Quintus Horatius Flaccus, commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his Odes as the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words."

Ludovico Ariosto was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic Orlando Furioso (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato, describes the adventures of Charlemagne, Orlando, and the Franks as they battle against the Saracens with diversions into many sideplots. The poem is transformed into a satire of the chivalric tradition. Ariosto composed the poem in the ottava rima rhyme scheme and introduced narrative commentary throughout the work.

Publius Papinius Statius was a Latin poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the Thebaid; a collection of occasional poetry, the Silvae; and an unfinished epic, the Achilleid. He is also known for his appearance as a guide in the Purgatory section of Dante's epic poem, the Divine Comedy.

Marcus Valerius Martialis was a Roman poet born in Hispania best known for his twelve books of Epigrams, published in Rome between AD 86 and 103, during the reigns of the emperors Domitian, Nerva and Trajan. In these poems he satirises city life and the scandalous activities of his acquaintances, and romanticises his provincial upbringing. He wrote a total of 1,561 epigrams, of which 1,235 are in elegiac couplets.

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on the 17th of December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities until the 19th of December. By the 1st century B.C., the celebration had been extended until the 23rd of December, for a total of seven days of festivities. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

The toga, a distinctive garment of Ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between 12 and 20 feet in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tradition, it is said to have been the favored dress of Romulus, Rome's founder; it was also thought to have originally been worn by both sexes, and by the citizen-military. As Roman women gradually adopted the stola, the toga was recognized as formal wear for male Roman citizens. Women found guilty of adultery and women engaged in prostitution might have provided the main exceptions to this rule.

Aulus Persius Flaccus was a Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satire, he shows a Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he considered to be the stylistic abuses of his poetic contemporaries. His works, which became very popular in the Middle Ages, were published after his death by his friend and mentor, the Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Cornutus.

The mos maiorum is the unwritten code from which the ancient Romans derived their social norms. It is the core concept of Roman traditionalism, distinguished from but in dynamic complement to written law. The mos maiorum was collectively the time-honoured principles, behavioural models, and social practices that affected private, political, and military life in ancient Rome.

Egeria was a nymph attributed a legendary role in the early history of Rome as a divine consort and counselor of Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to whom she imparted laws and rituals pertaining to ancient Roman religion. Her name is used as an eponym for a female advisor or counselor.

Satire VI is the most famous of the sixteen Satires by the Roman author Juvenal written in the late 1st or early 2nd century. In English translation, this satire is often titled something in the vein of Against Women due to the most obvious reading of its content. It enjoyed significant social currency from late antiquity to the early modern period, being read as a proof-text for a wide array of misogynistic beliefs. Its current significance rests in its role as a crucial body of evidence on Roman conceptions of gender and sexuality.

Sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Rome are indicated by art, literature, and inscriptions, and to a lesser extent by archaeological remains such as erotic artifacts and architecture. It has sometimes been assumed that "unlimited sexual license" was characteristic of ancient Rome, but sexuality was not excluded as a concern of the mos maiorum, the traditional social norms that affected public, private, and military life. Pudor, "shame, modesty", was a regulating factor in behavior, as were legal strictures on certain sexual transgressions in both the Republican and Imperial periods. The censors—public officials who determined the social rank of individuals—had the power to remove citizens from the senatorial or equestrian order for sexual misconduct, and on occasion did so. The mid-20th-century sexuality theorist Michel Foucault regarded sex throughout the Greco-Roman world as governed by restraint and the art of managing sexual pleasure.

Homosexuality in ancient Rome often differs markedly from the contemporary West. Latin lacks words that would precisely translate "homosexual" and "heterosexual". The primary dichotomy of ancient Roman sexuality was active / dominant / masculine and passive / submissive / feminine. Roman society was patriarchal, and the freeborn male citizen possessed political liberty (libertas) and the right to rule both himself and his household (familia). "Virtue" (virtus) was seen as an active quality through which a man (vir) defined himself. The conquest mentality and "cult of virility" shaped same-sex relations. Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role. Acceptable male partners were slaves and former slaves, prostitutes, and entertainers, whose lifestyle placed them in the nebulous social realm of infamia, so they were excluded from the normal protections afforded to a citizen even if they were technically free. Freeborn male minors were off limits at certain periods in Rome.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late first and early second centuries AD fix his earliest date of composition. One recent scholar argues that his first book was published in 100 or 101. A reference to a political figure dates his fifth and final surviving book to sometime after 127.

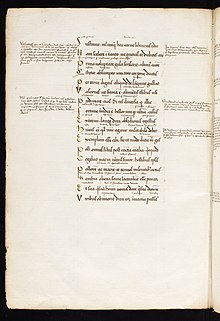

The Satires is a collection of satirical poems written in Latin dactylic hexameters by the Roman poet Horace. Published probably in 35 BC and at the latest, by 33 BC, the first book of Satires represents Horace's first published work. It established him as one of the great poetic talents of the Augustan Age. The second book was published in 30 BC as a sequel.

London is a poem by Samuel Johnson, produced shortly after he moved to London. Written in 1738, it was his first major published work. The poem in 263 lines imitates Juvenal's Third Satire, expressed by the character of Thales as he decides to leave London for Wales. Johnson imitated Juvenal because of his fondness for the Roman poet and he was following a popular 18th-century trend of Augustan poets headed by Alexander Pope that favoured imitations of classical poets, especially for young poets in their first ventures into published verse.

The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson. It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749. It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writing A Dictionary of the English Language and it was the first published work to include Johnson's name on the title page.

Prostitution in ancient Rome was legal and licensed. Men of any social status were free to engage prostitutes of either sex without incurring moral disapproval, as long as they demonstrated self-control and moderation in the frequency and enjoyment of sex. Brothels were part of the culture of ancient Rome, as popular places of entertainment for Roman men.

In ancient Roman religion, Mutunus Tutunus or Mutinus Titinus was a phallic marriage deity, in some respects equated with Priapus. His shrine was located on the Velian Hill, supposedly since the founding of Rome, until the 1st century BC.

Patronage (clientela) was the distinctive relationship in ancient Roman society between the patronus ('patron') and their cliens ('client'). Apart from the patron-client relationship between individuals, there were also client kingdoms and tribes, whose rulers were in a subordinate relationship to the Roman state.

Sulpicia was an ancient Roman poet who was active during the reign of the emperor Domitian. She is mostly known through two poems of Martial; she is also mentioned by Ausonius, Sidonius Apollinaris, and Fulgentius. A seventy-line hexameter poem and two lines of iambic trimeter attributed to her survive; the hexameters are now generally thought to have been a fourth- or fifth-century imitation of Sulpicia. Judging by the ancient references to her and the single surviving couplet of her poetry, Sulpicia wrote love poetry discussing her desire for her husband, and was known for her frank sexuality.