The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the A.M.E. Church or AME, is a predominantly African-American Methodist denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal Church is the first independent Protestant denomination to be founded by black people, though it welcomes and has members of all ethnicities. It was founded by the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816 from several black Methodist congregations in the mid-Atlantic area who wanted to escape the discrimination that was commonplace in society. It was among the first denominations in the United States to be founded for this reason, rather than for theological distinctions, and has persistently advocated for the civil and human rights of African Americans through social improvement, religious autonomy, and political engagement, while always being open to people of all racial backgrounds. Allen, a deacon in the Methodist Episcopal Church, was consecrated its first bishop in 1816 by a conference of five churches from Philadelphia to Baltimore. The denomination then expanded west and south, particularly after the Civil War. By 1906, the AME had a membership of about 500,000, more than the combined total of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in America and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, making it the largest major African-American Methodist denomination.

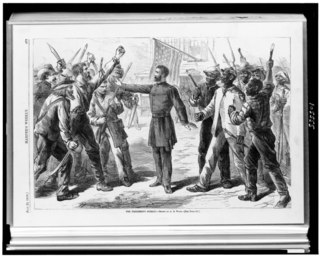

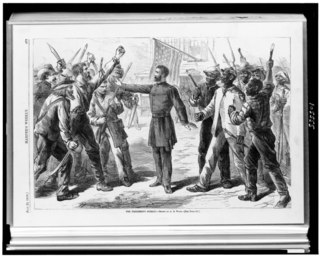

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an important agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a U.S. government agency, from 1865 to 1872, after the American Civil War, to direct "provisions, clothing, and fuel...for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children".

Mount Olivet Cemetery is a 206-acre (83 ha) cemetery located in Nashville, Tennessee. It is located approximately two miles East of downtown Nashville, and adjacent to the Catholic Calvary Cemetery. It is open to the public during daylight hours.

Thomas A. Kercheval was a Republican Tennessee Senator and the Mayor of Nashville for twelve years.

Sarah Jane Woodson Early, born Sarah Jane Woodson, was an American educator, black nationalist, temperance activist and author. A graduate of Oberlin College, where she majored in classics, she was hired at Wilberforce University in 1858 as the first black woman college instructor, and also the first black American to teach at a historically black college or university (HBCU).

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life." Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the Thirteen Colonies. The Methodist and Baptist churches became much more active in the 1780s. Their growth was quite rapid for the next 150 years, until their membership included the majority of black Americans.

Benjamin Franklin Whittemore, also known as B. F. Whittemore, was a minister, politician, and publisher. After his theological studies, he was a minister and then during the Civil War, a chaplain for Massachusetts regiments. Stationed in South Carolina at the end of the war, he accepted a position of superintendent of education for the Freedmen's Bureau. He was a Republican U.S. Representative from South Carolina. He was censured in 1870 for selling appointments to the United States Naval Academy and other military academies. He spent his later years in Massachusetts, where he was a publisher.

Erastus Milo Cravath (1833–1900) was a pastor and American Missionary Association (AMA) official who after the American Civil War, helped found Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and numerous other historically black colleges in Georgia and Tennessee for the education of freedmen. He also served as president of Fisk University for more than 20 years.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Henry McNeal Turner was a minister, politician, and the 12th elected and consecrated bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). After the American Civil War, he worked to establish new A.M.E. congregations among African Americans in Georgia. Born free in South Carolina, Turner learned to read and write and became a Methodist preacher. He joined the AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1858, where he became a minister. Founded by free blacks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the early 19th century, the A.M.E. Church was the first independent black denomination in the United States. Later Turner had pastorates in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC.

John Angelo Lester was an American educator, physician and administrator in Nashville, Tennessee between 1895 and 1934. He was a professor of physiology at Meharry Medical College and was named Professor Emeritus in 1930. Lester served as an executive officer in the National Medical Association and various state and regional medical associations throughout Tennessee, a mecca for Negro physicians since Reconstruction.

Thomas H. Malone (1834-1906) was an American Confederate veteran, judge, businessman and academic administrator. He served as the President of the Nashville Gas Company from 1893 to 1906. He served as the second Dean of the Vanderbilt University Law School from 1875 to 1904.

For the Missouri politician, see Robert A. Young.

Donald W. Southgate (1887–1953) was an American architect. He designed many buildings in Davidson County, Tennessee, especially Nashville and Belle Meade, some of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Edward Bushrod Stahlman was a German-born American railroad executive, newspaper publisher and real estate investor. He was the vice president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and the Louisville, New Albany and Chicago Railroad. He built The Stahlman, a skyscraper in Nashville, Tennessee, and he was the publisher of the Nashville Banner for 44 years.

Joseph Thorpe Elliston was an American silversmith, planter and politician. He served as the fourth mayor of Nashville, Tennessee from 1814 to 1817. He owned land in mid-town Nashville, on parts of modern-day Centennial Park, Vanderbilt University, and adjacent West End Park.

Elias Polk was a former enslaved African American, most known for being enslaved by President James K. Polk and his family from the time of his birth until emancipation in 1865. After the American Civil War, he became a conservative Democratic political activist, when most freedmen allied with the Republican Party. As a person enslaved, Polk had lived and worked at the Polk farm in Maury County, Tennessee, in the Columbia, Tennessee home of James and Sarah Polk, in the White House in 1845, and the Polks' Nashville residence, "Polk Place" from 1849-1865. After the president died, Elias Polk continued to live at Polk Place in Nashville, where he continued to be enslaved by the widowed First Lady Sarah Childress Polk. Once Elias gained freedom, he embarked on a public speaking career which saw him take up the cause of the Democratic Party, and spoke on behalf of former Confederates and enslavers. This was done out of survival and economic stability. Elias is remembered today for his controversial stances and willingness to "play the part" of the faithful slave in order to subvert and mock the southern racial hierarchy to his advantage.

Harriet McClintock Marshall was a conductor on the Underground Railroad whose home in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania served as a stop or safe house for the clandestine network, along with the Wesley Union African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and other homes in the city. She offered shelter, food, and clothing to people escaping slavery. Her husband Elisha Marshall, a formerly enslaved man and veteran of the American Civil War, was also active in helping people reach freedom, often providing transportation.

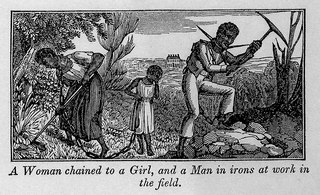

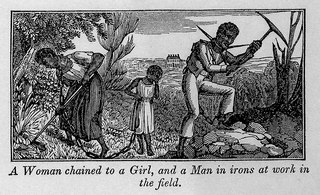

Marriage of enslaved people in the United States was generally not legal prior to the Civil War (1861–1865). African-Americans were considered chattel legally, and they were denied human or civil rights until slavery was abolished after the Civil War and with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Both state and federal laws denied, or rarely defined, rights to enslaved people.

The Colored American published in Augusta, Georgia from October 1865 to February 1866. It was the first African American newspaper in the South. The paper was founded by John T. Shuften, who was forced to sell the paper within six months due to a lack of financial support. The paper was published by John T. Shapiro. The Colored American covered political, religious, and general news. Shuften published the newspaper with assistance from James D. Lynch. The paper was purchased in January 1866 by the Georgia Equal Rights Association, and the name was changed to the Loyal Georgian, published by John Emory Bryant.