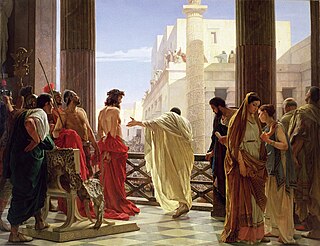

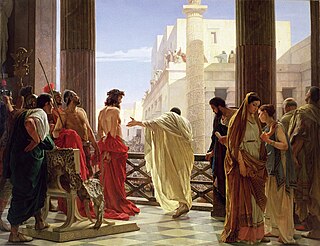

Pontius Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of Jesus and ultimately ordered his crucifixion. Pilate's importance in Christianity is underscored by his prominent place in both the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds. Because the gospels portray Pilate as reluctant to execute Jesus, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church believes that Pilate became a Christian and venerates him as both a martyr and a saint, a belief which is historically shared by the Coptic Church, with a feast day on 19 or 25 June, respectively.

Early Christian art and architecture is the art produced by Christians, or under Christian patronage, from the earliest period of Christianity to, depending on the definition, sometime between 260 and 525. In practice, identifiably Christian art only survives from the 2nd century onwards. After 550, Christian art is classified as Byzantine, or according to region.

The art of Ancient Rome, and the territories of its Republic and later Empire, includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be minor forms of Roman art, although they were not considered as such at the time. Sculpture was perhaps considered as the highest form of art by Romans, but figure painting was also highly regarded. A very large body of sculpture has survived from about the 1st century BC onward, though very little from before, but very little painting remains, and probably nothing that a contemporary would have considered to be of the highest quality.

The St Augustine Gospels is an illuminated Gospel Book which dates from the 6th century and has been in the Parker Library in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge since 1575. It was made in Italy and has been in England since fairly soon after its creation; by the 16th century it had probably already been at Canterbury for almost a thousand years. It has 265 leaves measuring about 252 x 196 mm, and is not entirely complete, in particular missing pages with miniatures.

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to Greek sculpture. Many examples of even the most famous Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and Barberini Faun, are known only from Roman Imperial or Hellenistic "copies". At one time, this imitation was taken by art historians as indicating a narrowness of the Roman artistic imagination, but, in the late 20th century, Roman art began to be reevaluated on its own terms: some impressions of the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be based on Roman artistry.

The Good Shepherd is an image used in the pericope of John 10:1–21, in which Jesus Christ is depicted as the Good Shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep. Similar imagery is used in Psalm 23 and Ezekiel 34:11–16. The Good Shepherd is also discussed in the other gospels, the Epistle to the Hebrews, the First Epistle of Peter and the Book of Revelation.

Santa Costanza is a 4th-century church in Rome, Italy, on the Via Nomentana, which runs north-east out of the city. It is a round building with well preserved original layout and mosaics. It has been built adjacent to a horseshoe-shaped church, now in ruins, which has been identified as the initial 4th-century cemeterial basilica of Saint Agnes. Santa Costanza and the old Saint Agnes were both constructed over the earlier catacombs in which Saint Agnes is believed to be buried.

In ancient Greek religion, kriophoros or criophorus, the "ram-bearer," is a figure of Hermes that commemorates the solemn sacrifice of a ram; thus, one of the god's epithets is Hermes Kriophoros.

Christ in Majesty or Christ in Glory is the Western Christian image of Christ seated on a throne as ruler of the world, always seen frontally in the centre of the composition, and often flanked by other sacred figures, whose membership changes over time and according to the context. The image develops from Early Christian art, as a depiction of the Heavenly throne as described in 1 Enoch, Daniel 7, and The Apocalypse of John. In the Byzantine world, the image developed slightly differently into the half-length Christ Pantocrator, "Christ, Ruler of All", a usually unaccompanied figure, and the Deesis, where a full-length enthroned Christ is entreated by Mary and St. John the Baptist, and often other figures. In the West, the evolving composition remains very consistent within each period until the Renaissance, and then remains important until the end of the Baroque, in which the image is ordinarily transported to the sky.

Berzé-la-Ville is a commune in the Saône-et-Loire department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

The Flagellation of Christ, in art sometimes known as Christ at the Column or the Scourging at the Pillar, is an episode from the Passion of Jesus as presented in the Gospels. As such, it is frequently shown in Christian art, in cycles of the Passion or the larger subject of the Life of Christ. Catholic tradition places the Flagellation on the site of the Church of the Flagellation (the second station of the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. It is the second Sorrowful Mystery of the Rosary and the sixth station of the John Paul II’s Scriptural Way of the Cross. The column to which Christ is normally shown to be tied, and the rope, scourge, whip or birch are elements in the Arma Christi. The Basilica di Santa Prassede in Rome is one of the churches claiming to possess the original column or parts of it.

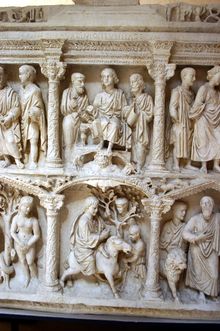

Early Christian sarcophagi are those Ancient Roman sarcophagi carrying inscriptions or carving relating them to early Christianity. They were produced from the late 3rd century through to the 5th century. They represent the earliest form of large Christian sculpture, and are important for the study of Early Christian art.

Junius Bassus was a praetorian prefect of the Roman Empire from 318 to 331, during which time he also held the consulate. Several laws in the Codex Theodosianus are addressed to him. His son Junius Bassus Theotecnius was praefectus urbi, and his sarcophagus from 359 is one of the most decorative late antique sarcophagi adorned with two registers of Christian scenes.

The Dogmatic Sarcophagus, also known as the "Trinity Sarcophagus" is an early Christian sarcophagus dating to 320–350, now in the Vatican Museums. It was discovered in the 19th century during rebuilding works at the basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura, in Rome, Italy.

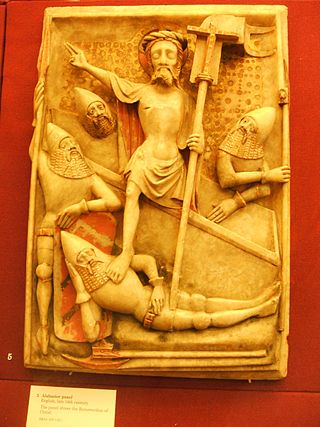

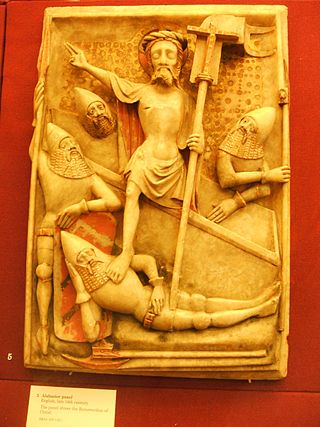

The resurrection of Jesus has long been central to Christian faith and Christian art, whether as a single scene or as part of a cycle of the Life of Christ. In the teachings of the traditional Christian churches, the sacraments derive their saving power from the passion and resurrection of Christ, upon which the salvation of the world entirely depends. The redemptive value of the resurrection has been expressed through Christian art, as well as being expressed in theological writings.

The Twelve Apostles are a common subject in Christian art and serve as a devotional tool for many Christian denominations. They were instrumental in teaching the gospel of Jesus, "continuing the mission of Jesus" with their depictions continuing to serve as spiritual inspiration and authority. Many Protestant denominations reject religious imagery, including the veneration of the apostles and other religious figures.

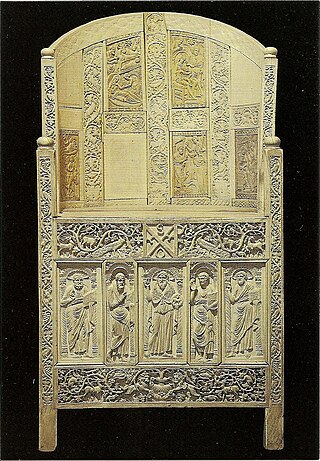

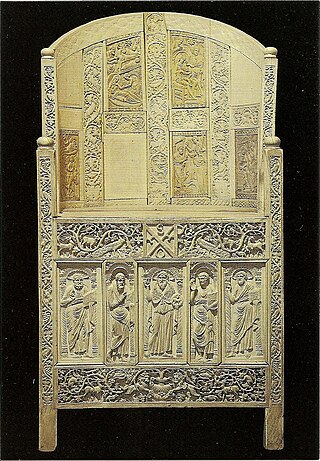

The Throne of Maximian is a cathedra that was made for Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna and is now on display at the Archiepiscopal Museum, Ravenna. It is generally agreed that the throne was carved in the Greek East of the Byzantine Empire and shipped to Ravenna, but there has long been scholarly debate over whether it was made in Constantinople or Alexandria.

The Velletri Sarcophagus is a Roman sarcophagus from 140–150 CE, displaying Greek and possible Asiatic influence. It features Hercules and other pagan deities framed by columned registers of classic spiral-fluted Doric and Ionic columnar styles, creating a theatrical border around the figures. It was created shortly after the Roman conversion to burial practice when Romans went from using cremation to burying their dead, due to new ideas of an afterlife.

The Magdeburg Ivories are a set of 16 surviving ivory panels illustrating episodes of Christ's life. They were commissioned by Emperor Otto I, probably to mark the dedication of Magdeburg Cathedral, and the raising of the Magdeburg see to an archbishopric in 968. The panels were initially part of an unknown object in the cathedral that has been variously conjectured to be an antependium or altar front, a throne, door, pulpit, or an ambon; traditionally this conjectural object, and therefore the ivories as a group, has been called the Magdeburg Antependium. This object is believed to have been dismantled or destroyed in the 1000s, perhaps after a fire in 1049.

The Sarcophagus of Adelphia is an early Christian, circa 340 AD sarcophagus now in the Museo Archeologico Regionale Paolo Orsi in Syracuse, region of Sicily, Italy. The sarcophagus was found in the Rotunda of Adelphia inside the Catacombs of San Giovanni, in Siracusa. The iconography displayed has similarities to the layout of the Dogmatic and Junius Bassus sarcophagi, although the quality of to depictions is simplified.