The Alien and Sedition Acts were a set of four laws enacted in 1798 that applied restrictions to immigration and speech in the United States. The Naturalization Act increased the requirements to seek citizenship, the Alien Friends Act allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens, the Alien Enemies Act gave the president additional powers to detain non-citizens during times of war, and the Sedition Act criminalized false and malicious statements about the federal government. The Alien Friends Act and the Sedition Act expired after a set number of years, and the Naturalization Act was repealed in 1802. The Alien Enemies Act is still in effect.

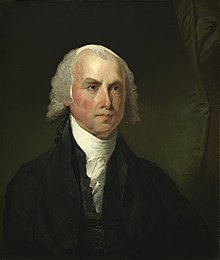

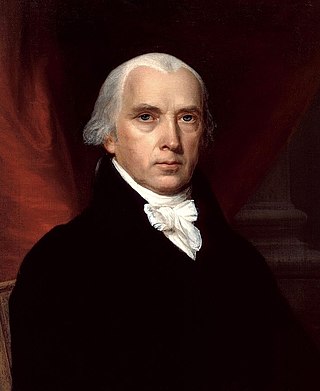

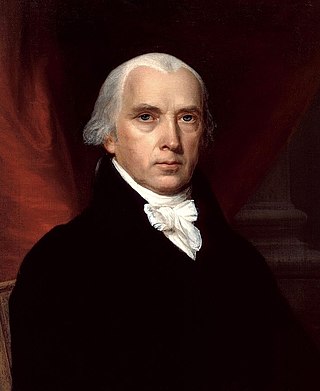

James Madison Jr. was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued that the states had the right and the duty to declare unconstitutional those acts of Congress that the Constitution did not authorize. In doing so, they argued for states' rights and strict construction of the Constitution. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 were written secretly by Vice President Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, respectively.

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s that championed republicanism, individual liberty, equal rights, decentralization, free markets, free trade, agrarianism, and sympathy with the French Revolution. The party became increasingly dominant after the 1800 elections as the opposing Federalist Party collapsed.

The Federalist Party was a conservative and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. Under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801. Defeated by the Democratic-Republican Party in 1800, it became a minority party while keeping its stronghold in New England and made a brief resurgence by opposing the War of 1812. It then collapsed with its last presidential candidate in 1816. Remnants lasted for a few years afterwards. The party appealed to businesses and to conservatives who favored banks, national over state government, manufacturing, an army and navy, and in world affairs preferred Great Britain and strongly opposed the French Revolution. The party favored centralization, federalism, modernization, industrialization, and protectionism.

The 1800 United States presidential election was the fourth quadrennial presidential election. It was held from October 31 to December 3, 1800. In what is sometimes called the "Revolution of 1800", the Democratic-Republican Party candidate, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, defeated the Federalist Party candidate, incumbent president John Adams. The election was a political realignment that ushered in a generation of Democratic-Republican leadership. This was the first rematch in American history.

John Breckinridge was a lawyer, slave-owning planter, soldier, and politician in the U.S. states of Virginia and Kentucky. He served several terms each in the state legislatures of Virginia and Kentucky before legislators elected him to the U.S. Senate. He also served as United States Attorney General during the second term of President Thomas Jefferson. He is the progenitor of Kentucky's Breckinridge political family and the namesake of Breckinridge County, Kentucky.

The 5th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from March 4, 1797, to March 4, 1799, during the first two years of John Adams' presidency. In the context of the Quasi-War with France, the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed by Congress. The Acts were overwhelmingly supported by the Federalists and mostly opposed by the Democratic-Republicans. Some Democratic-Republicans, such as Timothy Bloodworth, said they would support formally going to war against France but they opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts which Bloodworth and others believed were unconstitutional.

The nullification crisis was a sectional political crisis in the United States in 1832 and 1833, during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, which involved a confrontation between the state of South Carolina and the federal government. It ensued after South Carolina declared the federal Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the sovereign boundaries of the state. However, courts at the state and federal level, including the U.S. Supreme Court, repeatedly have rejected the theory of nullification by states.

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the Tenth Amendment. The enumerated powers that are listed in the Constitution include exclusive federal powers, as well as concurrent powers that are shared with the states, and all of those powers are contrasted with the reserved powers—also called states' rights—that only the states possess.

William Branch Giles was an American statesman, long-term Senator from Virginia, and the 24th Governor of Virginia. He served in the House of Representatives from 1790 to 1798 and again from 1801 to 1803; in between, he was a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and was an Elector for Jefferson in 1800. He served as a United States Senator from 1804 to 1815 and then served briefly in the House of Delegates again. After a time in private life, he joined the opposition to John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay in 1824; he ran for the Senate again in 1825 and was defeated but appointed Governor for three one-year terms in 1827; he was succeeded by John Floyd, in the year of his death.

The Hartford Convention was a series of meetings from December 15, 1814, to January 5, 1815, in Hartford, Connecticut, United States, in which the New England Federalist Party met to discuss their grievances concerning the ongoing War of 1812 and the political problems arising from the federal government's increasing power.

The Midnight Judges Act represented an effort to solve an issue in the U.S. Supreme Court during the early 19th century. There was concern, beginning in 1789, about the system that required the Justices of the Supreme Court to "ride circuit" and reiterate decisions made in the appellate level courts. The Supreme Court Justices had often expressed concern and suggested that the judges of the Supreme and circuit courts be divided. The Act was repealed by Congress on January 22, 1802.

Interposition is a claimed right of a U.S. state to oppose actions of the federal government that the state deems unconstitutional. Under the theory of interposition, a state assumes the right to "interpose" itself between the federal government and the people of the state by taking action to prevent the federal government from enforcing laws that the state considers unconstitutional.

In the United States, judicial review is the legal power of a court to determine if a statute, treaty, or administrative regulation contradicts or violates the provisions of existing law, a State Constitution, or ultimately the United States Constitution. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly define the power of judicial review, the authority for judicial review in the United States has been inferred from the structure, provisions, and history of the Constitution.

The presidency of John Adams, began on March 4, 1797, when John Adams was inaugurated as the second president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1801. Adams, who had served as vice president under George Washington, took office as president after winning the 1796 presidential election. The only member of the Federalist Party to ever serve as president, his presidency ended after a single term following his defeat in the 1800 presidential election. He was succeeded by Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Nullification, in United States constitutional history, is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal laws which they deem unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution. There are similar theories that any officer, jury, or individual may do the same. The theory of state nullification has never been legally upheld by federal courts, although jury nullification has.

The Federalist Era in American history ran from 1788 to 1800, a time when the Federalist Party and its predecessors were dominant in American politics. During this period, Federalists generally controlled Congress and enjoyed the support of President George Washington and President John Adams. The era saw the creation of a new, stronger federal government under the United States Constitution, a deepening of support for nationalism, and diminished fears of tyranny by a central government. The era began with the ratification of the United States Constitution and ended with the Democratic-Republican Party's victory in the 1800 elections.

In the context of the United States, secession primarily refers to the voluntary withdrawal of one or more states from the Union that constitutes the United States; but may loosely refer to leaving a state or territory to form a separate territory or new state, or to the severing of an area from a city or county within a state. Advocates for secession are called disunionists by their contemporaries in various historical documents.

The Principles of '98 refer to the American political position after 1798 that individual states could both judge the constitutionality of federal laws and decrees and refuse to enforce those that were deemed unconstitutional. That refusal is generally referred to as "nullification" but has also been expressed as "interposition:" the states' right to "interpose" between the federal government and the people of the state.