Artistic career

Little is known of Harunobu's early life; his birthplace and birthdate are unknown, but it is believed he grew up in Kyoto. It is said he was 46 at his death in 1770. Unlike most ukiyo-e artists, Harunobu used his real name rather than an artist name. He was from a samurai family, and had an ancestor who was a retainer of Tokugawa Ieyasu in Mikawa Province; this Suzuki accompanied Ieyasu to Edo when the latter had his capital built there. Harunobu's grandfather Shigemitsu and father Shigekazu were stripped of their hatamoto status when they were found to be involved in financing of gambling and other activities; they were exiled from Edo and relocated to Kyoto. At some point, Harunobu became a student of the ukiyo-e master Nishikawa Sukenobu.

Harunobu began his career in the style of the Torii school, creating many works which, while skillful, were not innovative and did not stand out. It was only through his involvement with a group of literati samurai that Harunobu tackled new formats and styles.

In 1764, as a result of his social connections, he was chosen to aid these samurai in their amateur efforts to create e-goyomi [ ja ]. Calendars prints of this sort from prior to that year are not unknown but are quite rare, and it is known that Harunobu was close acquaintances or friends with many of the prominent artists and scholars of the period, as well as with several friends of the shōgun . Harunobu's calendars, which incorporated the calculations of the lunar calendar into their images, would be exchanged at Edo gatherings and parties.

These calendar prints would be the very first nishiki-e (brocade prints). As a result of the wealth and connoisseurship of his samurai patrons, Harunobu exclusively created these prints using the best materials available. Harunobu experimented with better woods for the woodblocks, using cherry wood instead of catalpa, and used not only more expensive colors, but also a thicker application of the colors, in order to achieve a more opaque effect.

The most important of Harunobu's innovations in the creation of nishiki-e was the use of multiple separate wood blocks in the creation of a single image, an expense afforded through the wealth of his clients. Just 20 years previously, the invention of benizuri-e had made it possible to print in three or four colors; Harunobu applied this new technique to ukiyo-e prints using up to ten different colors on a single sheet of paper. The new technique depended on using notches and wedges to hold the paper in place and keep the successive color printings in register. Harunobu was the first ukiyo-e artist to consistently use more than three colors in each print. Nishiki-e, unlike their predecessors, were full-color images. As the technique was first used in a calendar, the year of their origin can be traced precisely to 1765.

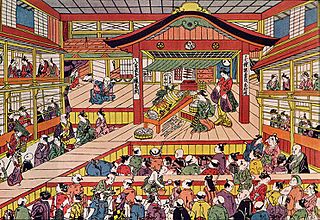

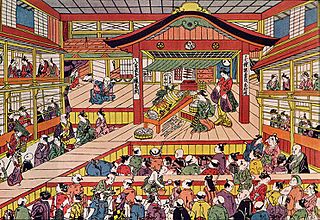

In the late 1760s, Harunobu thus became one of the primary producers of images of bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women), actors of Edo and related subjects for the Edo print connoisseur market; however, he did not produce prints of kabuki actors, reported to have said, "Why should I paint pictures of such trash as Kabuki actors". [2] In a few special cases, notably his famous set of eight prints entitled Zashiki hakkei (Eight Parlor Views), the patron's name appears on the print along with, or in place of, Harunobu's own. The presence of a patron's name or seal, and especially the omission of that of the artist, was another novel development in ukiyo-e of this time.

Between 1765 and 1770, Harunobu created over twenty illustrated books and over one thousand color prints, along with a number of paintings. He came to be regarded as the master of ukiyo-e during these last years of his life, and was widely imitated until, a number of years after his death, his style was eclipsed by that of new artists, including Katsukawa Shunshō and Torii Kiyonaga.

Style

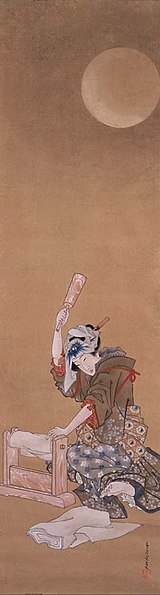

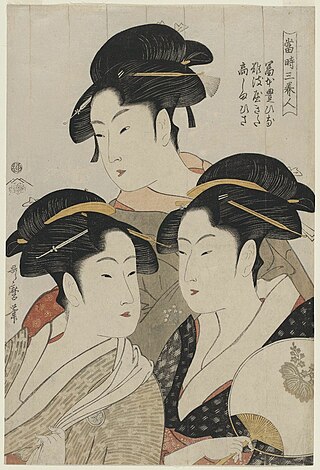

In addition to the revolutionary innovations that came with the introduction of nishiki-e, Harunobu's personal style was unique in a number of other respects. His figures are all very thin and light; some critics say that all his figures look like children. However, it is these same young girls who epitomize Harunobu's personal style. Richard Lane describes this as "Harunobu's special province, one in which he surpassed all other Japanese artists - eternal girlhood in unusual and poetic settings". [3] Though his compositions, like most ukiyo-e prints, may be said to be fairly simple overall, it is the overall composition that concerned Harunobu. Unlike many of his predecessors, he did not seek to have the girls' kimono dominate the viewer's attention.

Harunobu is also acclaimed as being one of the greatest artists of this period in depicting ordinary urban life in Edo. His subjects are not restricted to geisha, courtesans, actors, and sumo wrestlers, but include street vendors, errand boys, and others who help to fill in the gaps in describing the culture of this time. His work is rich in literary allusion, and he often quotes Japanese classical poetry, but the accompanying illustrations often gently poke fun at the subject.

Many of his prints have a solid, single-color background, created by a technique called tsubushi. Though many other artists used the same technique, Harunobu is generally regarded as having used it to the strongest effect. The colored background sets a mood and tone for the entire image.

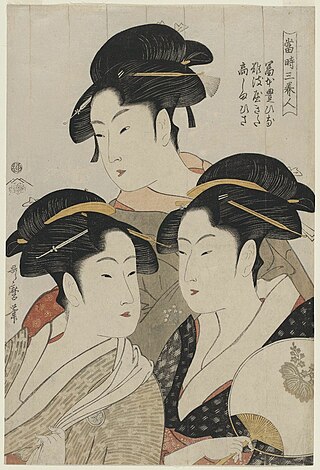

Kitagawa Utamaro was a Japanese artist. He is one of the most highly regarded designers of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings, and is best known for his bijin ōkubi-e "large-headed pictures of beautiful women" of the 1790s. He also produced nature studies, particularly illustrated books of insects.

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e translates as 'picture[s] of the floating world'.

Shunga (春画) is a type of Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e, often in woodblock print format. While rare, there are also extant erotic painted handscrolls which predate ukiyo-e. Translated literally, the Japanese word shunga means picture of spring; "spring" is a common euphemism for sex.

Nishiki-e is a type of Japanese multi-coloured woodblock printing; the technique is used primarily in ukiyo-e. It was invented in the 1760s, and perfected and popularized by the printmaker Suzuki Harunobu, who produced many nishiki-e prints between 1765 and his death five years later.

Bijin-ga is a generic term for pictures of beautiful women in Japanese art, especially in woodblock printing of the ukiyo-e genre.

Kitao Shigemasa was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist from Edo. He was one of the leading printmakers of his day, but his works have been slightly obscure. He is noted for images of beautiful women (bijinga). He was taught by Shigenaga and has been referred to as "a chameleon" who adapted to changing styles. He was less active after the rise of Torii Kiyonaga and produced relatively few works considering the length of his career. He is also noted for his haikai (poetry) and shodō. In his later years he used the studio name Kosuisai.

Torii Kiyonaga was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Torii school. Originally Sekiguchi Shinsuke, the son of an Edo bookseller, from Motozaimokuchō Itchōme in Edo, he took on Torii Kiyonaga as an art name. Although not biologically related to the Torii family, he became head of the group after the death of his adoptive father and teacher Torii Kiyomitsu.

Nishikawa Sukenobu, often called simply "Sukenobu", was a Japanese printmaker from Kyoto. He was unusual for an ukiyo-e artist, as he was based in the imperial capital of Kyoto. He did prints of actors, but gained note for his works concerning women. His Hyakunin joro shinasadame, in two volumes published in 1723, depicted women of all classes, from the empress to prostitutes, and received favorable results.

Isoda Koryūsai was a Japanese ukiyo-e print designer and painter active from 1769 to 1790.

Miyagawa Chōshun was a Japanese painter in the ukiyo-e style. Founder of the Miyagawa school, he and his pupils are among the few ukiyo-e artists to have never created woodblock prints. He was born in Miyagawa, in Owari Province, but lived much of his later life in Edo, where he died.

Woodblock printing in Japan is a technique best known for its use in the ukiyo-e artistic genre of single sheets, but it was also used for printing books in the same period. Invented in China during the Tang dynasty, woodblock printing was widely adopted in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1868). It is similar to woodcut in Western printmaking in some regards, but was widely used for text as well as images. The Japanese mokuhanga technique differs in that it uses water-based inks—as opposed to Western woodcut, which typically uses oil-based inks. The Japanese water-based inks provide a wide range of vivid colors, glazes, and transparency.

Torii Kiyomitsu was a painter and printmaker of the Torii school of Japanese ukiyo-e art; the son of Torii Kiyonobu II or Torii Kiyomasu II, he was the third head of the school, and was originally called Kamejirō before taking the gō Kiyomitsu. Dividing his work between actor prints and bijinga, he primarily used the benizuri-e technique prolific at the time, which involved using one or two colors of ink on the woodblocks rather than hand-coloring; full-color prints would be introduced later in Kiyomitsu's career, in 1765.

Ishikawa Toyonobu was a Japanese ukiyo-e print artist. He is sometimes said to have been the same person as Nishimura Shigenobu, a contemporary ukiyo-e artist and student of Nishimura Shigenaga about whom very little is known.

Richard Douglas Lane (1926–2002) was an American art critic, collector, dealer, historian, and writer. He was dealer of Japanese art, lived in Japan for much of his life, and had a long association with the Honolulu Museum of Art in Hawaii, which now holds his vast art collection.

Utagawa Toyoharu was a Japanese artist in the ukiyo-e genre, known as the founder of the Utagawa school and for his uki-e pictures that incorporated Western-style geometrical perspective to create a sense of depth.

E-hon is the Japanese term for picture books. It may be applied in the general sense, or may refer specifically to a type of woodblock printed illustrated volume published in the Edo period (1603–1867).

The two ukiyo-e woodblock prints making up View of Tempōzan Park in Naniwa are half of a tetraptych by Osaka artist Gochōtei Sadamasu. They depict a scene of crowds visiting Mount Tempō in springtime to admire its natural beauty. The sheets belong to the permanent collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada.

Zashiki Hakkei is a series of eight prints from 1766 by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Suzuki Harunobu. They were the first full-colour nishiki-e prints and are considered representative examples of Harunobu's work. The prints are mitate-e parodies of popular themes of the 11th-century Chinese landscape painting series, Eight Views of Xiaoxiang; Harunobu replaces natural scenery with domestic scenes.

Tachibana Minkō was a Japanese artist of the Edo period. His art name was Gyokujuken. Originally an embroiderer working in metal foils in Osaka, he later became a woodblock printer and moved to Edo. He is particularly famous for his illustrated book Saiga Shokunin Burui which further developed techniques of stencil printing (kappazuri).