A security is a tradable financial asset. The term commonly refers to any form of financial instrument, but its legal definition varies by jurisdiction. In some countries and languages people commonly use the term "security" to refer to any form of financial instrument, even though the underlying legal and regulatory regime may not have such a broad definition. In some jurisdictions the term specifically excludes financial instruments other than equity and fixed income instruments. In some jurisdictions it includes some instruments that are close to equities and fixed income, e.g., equity warrants.

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress on February 25, 1791. It followed the Bank of North America, the nation's first de facto national bank. However, neither served the functions of a modern central bank: They did not set monetary policy, regulate private banks, hold their excess reserves, or act as a lender of last resort. They were national insofar as they were allowed to have branches in multiple states and lend money to the US government. Other banks in the US were each chartered by, and only allowed to have branches in, a single state.

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money borrowed or otherwise withheld from another party, the creditor. Debt may be owed by a sovereign state or country, local government, company, or an individual. Commercial debt is generally subject to contractual terms regarding the amount and timing of repayments of principal and interest. Loans, bonds, notes, and mortgages are all types of debt. In financial accounting, debt is a type of financial transaction, as distinct from equity.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a United States government corporation supplying deposit insurance to depositors in American commercial banks and savings banks. The FDIC was created by the Banking Act of 1933, enacted during the Great Depression to restore trust in the American banking system. More than one-third of banks failed in the years before the FDIC's creation, and bank runs were common. The insurance limit was initially US$2,500 per ownership category, and this has been increased several times over the years. Since the enactment of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, the FDIC insures deposits in member banks up to $250,000 per ownership category. FDIC insurance is backed by the full faith and credit of the government of the United States, and according to the FDIC, "since its start in 1933 no depositor has ever lost a penny of FDIC-insured funds".

The Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund are trust funds that provide for payment of Social Security benefits administered by the United States Social Security Administration.

Robert Morris Jr. was an English-born American merchant, investor and politician who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He served as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature, the Second Continental Congress, and the United States Senate, and he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution. From 1781 to 1784, he served as the Superintendent of Finance of the United States, becoming known as the "Financier of the Revolution." Along with Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin, he is widely regarded as one of the founders of the financial system of the United States.

Fractional-reserve banking is the system of banking in all countries worldwide, under which banks that take deposits from the public keep only part of their deposit liabilities in liquid assets as a reserve, typically lending the remainder to borrowers. Bank reserves are held as cash in the bank or as balances in the bank's account at the central bank. Fractional-reserve banking differs from the hypothetical alternative model, full-reserve banking, in which banks would keep all depositor funds on hand as reserves.

A sinking fund is a fund established by an economic entity by setting aside revenue over a period of time to fund a future capital expense, or repayment of a long-term debt.

A Demand Note is a type of United States paper money that was issued from August 1861 to April 1862 during the American Civil War in denominations of 5, 10, and 20 US$. Demand Notes were the first issue of paper money by the United States that achieved wide circulation. The U.S. government placed Demand Notes into circulation by using them to pay expenses incurred during the Civil War including the salaries of its workers and military personnel.

A vulture fund is a hedge fund, private-equity fund or distressed debt fund, that invests in debt considered to be very weak or in default, known as distressed securities. Investors in the fund profit by buying debt at a discounted price on a secondary market and then using numerous methods to subsequently sell the debt for a larger amount than the purchasing price. Debtors include companies, countries, and individuals.

The First Report on the Public Credit was one of four major reports on fiscal and economic policy submitted by Founding Father and first US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton on the request of Congress. The report analyzed the financial standing of the United States and made recommendations to reorganize the national debt and to establish the public credit. Commissioned by the US House of Representatives on September 21, 1789, the report was presented on January 9, 1790, at the second session of the 1st US Congress.

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage, in civil law jurisdictions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any purpose while putting a lien on the property being mortgaged. The loan is "secured" on the borrower's property through a process known as mortgage origination. This means that a legal mechanism is put into place which allows the lender to take possession and sell the secured property to pay off the loan in the event the borrower defaults on the loan or otherwise fails to abide by its terms. The word mortgage is derived from a Law French term used in Britain in the Middle Ages meaning "death pledge" and refers to the pledge ending (dying) when either the obligation is fulfilled or the property is taken through foreclosure. A mortgage can also be described as "a borrower giving consideration in the form of a collateral for a benefit (loan)".

In United States history, the Second Report on the Public Credit, also referred to as The Report on a National Bank, was the second of four influential reports on fiscal and economic policy delivered to Congress by the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Submitted on December 14, 1790, the report called for the establishment of a central bank with the primary purpose to expand the flow of legal tender, monetizing the national debt by issuing of federal bank notes.

The state Bank of Indiana was a government chartered banking institution established in 1833 in response to the state's shortage of capital caused by the closure of the Second Bank of the United States by the administration of President Andrew Jackson. The bank operated for twenty-six years and allowed the state to finance its internal improvements, stabilized the state's currency problems, and encouraged greater private economic growth. The bank closed in 1859. The profits were then split between the shareholders, allowing depositors to exchange their bank notes for federal notes, and the bank's buildings and infrastructure were sold and reincorporated as the privately owned Second Bank of Indiana.

The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) is a program of the United States government to purchase toxic assets and equity from financial institutions to strengthen its financial sector that was passed by Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush. It was a component of the government's measures in 2009 to address the subprime mortgage crisis.

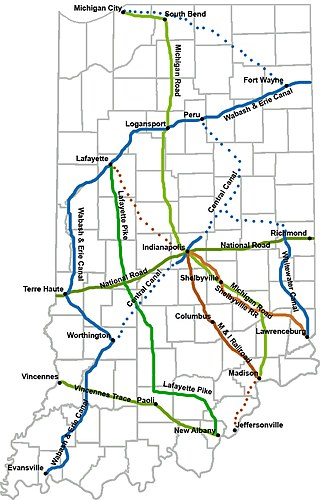

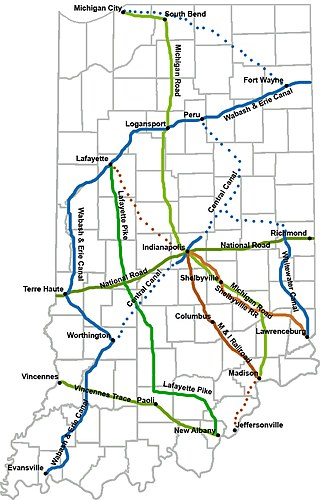

The Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act was a law passed by the Indiana General Assembly and signed by Whig Governor Noah Noble in 1836 that greatly expanded the state's program of internal improvements. It added $10 million to spending and funded several projects, including turnpikes, canals, and later, railroads. The following year the state economy was adversely affected by the Panic of 1837 and the overall project ended in a near total disaster for the state, which narrowly avoided total bankruptcy from the debt.

The Panic of 1792 was a financial credit crisis that occurred during the months of March and April 1792, precipitated by the expansion of credit by the newly formed Bank of the United States as well as by rampant speculation on the part of William Duer, Alexander Macomb, and other prominent bankers. Duer, Macomb, and their colleagues attempted to drive up prices of United States (U.S) debt securities and bank stocks, but when they defaulted on loans, prices fell, causing a bank run. Simultaneous tightening of credit by the Bank of the United States served to heighten the initial panic. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton was able to deftly manage the crisis by providing banks across the Northeast United States with hundreds of thousands of dollars to make open-market purchases of securities, which allowed the market to stabilize by May 1792.

A Treasury Note is a type of short term debt instrument issued by the United States prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Without the alternatives offered by a federal paper money or a central bank, the U.S. government relied on these instruments for funding during periods of financial stress such as the War of 1812, the Panic of 1837, and the American Civil War. While the Treasury Notes, as issued, were neither legal tender nor representative money, some issues were used as money in lieu of an official federal paper money. However the motivation behind their issuance was always funding federal expenditures rather than the provision of a circulating medium. These notes typically were hand-signed, of large denomination, of large dimension, bore interest, were payable to the order of the owner, and matured in no more than three years – though some issues lacked one or more of these properties. Often they were receivable at face value by the government in payment of taxes and for purchases of publicly owned land, and thus "might to some extent be regarded as paper money." On many issues the interest rate was chosen to make interest calculations particularly easy, paying either 1, 1+1⁄2, or 2 cents per day on a $100 note.

The Funding Act of 1790, the full title of which is An Act making provision for the [payment of the] Debt of the United States, was passed on August 4, 1790, by the United States Congress as part of the Compromise of 1790, to address the issue of funding of the domestic debt incurred by the state governments, first as Thirteen Colonies, then as states in rebellion, in independence, in Confederation, and finally as members of a single federal Union. By the Act, the newly-inaugurated federal government under the U.S. Constitution assumed and thereby retired the debts of each of the individual colonies in rebellion and the bonded debts of the States in Confederation, which each state had individually and independently issued on its own "full faith and credit" when each of them was, in effect, an independent nation.

The Bank Bill of 1791 is a common term for two bills passed by the First Congress of the United States of America on February 25 and March 2 of 1791.