Related Research Articles

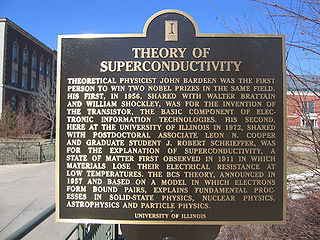

In physics, the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory is the first microscopic theory of superconductivity since Heike Kamerlingh Onnes's 1911 discovery. The theory describes superconductivity as a microscopic effect caused by a condensation of Cooper pairs. The theory is also used in nuclear physics to describe the pairing interaction between nucleons in an atomic nucleus.

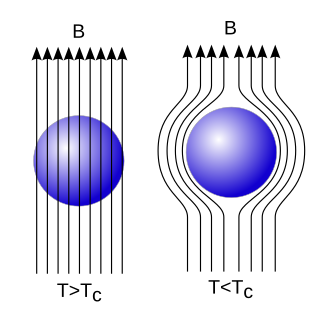

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in superconductors: materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic fields are expelled from the material. Unlike an ordinary metallic conductor, whose resistance decreases gradually as its temperature is lowered, even down to near absolute zero, a superconductor has a characteristic critical temperature below which the resistance drops abruptly to zero. An electric current through a loop of superconducting wire can persist indefinitely with no power source.

A SQUID is a very sensitive magnetometer used to measure extremely weak magnetic fields, based on superconducting loops containing Josephson junctions.

In condensed-matter physics, the Meissner effect is the expulsion of a magnetic field from a superconductor during its transition to the superconducting state when it is cooled below the critical temperature. This expulsion will repel a nearby magnet.

High-temperature superconductivity is superconductivity in materials with a critical temperature above 77 K, the boiling point of liquid nitrogen. They are only "high-temperature" relative to previously known superconductors, which function at colder temperatures, close to absolute zero. The "high temperatures" are still far below ambient, and therefore require cooling. The first breakthrough of high-temperature superconductor was discovered in 1986 by IBM researchers Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller. Although the critical temperature is around 35.1 K, this new type of superconductor was readily modified by Ching-Wu Chu to make the first high-temperature superconductor with critical temperature 93 K. Bednorz and Müller were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1987 "for their important break-through in the discovery of superconductivity in ceramic materials". Most high-Tc materials are type-II superconductors.

Magnesium diboride is the inorganic compound of magnesium and boron with the formula MgB2. It is a dark gray, water-insoluble solid. The compound has attracted attention because it becomes superconducting at 39 K (−234 °C). In terms of its composition, MgB2 differs strikingly from most low-temperature superconductors, which feature mainly transition metals. Its superconducting mechanism is primarily described by BCS theory.

A superconducting magnet is an electromagnet made from coils of superconducting wire. They must be cooled to cryogenic temperatures during operation. In its superconducting state the wire has no electrical resistance and therefore can conduct much larger electric currents than ordinary wire, creating intense magnetic fields. Superconducting magnets can produce stronger magnetic fields than all but the strongest non-superconducting electromagnets, and large superconducting magnets can be cheaper to operate because no energy is dissipated as heat in the windings. They are used in MRI instruments in hospitals, and in scientific equipment such as NMR spectrometers, mass spectrometers, fusion reactors and particle accelerators. They are also used for levitation, guidance and propulsion in a magnetic levitation (maglev) railway system being constructed in Japan.

Superconductivity is the phenomenon of certain materials exhibiting zero electrical resistance and the expulsion of magnetic fields below a characteristic temperature. The history of superconductivity began with Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes's discovery of superconductivity in mercury in 1911. Since then, many other superconducting materials have been discovered and the theory of superconductivity has been developed. These subjects remain active areas of study in the field of condensed matter physics.

Superdiamagnetism is a phenomenon occurring in certain materials at low temperatures, characterised by the complete absence of magnetic permeability and the exclusion of the interior magnetic field.

Bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide (BSCCO, pronounced bisko), is a type of cuprate superconductor having the generalized chemical formula Bi2Sr2Can−1CunO2n+4+x, with n = 2 being the most commonly studied compound (though n = 1 and n = 3 have also received significant attention). Discovered as a general class in 1988, BSCCO was the first high-temperature superconductor which did not contain a rare-earth element.

Cryogenic particle detectors operate at very low temperature, typically only a few degrees above absolute zero. These sensors interact with an energetic elementary particle and deliver a signal that can be related to the type of particle and the nature of the interaction. While many types of particle detectors might be operated with improved performance at cryogenic temperatures, this term generally refers to types that take advantage of special effects or properties occurring only at low temperature.

In superconductivity, a type-II superconductor is a superconductor that exhibits an intermediate phase of mixed ordinary and superconducting properties at intermediate temperature and fields above the superconducting phases. It also features the formation of magnetic field vortices with an applied external magnetic field. This occurs above a certain critical field strength Hc1. The vortex density increases with increasing field strength. At a higher critical field Hc2, superconductivity is destroyed. Type-II superconductors do not exhibit a complete Meissner effect.

Lev Vasilyevich Shubnikov was a Soviet experimental physicist who worked in the Netherlands and USSR. He has been referred as the as 'the founding father of Soviet low-temperature physics'. He is known for the discovery of the Shubnikov–de Haas effect and type-II superconductivity. He also one of the first to discover antiferromagnetism.

Anatoly Ivanovich Larkin was a Russian theoretical physicist, universally recognised as a leader in theory of condensed matter, and who was also a celebrated teacher of several generations of theorists.

Proximity effect or Holm–Meissner effect is a term used in the field of superconductivity to describe phenomena that occur when a superconductor (S) is placed in contact with a "normal" (N) non-superconductor. Typically the critical temperature of the superconductor is suppressed and signs of weak superconductivity are observed in the normal material over mesoscopic distances. The proximity effect is known since the pioneering work by R. Holm and W. Meissner. They have observed zero resistance in SNS pressed contacts, in which two superconducting metals are separated by a thin film of a non-superconducting metal. The discovery of the supercurrent in SNS contacts is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Brian Josephson's 1962 work, yet the effect was known long before his publication and was understood as the proximity effect.

Superconductors can be classified in accordance with several criteria that depend on physical properties, current understanding, and the expense of cooling them or their material.

Superconducting wires are electrical wires made of superconductive material. When cooled below their transition temperatures, they have zero electrical resistance. Most commonly, conventional superconductors such as niobium–titanium are used, but high-temperature superconductors such as YBCO are entering the market.

The superconducting tunnel junction (STJ) – also known as a superconductor–insulator–superconductor tunnel junction (SIS) – is an electronic device consisting of two superconductors separated by a very thin layer of insulating material. Current passes through the junction via the process of quantum tunneling. The STJ is a type of Josephson junction, though not all the properties of the STJ are described by the Josephson effect.

Macroscopic quantum phenomena are processes showing quantum behavior at the macroscopic scale, rather than at the atomic scale where quantum effects are prevalent. The best-known examples of macroscopic quantum phenomena are superfluidity and superconductivity; other examples include the quantum Hall effect, Josephson effect and topological order. Since 2000 there has been extensive experimental work on quantum gases, particularly Bose–Einstein condensates.

Several hundred metals, compounds, alloys and ceramics possess the property of superconductivity at low temperatures. The SU(2) color quark matter adjoins the list of superconducting systems. Although it is a mathematical abstraction, its properties are believed to be closely related to the SU(3) color quark matter, which exists in nature when ordinary matter is compressed at supranuclear densities above ~ 0.5 1039 nucleon/cm3.

References

- ↑ Scfalig, Eugene (29 May 1959). Patent US3119076 . Retrieved 24 January 2013.[ dead link ]

- ↑ Solid State Physics. N. W. Ashcroft, N. D. Mermin, 1976, ISBN 0030839939

- ↑ Silsbee, F. B. (1918). "Note on electrical conduction in metals at low temperatures". Bulletin of the Bureau of Standards. 14 (2): 301. doi: 10.6028/bulletin.335 . ISSN 0096-8579.