| Sedge wren | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Prairie State Park, Missouri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Troglodytidae |

| Genus: | Cistothorus |

| Species: | C. stellaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Cistothorus stellaris (Naumann, J.F., 1823) | |

| |

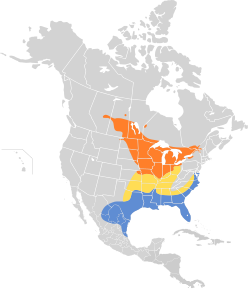

The sedge wren (Cistothorus stellaris) is a small and secretive passerine bird in the family Troglodytidae. It is widely distributed in North America. It is often found in wet grasslands and meadows where it nests in the tall grasses and sedges and feeds on insects. The sedge wren was formerly considered as conspecific with the non-migratory grass wren of central and South America.