Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliating with another. This might be from one to another denomination within the same religion, for example, from Protestant Christianity to Roman Catholicism or from Shi'a Islam to Sunni Islam. In some cases, religious conversion "marks a transformation of religious identity and is symbolized by special rituals".

Subud is an international, interfaith spiritual movement that began in Indonesia in the 1920s, founded by Muhammad Subuh Sumohadiwidjojo (1901–1987). The basis of Subud is a spiritual exercise called the latihan kejiwaan, which Muhammad Subuh said represents guidance from "the Power of God" or "the Great Life Force."

Universalism is the philosophical concept and a theological concept within Christianity that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

Religion in Japan is manifested primarily in Shinto and in Buddhism, the two main faiths, which Japanese people often practice simultaneously. According to estimates, as many as 70% of the populace follow Shinto rituals to some degree, worshiping ancestors and spirits at domestic altars and public shrines. An almost equally high number is reported as Buddhist. Syncretic combinations of both, known generally as shinbutsu-shūgō, are common; they represented Japan's dominant religion before the rise of State Shinto in the 19th century.

Comparative religion is the branch of the study of religions with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices, themes and impacts of the world's religions. In general the comparative study of religion yields a deeper understanding of the fundamental philosophical concerns of religion such as ethics, metaphysics and the nature and forms of salvation. It also considers and compares the origins and similarities shared between the various religions of the world. Studying such material facilitates a broadened and more sophisticated understanding of human beliefs and practices regarding the sacred, numinous, spiritual and divine.

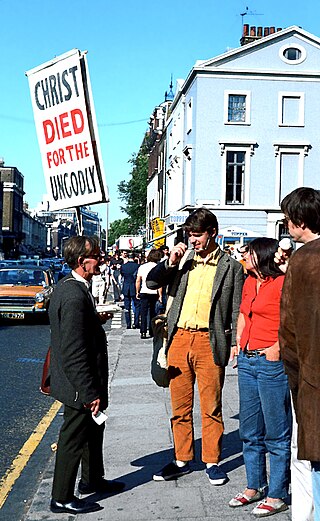

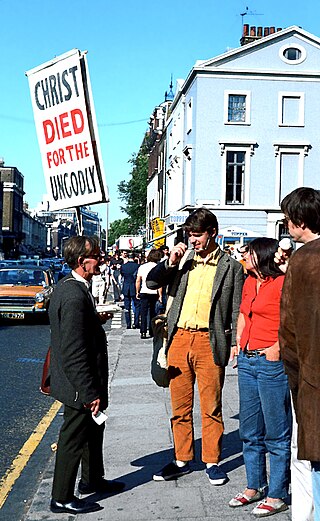

Proselytism is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Carrying out attempts to instill beliefs can be called proselytization.

In the field of comparative religion, many scholars, academics, and religious figures have looked at the relationships between Hinduism and other religions.

Sahaja Yoga is a religion founded in 1970 by Nirmala Srivastava (1923–2011). Nirmala Srivastava is known as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi or simply as "Mother" by her followers, who are called Sahaja yogis.

Religion in Singapore is characterised by a wide variety of religious beliefs and practices due to its diverse ethnic mix of people originating from various parts of the world. A secular state, Singapore is commonly termed as a "melting pot" or "cultural mosaic " of various religious practices originating from different religions and religious denominations around the world. Most major religious denominations are present in the country, with the Singapore-based Inter-Religious Organisation recognising 10 major religions. A 2014 analysis by the Pew Research Center found Singapore to be the world's most religiously diverse nation.

Latihan is a form of spiritual practice. It is the principal practice of the Subud organization.

A spiritual practice or spiritual discipline is the regular or full-time performance of actions and activities undertaken for the purpose of inducing spiritual experiences and cultivating spiritual development. A common metaphor used in the spiritual traditions of the world's great religions is that of walking a path. Therefore, a spiritual practice moves a person along a path towards a goal. The goal is variously referred to as salvation, liberation or union. A person who walks such a path is sometimes referred to as a wayfarer or a pilgrim.

Kejawèn or Javanism, also called Kebatinan, Agama Jawa, and Kepercayaan, is a Javanese cultural tradition, consisting of an amalgam of Animistic, Buddhist, Islamic and Hindu aspects. It is rooted in Javanese history and religiosity, syncretizing aspects of different religions and traditions.

The majority of Vietnamese do not follow any organized religion, instead participating in one or more practices of folk religions, such as venerating ancestors, or praying to deities, especially during Tết and other festivals. Folk religions were founded on endemic cultural beliefs that were historically affected by Confucianism and Taoism from ancient China, as well as by various strands of Buddhism. These three teachings or tam giáo were later joined by Christianity which has become a significant presence. Vietnam is also home of two indigenous religions: syncretic Caodaism and quasi-Buddhist Hoahaoism.

This is a glossary of spirituality-related terms. Spirituality is closely linked to religion.

Secular spirituality is the adherence to a spiritual philosophy without adherence to a religion. Secular spirituality emphasizes the inner peace of the individual, rather than a relationship with the divine. Secular spirituality is made up of the search for meaning outside of a religious institution; it considers one's relationship with the self, others, nature, and whatever else one considers to be the ultimate. Often, the goal of secular spirituality is living happily and/or helping others.

Hinduism in Mongolia is a minority religion; it has few followers and only began to appear in Mongolia in the late twentieth century. According to the 2010 and 2011 Mongolian census, the majority of people that identify as religious follow Buddhism (86%), Shamanism (4.7), Islam (4.9%) or Christianity (3.5). Only 0.5% of the population follow other religions.

Theravada Buddhism is the largest and dominant religion in Laos. Theravada Buddhism is central to Lao cultural identity. The national symbol of Laos is the That Luang stupa, a stupa with a pyramidal base capped by the representation of a closed lotus blossom which was built to protect relics of the Buddha. It is practiced by 66% of the population. Almost all ethnic or "lowland" Lao people are followers of Theravada Buddhism; however, they constitute more than 50% of the population. The remainder of the population belongs to at least 48 distinct ethnic minority groups. Most of these ethnic groups are practitioners of Tai folk religions, with beliefs that vary greatly among groups.

The Constitution of Mongolia provides for freedom of religion; however, the law somewhat limits proselytism.

Religious syncretism is the blending of religious belief systems into a new system, or the incorporation of other beliefs into an existing religious tradition.