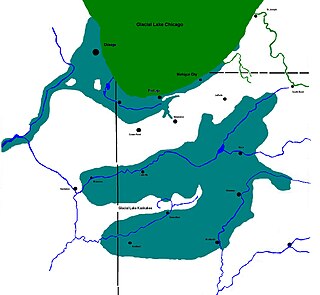

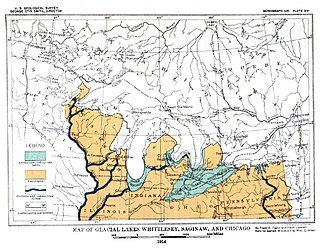

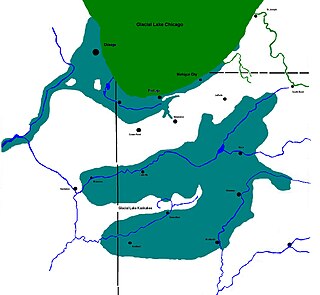

Lake Chicago was a prehistoric proglacial lake that is the ancestor of what is now known as Lake Michigan, one of North America's five Great Lakes. Formed about 13,000 years ago and fed by retreating glaciers, it drained south through the Chicago Outlet River.

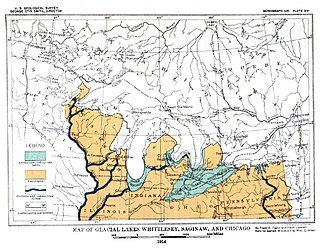

Lake Maumee was a proglacial lake and an ancestor of present-day Lake Erie. It formed about 17,500 calendar years, or 14,000 Radiocarbon Years Before Present (RCYBP) as the Huron-Erie Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation. As water levels continued to rise the lake evolved into Lake Arkona and then Lake Whittlesey.

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Lowlands, or simply St. Lawrence Lowlands, is a physiographic region of Eastern Canada that comprises a section of southern Ontario bounded on the north by the Canadian Shield and by 3 of the Great Lakes — Lake Huron, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario — and extends along the St. Lawrence River to the Strait of Belle Isle and the Atlantic Ocean. The lowlands comprise three sub-regions that were created by intrusions from adjacent physiographic regions — the West Lowland, Central Lowland and East Lowland. The West Lowland includes the Niagara Escarpment, extending from the Niagara River to the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. The Central Lowland stretches between the Ottawa River and the St. Lawrence River. The East Lowland includes Anticosti Island, Îles de Mingan, and extends to the Strait of Belle Isle.

The Valparaiso Moraine is a recessional moraine that forms an immense U around the southern Lake Michigan basin in North America. It is the longest moraine. It is a band of hilly terrain composed of glacial till and sand. The Valparaiso Moraine forms part of the Saint Lawrence River Divide, bounding the Great Lakes Basin. It begins near the border of Wisconsin and Illinois and extends south through Lake, McHenry, Cook, DuPage and Will counties in Illinois, and then turns southeast, going through northwestern Indiana. From this point, the moraine curves northeast through Lake, Porter, and LaPorte counties of Indiana into Michigan. It continues into Michigan as far as Montcalm County.

Admiralty Lake was a proglacial lake in the basin of what is now Lake Ontario. The shoreline of Admiralty Lake was about 20 metres (66 ft) lower than Lake Ontario. The shoreline of Glacial Lake Iroquois, an earlier proglacial lake, was much higher than Lake Ontario's, because a lobe of the Laurentian Glacier blocked what is now the valley of the St Lawrence River. Lake Iroquois drained over the Niagara Escarpment, and down the Mohawk River. When the lobe of the glacier retreated the weight of the glacier kept the outlet of the St Lawrence River lower than the current level. As the glacier continued to retreat the region of the Thousand Islands rebounded, and the lake filled to its current level.

Lake Kankakee formed 14,000 years before present (YBP) in the valley of the Kankakee River. It developed from the outwash of the Michigan Lobe, Saginaw Lobe, and the Huron-Erie Lobe of the Wisconsin glaciation. These three ice sheets formed a basin across Northwestern Indiana. It was a time when the glaciers were receding, but had stopped for a thousand years in these locations. The lake drained about 13,000 YBP, until reaching the level of the Momence Ledge. The outcropping of limestone created an artificial base level, holding water throughout the upper basin, creating the Grand Kankakee Marsh.

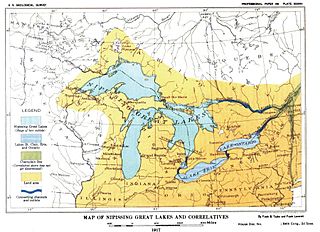

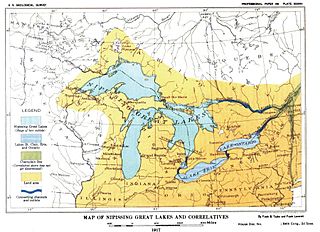

Nipissing Great Lakes was a prehistoric proglacial lake. Parts of the former lake are now Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Georgian Bay and Lake Michigan. It formed about 7,500 years before present (YBP). The lake occupied the depression left by the Labradorian Glacier. This body of water drained eastward from Georgian Bay to the Ottawa valley. This was a period of isostatic rebound raising the outlet over time, until it opened the outlet through the St. Clair valley.

Lake Whittlesey was a proglacial lake that was an ancestor of present-day Lake Erie. It formed about 14,000 years ago. As the Erie Lobe of the Wisconsin Glacier retreated at the end of the last ice age, it left melt-water in a previously-existing depression area that was the valley of an eastward-flowing river known as the Erigan River that probably emptied into the Atlantic Ocean following the route of today's Saint Lawrence River. The lake stood at 735 feet (224 m) to 740 feet (230 m) above sea level. The remanent beach is not horizontal as there is a ‘hinge line’ southwest of a line from Ashtabula, Ohio, through the middle part of Lake St. Clair. The hinge line is where the horizontal beaches of the lake have been warped upwards towards the north by the isostatic rebound as the weight of the ice sheet was removed from the land. The rise is 60 feet (18 m) north into Michigan and the Ubly outlet. The current altitude of the outlet is 800 feet (240 m) above sea level. Where the outlet entered the Second Lake Saginaw at Cass City the elevation is 740 feet (230 m) above sea level. The Lake Whittlesey beach called the Belmore Beach and is a gravel ridge 10 feet (3.0 m) to 15 feet (4.6 m) high and one-eighth mile wide. Lake Whittlesey was maintained at the level of the Ubly outlet only until the ice melted back on the "Thumb" far enough to open a lower outlet. This ice recession went far enough to allow the lake to drop about 20 feet (6.1 m) below the lowest of the Arkona beaches to Lake Warren levels.

Lake Arkona was a stage of the lake waters in the Huron-Erie-Ontario basin following the end of the Lake Maumee levels and before the Lake Whittlesey stages, named for Arkona, Ontario, about 50 miles (80 km) east of Sarnia.

Lake Warren was a proglacial lake that formed in the Lake Erie basin around 12,700 years before present (YBP) when Lake Whittlesey dropped in elevation. Lake Warren is divided into three stages: Warren I 690 feet (210 m), Warren II 680 feet (210 m), and Warren III 675 feet (206 m), each defined by the relative elevation above sea level.

Lake Wayne formed in the Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair basins around 12,500 years before present (YBP) when Lake Arkona dropped in elevation. About 20 feet (6.1 m) below the Lake Warren beaches it was early described as a lower Lake Warren level. Based on work in Wayne County, near the village of Wayne evidence was found that Lake Wayne succeeded Lake Whittlesey and preceded Lake Warren. From the Saginaw Basin the lake did not discharge water through Grand River but eastward along the edge of the ice sheet to Syracuse, New York, thence into the Mohawk valley. This shift in outlets warranted a separate from Lake Warren. The Wayne beach lies but a short distance inside the limits of the Warren beach. Its character is not greatly different when taken throughout its length in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. At the type locality in Wayne County, Michigan, it is a sandy ridge, but farther north, and to the east through Ohio it is gravel. The results of the isostatic rebound area similar to the Lake Warren beaches.

The Saint Lawrence River Divide is a continental divide in central and eastern North America that separates the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin from the southerly Atlantic Ocean watersheds. Water, including rainfall and snowfall, lakes, rivers and streams, north and west of the divide, drains into the Gulf of St. Lawrence or the Labrador Sea; water south and east of the divide drains into the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico. The divide is one of six continental divides in North America that demarcate several watersheds that flow to different gulfs, seas or oceans.

The Portage Escarpment is a major landform in the U.S. states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York which marks the boundary between the Till Plains to the north and west and the Appalachian Plateau to the east and south. The escarpment is the defining geological feature of New York's Finger Lakes region. Its proximity to Lake Erie creates a narrow but easily traveled route between upstate New York and the Midwest. Extensive industrial and residential development occurred along this route.

Euclid Creek is a 43-mile (69 km) long stream located in Cuyahoga and Lake counties in the state of Ohio in the United States. The 11.5-mile (18.5 km) long main branch runs from the Euclid Creek Reservation of the Cleveland Metroparks to Lake Erie. The west branch is usually considered part of the main branch, and extends another 16 miles (26 km) to the creek's headwaters in Beachwood, Ohio. The east branch runs for 19 miles (31 km) and has headwaters in Willoughby Hills, Ohio.