The Acts of Union refer to two Acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of England in 1706, the other by the Parliament of Scotland in 1707. They put into effect the Treaty of Union agreed on 22 July 1706, which merged the previously separate Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland into a single Kingdom of Great Britain, with Queen Anne as its sovereign. The Acts took effect on 1 May 1707, creating the Parliament of Great Britain, based in the Palace of Westminster.

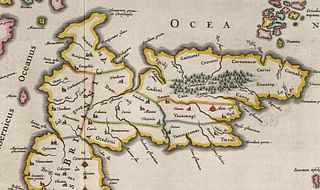

The recorded history of Scotland begins with the arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. North of this was Caledonia, inhabited by the Picti, whose uprisings forced Rome's legions back to Hadrian's Wall. As Rome finally withdrew from Britain, a Gaelic tribe from Ireland called the Scoti began colonising Western Scotland and Wales. Before Roman times, prehistoric Scotland entered the Neolithic Era about 4000 BC, the Bronze Age about 2000 BC, and the Iron Age around 700 BC.

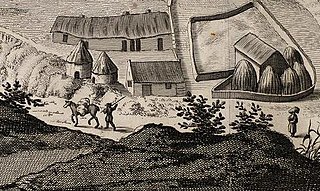

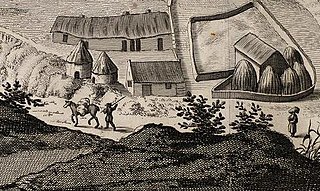

The Agricultural Revolution in Scotland was a series of changes in agricultural practice that began in the 17th century and continued in the 19th century. They began with the improvement of Scottish Lowlands farmland and the beginning of a transformation of Scottish agriculture from one of the least modernised systems to what was to become the most modern and productive system in Europe. The traditional system of agriculture in Scotland generally used the runrig system of management, which had possibly originated in the Late Middle Ages. The basic pre-improvement farming unit was the baile and the fermetoun. In each, a small number of families worked open-field arable and shared grazing. Whilst run rig varied in its detail from place to place, the common defining detail was the sharing out by lot on a regular basis of individual parts ("rigs") of the arable land so that families had intermixed plots in different parts of the field.

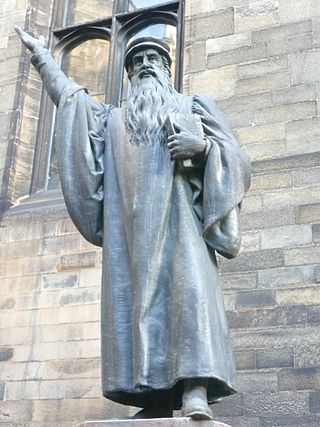

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Agriculture in Scotland includes all land use for arable, horticultural or pastoral activity in Scotland, or around its coasts. The first permanent settlements and farming date from the Neolithic period, from around 6,000 years ago. From the beginning of the Bronze Age, about 2000 BCE, arable land spread at the expense of forest. From the Iron Age, beginning in the seventh century BCE, there was use of cultivation ridges and terraces. During the period of Roman occupation there was a reduction in agriculture and the early Middle Ages were a period of climate deterioration resulting in more unproductive land. Most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet, supplemented by hunter-gathering. More oats and barley were grown, and cattle were the most important domesticated animal. From c. 1150 to 1300, the Medieval Warm Period allowed cultivation at greater heights and made land more productive. The system of infield and outfield agriculture may have been introduced with feudalism from the twelfth century. The rural economy boomed in the thirteenth century, but by the 1360s there was a severe falling off in incomes to be followed by a slow recovery in the fifteenth century.

The economic history of Scotland charts economic development in the history of Scotland from earliest times, through seven centuries as an independent state and following Union with England, three centuries as a country of the United Kingdom. Before 1700 Scotland was a poor rural area, with few natural resources or advantages, remotely located on the periphery of the European world. Outward migration to England, and to North America, was heavy from 1700 well into the 20th century. After 1800 the economy took off, and industrialized rapidly, with textile, coal, iron, railroads, and most famously shipbuilding and banking. Glasgow was the centre of the Scottish economy. After the end of the First World War in 1918, Scotland went into a steady economic decline, shedding thousands of high-paying engineering jobs, and having very high rates of unemployment especially in the 1930s. Wartime demand in the Second World War temporarily reversed the decline, but conditions were difficult in the 1950s and 1960s. The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s brought new wealth, and a new cycle of boom and bust, even as the old industrial base had decayed.

Scotland in the early modern period refers, for the purposes of this article, to Scotland between the death of James IV in 1513 and the end of the Jacobite risings in the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern period in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the start of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution.

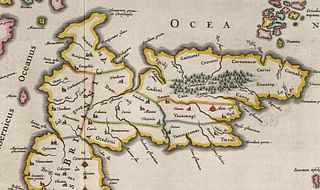

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England. During the Middle Ages, Scotland engaged in intermittent conflict with England, most prominently the Wars of Scottish Independence, which saw the Scots assert their independence from the English. Following the annexation of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles from Norway in 1266 and 1472 respectively, and the capture of Berwick by England in 1482, the territory of the Kingdom of Scotland corresponded to that of modern-day Scotland, bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest.

The Great Famine of 1695–1697, or simply the Great Famine, was a catastrophic famine that affected the present Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Norway and Sweden, all of which belonged to the Swedish Empire with the exception of Norway. The areas worst affected were the Swedish province of Finland and Norrland in Sweden proper.

Scottish society in the early modern era encompasses the social structure and relations that existed in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

The economy of Scotland in the early modern era encompasses all economic activity in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth. The period roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

Government in early modern Scotland included all forms of administration, from the crown, through national institutions, to systems of local government and the law, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Monarchs of this period were the Stuarts: James IV, James V, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI, Charles I, Charles II, James VII, William III and Mary II, Anne, and the Hanoverians: George I and George II.

Women in early modern Scotland, between the Renaissance of the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of industrialisation in the mid-eighteenth century, were part of a patriarchal society, though the enforcement of this social order was not absolute in all aspects. Women retained their family surnames at marriage and did not join their husband's kin groups. In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part. Women were a major part of the workforce, with many unmarried women acting as farm servants and married women playing a part in all the major agricultural tasks, particularly during harvest. Widows could be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading, but many at the bottom of society lived a marginal existence.

Education in early modern Scotland includes all forms of education within the modern borders of Scotland, between the end of the Middle Ages in the late fifteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century. By the sixteenth century such formal educational institutions as grammar schools, petty schools and sewing schools for girls were established in Scotland, while children of the nobility often studied under private tutors. Scotland had three universities, but the curriculum was limited and Scottish scholars had to go abroad to gain second degrees. These contacts were one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life. Humanist concern with education and Latin culminated in the Education Act 1496.

The demographic history of Scotland includes all aspects of population history in what is now Scotland. The earliest surviving archaeological evidence of human settlement is of Mesolithic hunter-gatherer encampments. These suggest a highly mobile boat-using people, probably with a very low density of population. Neolithic farming brought permanent settlements dating from 3500 BC, and greater concentrations of population. Evidence of hillforts and other buildings suggest a growing settled population. Changes in the scale of woodland indicates that the Roman invasions from the first century AD had a negative impact on the native population.

The geography of Scotland in the early modern era covers all aspects of the land in Scotland, including physical and human, between the sixteenth century and the beginnings of the Agricultural Revolution and industrialisation in the eighteenth century. The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands were subdivided by the Great Glen and the Lowlands into the fertile Central Lowlands and the Southern Uplands. The Uplands and Highlands had a relatively short growing season, exacerbated by the Little Ice Age, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century.

The history of agriculture in Scotland includes all forms of farm production in the modern boundaries of Scotland, from the prehistoric era to the present day.

Agriculture in Scotland in the early modern era includes all forms of farm production in the modern boundaries of Scotland, between the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-eighteenth century. This era saw the impact of the Little Ice Age, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century. Almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century saw local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic. In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, but became rarer as the century progressed. The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw a slump, followed by four years of failed harvests, in what is known as the "seven ill years", but these shortages would be the last of their kind.

Scottish trade in the early modern era includes all forms of economic exchange within Scotland and between the country and locations outwith its boundaries, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth. The period roughly corresponds to the early modern era, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.

Sir Thomas Martin Devine is a Scottish academic and author who specializes in the history of Scotland. He was knighted and made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for his contributions to Scottish historiography, and is known for his overviews of modern Scottish history. He is an advocate of the total history approach to the history of Scotland. He is professor emeritus at the University of Edinburgh, and was formerly a professor at the University of Strathclyde and the University of Aberdeen.