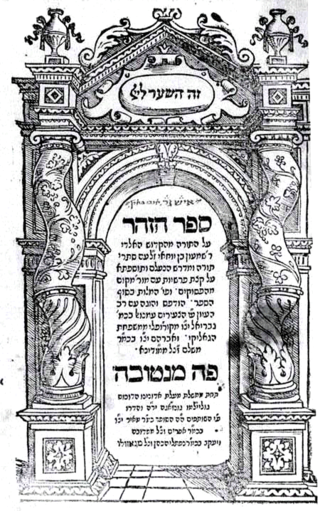

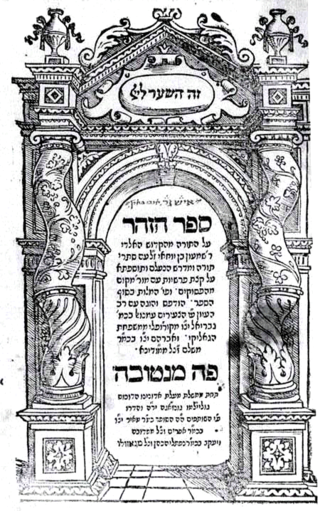

The Zohar is a foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah originally written in Aramaic. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology. The Zohar contains discussions of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and "true self" to "The Light of God".

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writing, and thus corresponds with the Hebrew term Sifrut Chazal. This more specific sense of "Rabbinic literature"—referring to the Talmudim, Midrash, and related writings, but hardly ever to later texts—is how the term is generally intended when used in contemporary academic writing. The terms mefareshim and parshanim (commentaries/commentators) almost always refer to later, post-Talmudic writers of rabbinic glosses on Biblical and Talmudic texts.

Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, also known by the Hebrew acronym RaMCHaL, was a prominent Italian Jewish rabbi, kabbalist, and philosopher.

Tzadik is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d-q, which means "justice" or "righteousness". When applied to a righteous woman, the term is inflected as tzadika/tzaddikot.

Hoshana Rabbah is the seventh day of the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, the 21st day of the month of Tishrei. This day is marked by a special synagogue service, the Hoshana Rabbah, in which seven circuits are made by the worshippers with their lulav and etrog, while the congregation recites Hoshanot. It is customary for the scrolls of the Torah to be removed from the ark during this procession. In a few communities a shofar is sounded after each circuit.

Lech-Lecha, Lekh-Lekha, or Lech-L'cha is the third weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It constitutes Genesis 12:1–17:27. The parashah tells the stories of God's calling of Abram, Abram's passing off his wife Sarai as his sister, Abram's dividing the land with his nephew Lot, the war between the four kings and the five, the covenant between the pieces, Sarai's tensions with her maid Hagar and Hagar's son Ishmael, and the covenant of circumcision.

Noach, Noiach, Nauach, Nauah, or Noah is the second weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It constitutes Genesis 6:9–11:32. The parashah tells the stories of the Flood and Noah's Ark, of Noah's subsequent drunkenness and cursing of Canaan, and of the Tower of Babel.

The priesthood of Melchizedek is a role in Abrahamic religions, modelled on Melchizedek, combining the dual position of king and priest.

Isaiah 53 is the fifty-third chapter of the Book of Isaiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains the prophecies attributed to the prophet Isaiah and is one of the Nevi'im. Chapters 40 to 55 are known as "Deutero-Isaiah" and date from the time of the Israelites' exile in Babylon.

In Jewish eschatology Mashiach ben Yoseph or Messiah ben Joseph, also known as Mashiach bar/ben Ephraim, is a Jewish messiah from the tribe of Ephraim and a descendant of Joseph. The figure's origins are much debated. Some regard it as a rabbinic invention, but others defend the view that its origins are in the Torah.

In the Bible, Melchizedek, also transliterated Melchisedech or Malki Tzedek, was the king of Salem and priest of El Elyon. He is first mentioned in Genesis 14:18–20, where he brings out bread and wine and then blesses Abram and El Elyon.

Elijah Benamozegh, sometimes Elia or Eliyahu, was an Italian Sephardic Orthodox rabbi and renowned Jewish Kabbalist, highly respected in his day as one of Italy's most eminent Jewish scholars. He served for half a century as rabbi of the important Jewish community of Livorno, where the "Piazza Benamozegh" now commemorates his name and distinction. His major work is Israel and Humanity (1863), which was translated into English by Dr. Mordechai Luria in 1995.

Practical Kabbalah in historical Judaism, is a branch of the Jewish mystical tradition that concerns the use of magic. It was considered permitted white magic by its practitioners, reserved for the elite, who could separate its spiritual source from Qliphoth realms of evil if performed under circumstances that were holy (Q-D-Š) and pure, tumah and taharah. The concern of overstepping Judaism's strong prohibitions of impure magic ensured it remained a minor tradition in Jewish history. Its teachings include the use of Divine and angelic names for amulets and incantations.

Sifrei Kodesh, commonly referred to as sefarim, or in its singular form, sefer, are books of Jewish religious literature and are viewed by religious Jews as sacred. These are generally works of Torah literature, i.e. Tanakh and all works that expound on it, including the Mishnah, Midrash, Talmud, and all works of halakha, Musar, Hasidism, Kabbalah, or machshavah. Historically, sifrei kodesh were generally written in Hebrew with some in Judeo-Aramaic or Arabic, although in recent years, thousands of titles in other languages, most notably English, were published. An alternative spelling for 'sefarim' is seforim.

Various numbers play a significant role in Jewish texts or practice. Some such numbers were used as mnemonics to help remember concepts, while other numbers were considered to have intrinsic significance or allusive meaning.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Judaism:

According to Judaism, the priestly covenant is the biblical covenant that God gave to Aaron and his descendants, the kohanim. This covenant consisted of their exclusive right to serve in the Temple, and to consume sacrificial offerings and receive other priestly gifts.

A bat-kohen or bat kohen is the daughter of a kohen, who holds a special status in the Hebrew Bible and rabbinical texts. She is entitled to a number of rights and is encouraged to abide by specified requirements, for example, entitlement to consume some of the priestly gifts, and an increased value for her ketubah.

A Baal Shem was a historical Jewish practitioner of Practical Kabbalah and supposed miracle worker. Employing the names of God, angels, Satan and other spirits, Baalei Shem are claimed to heal, enact miracles, perform exorcisms, treat various health issues, curb epidemics, protect people from disaster due to fire, robbery or the evil eye, foresee the future, decipher dreams, and bless those who sought his powers.

Isaac ben Melchizedek, was a rabbinic scholar from Siponto, Italy, and one of the first medieval scholars to have composed a commentary on the Mishnah, of which only his commentary on Seder Zera'im survives. Elements of the Mishnaic order of Taharot are also cited in his name by the Tosafists, but the complete work is no longer extant.