Related Research Articles

A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term. Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions, and extensional definitions. Another important category of definitions is the class of ostensive definitions, which convey the meaning of a term by pointing out examples. A term may have many different senses and multiple meanings, and thus require multiple definitions.

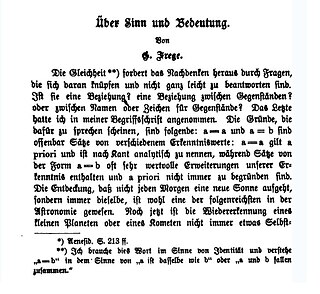

In the philosophy of language, a proper name – examples include a name of a specific person or place – is a name which ordinarily is taken to uniquely identify its referent in the world. As such it presents particular challenges for theories of meaning, and it has become a central problem in analytic philosophy. The common-sense view was originally formulated by John Stuart Mill in A System of Logic (1843), where he defines it as "a word that answers the purpose of showing what thing it is that we are talking about but not of telling anything about it". This view was criticized when philosophers applied principles of formal logic to linguistic propositions. Gottlob Frege pointed out that proper names may apply to imaginary and nonexistent entities, without becoming meaningless, and he showed that sometimes more than one proper name may identify the same entity without having the same sense, so that the phrase "Homer believed the morning star was the evening star" could be meaningful and not tautological in spite of the fact that the morning star and the evening star identifies the same referent. This example became known as Frege's puzzle and is a central issue in the theory of proper names.

Saul Aaron Kripke was an American analytic philosopher and logician. He was Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and emeritus professor at Princeton University. Kripke is considered one of the most important philosophers of the latter half of the 20th century. Since the 1960s, he has been a central figure in a number of fields related to mathematical and modal logic, philosophy of language and mathematics, metaphysics, epistemology, and recursion theory.

In the philosophy of language, the distinction between sense and reference was an idea of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottlob Frege in 1892, reflecting the two ways he believed a singular term may have meaning.

In metaphysics and the philosophy of language, an empty name is a proper name that has no referent.

David John Chalmers is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist specializing in the areas of philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well as co-director of NYU's Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness. In 2006, he was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2013, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

Ruth Barcan Marcus was an American academic philosopher and logician best known for her work in modal and philosophical logic. She developed the first formal systems of quantified modal logic and in so doing introduced the schema or principle known as the Barcan formula. Marcus, who originally published as Ruth C. Barcan, was, as Don Garrett notes "one of the twentieth century's most important and influential philosopher-logicians". Timothy Williamson, in a 2008 celebration of Marcus' long career, states that many of her "main ideas are not just original, and clever, and beautiful, and fascinating, and influential, and way ahead of their time, but actually – I believe – true".

A causal theory of reference or historical chain theory of reference is a theory of how terms acquire specific referents based on evidence. Such theories have been used to describe many referring terms, particularly logical terms, proper names, and natural kind terms. In the case of names, for example, a causal theory of reference typically involves the following claims:

The open-question argument is a philosophical argument put forward by British philosopher G. E. Moore in §13 of Principia Ethica (1903), to refute the equating of the property of goodness with some non-moral property, X, whether natural or supernatural. That is, Moore's argument attempts to show that no moral property is identical to a natural property. The argument takes the form of a syllogism modus tollens:

In the philosophy of language and modal logic, a term is said to be a non-rigid designator or connotative term if it does not extensionally designate the same object in all possible worlds. This is in contrast to a rigid designator, which does designate the same object in all possible worlds in which that object exists, and does not designate anything else in those worlds in which that object does not exist. The term was coined by Saul Kripke in his 1970 lecture series at Princeton University, later published as the book Naming and Necessity.

A direct reference theory is a theory of language that claims that the meaning of a word or expression lies in what it points out in the world. The object denoted by a word is called its referent. Criticisms of this position are often associated with Ludwig Wittgenstein.

A sign relation is the basic construct in the theory of signs, also known as semiotics, as developed by Charles Sanders Peirce.

In the philosophy of language, the descriptivist theory of proper names is the view that the meaning or semantic content of a proper name is identical to the descriptions associated with it by speakers, while their referents are determined to be the objects that satisfy these descriptions. Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege have both been associated with the descriptivist theory, which is sometimes called the mediated reference theory or Frege–Russell view.

Keith Sedgwick Donnellan was an American philosopher and professor of philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles.

A priori and a posteriori are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. A priori knowledge is independent from any experience. Examples include mathematics, tautologies, and deduction from pure reason. A posteriori knowledge depends on empirical evidence. Examples include most fields of science and aspects of personal knowledge.

Naming and Necessity is a 1980 book with the transcript of three lectures, given by the philosopher Saul Kripke, at Princeton University in 1970, in which he dealt with the debates of proper names in the philosophy of language. The transcript was brought out originally in 1972 in Semantics of Natural Language, edited by Donald Davidson and Gilbert Harman. Among analytic philosophers, Naming and Necessity is widely considered one of the most important philosophical works of the twentieth century.

Two-dimensionalism is an approach to semantics in analytic philosophy. It is a theory of how to determine the sense and reference of a word and the truth-value of a sentence. It is intended to resolve the puzzle: How is it possible to discover empirically that a necessary truth is true? Two-dimensionalism provides an analysis of the semantics of words and sentences that makes sense of this possibility. The theory was first developed by Robert Stalnaker, but it has been advocated by numerous philosophers since, including David Chalmers.

In philosophy, specifically in the area of metaphysics, counterpart theory is an alternative to standard (Kripkean) possible-worlds semantics for interpreting quantified modal logic. Counterpart theory still presupposes possible worlds, but differs in certain important respects from the Kripkean view. The form of the theory most commonly cited was developed by David Lewis, first in a paper and later in his book On the Plurality of Worlds.

A posteriori necessity is a thesis in metaphysics and the philosophy of language, that some statements of which we must acquire knowledge a posteriori are also necessarily true. It challenges previously widespread belief that only a priori knowledge can be necessary. It draws on a number of philosophical concepts such as necessity, the causal theory of reference, rigidity, and the a priori–a posteriori distinction.

In modal logic, the necessity of identity is the thesis that for every object x and object y, if x and y are the same object, it is necessary that x and y are the same object. The thesis is best known for its association with Saul Kripke, who published it in 1971, although it was first derived by the logician Ruth Barcan Marcus in 1947, and later, in simplified form, by W. V. O. Quine in 1953.