The sonata form is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th century.

The Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98 by Johannes Brahms is the last of his symphonies. Brahms began working on the piece in Mürzzuschlag, then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1884, just a year after completing his Symphony No. 3. Brahms conducted the Court Orchestra in Meiningen, Germany, for the work's premiere on 25 October 1885.

The Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93 is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1812. Beethoven fondly referred to it as "my little Symphony in F", distinguishing it from his Sixth Symphony, a longer work also in F.

The Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34, by Johannes Brahms was completed during the summer of 1864 and published in 1865. It was dedicated to Her Royal Highness Princess Anna of Hesse. As with most piano quintets composed after Robert Schumann's Piano Quintet (1842), it is written for piano and string quartet.

The Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36, is a symphony in four movements written by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1801 and 1802. The work is dedicated to Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky.

The Symphony No. 104 in D major is Joseph Haydn's final symphony. It is the last of the twelve London symphonies, and is known as the London Symphony. In Germany it is commonly known as the Salomon Symphony after Johann Peter Salomon, who arranged Haydn's two tours of London, even though it is one of three of the last twelve symphonies written for Viotti's Opera Concerts, rather than for Salomon.

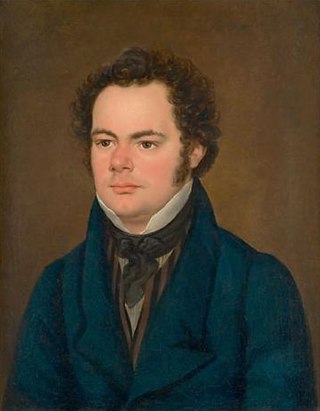

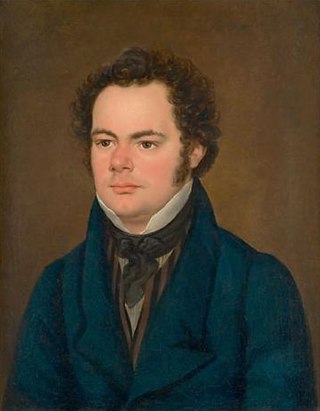

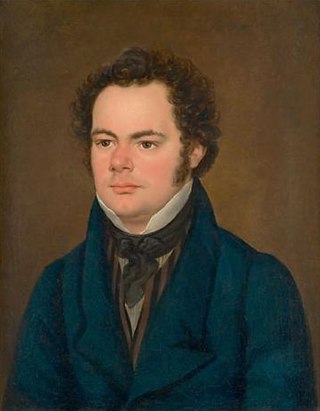

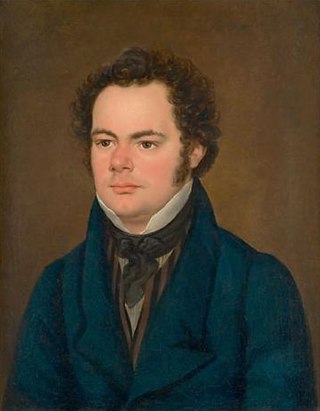

The Symphony No. 9 in C major, D 944, known as The Great, is the final symphony completed by Franz Schubert. It was first published by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1849 as "Symphonie / C Dur / für großes Orchester" and listed as Symphony No. 8 in the New Schubert Edition. Originally called The Great C major to distinguish it from his Symphony No. 6, the Little C major, the subtitle is now usually taken as a reference to the symphony's majesty. Unusually long for a symphony of its time, a typical performance of The Great lasts around one hour when all repeats indicated in the score are taken. The symphony was not professionally performed until a decade after Schubert's death in 1828.

An unfinished symphony is a fragment of a symphony that is left incomplete. The reason as of why and the state of the sketches themselves can vary considerably. The death of the composer is the most common cause for a symphony to be left unfinished, but it can also be abandoned due to lack of progress, frustration or changes in style, among other issues. Even when a symphony is complete, parts of it may be lost later on, thus technically making the work "unfinished" even if the composer actually finished it. Sketches can range from a few notes and motives, to complete works in short score or unorchestrated manuscripts. When a symphony is left unfinished, it may remain in that state or be completed through various means.

The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was composed between May and August 1888 and was first performed in Saint Petersburg at the Mariinsky Theatre on November 17 of that year with Tchaikovsky conducting. It is dedicated to Theodor Avé-Lallemant.

The Symphony No. 6 in A major, WAB 106, by Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) is a work in four movements composed between 24 September 1879, and 3 September 1881 and dedicated to his landlord, Anton van Ölzelt-Newin. Only two movements from it were performed in public in the composer's lifetime. Though it possesses many characteristic features of a Bruckner symphony, it differs the most from the rest of his symphonic repertory. Redlich went so far as to cite the lack of hallmarks of Bruckner's symphonic compositional style in the Sixth Symphony for the somewhat bewildered reaction of supporters and critics alike.

The Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, is a symphony written by Johannes Brahms. Brahms spent at least fourteen years completing this work, whose sketches date from 1854. Brahms himself declared that the symphony, from sketches to finishing touches, took 21 years, from 1855 to 1876. The premiere of this symphony, conducted by the composer's friend Felix Otto Dessoff, occurred on 4 November 1876, in Karlsruhe, then in the Grand Duchy of Baden. A typical performance lasts between 45 and 50 minutes.

The String Quartet No. 13 in A minor, D 804, Op. 29, was written by Franz Schubert between February and March 1824. It dates roughly to the same time as his monumental Death and the Maiden Quartet, emerging around three years after his previous attempt to write for the string quartet genre, the Quartettsatz, D 703, that he never finished.

Schubert's Symphony No. 10 in D major, D 936A, is an unfinished work that survives in a piano sketch. Written during the last weeks of the composer's short life, it was only properly identified in the 1970s. It has been orchestrated by Brian Newbould in a completion that has subsequently been performed, published and recorded.

Franz Schubert's Piano Sonata in A minor, D 784, is one of Schubert's major compositions for the piano. Schubert composed the work in February 1823, perhaps as a response to his illness the year before. It was however not published until 1839, eleven years after his death. It was given the opus number 143 and a dedication to Felix Mendelssohn by its publishers. The D 784 sonata, Schubert's last to be in three movements, is seen by many to herald a new era in Schubert's output for the piano, and to be a profound and sometimes almost obsessively tragic work.

Franz Schubert's last three piano sonatas, D 958, 959 and 960, are his last major compositions for solo piano. They were written during the last months of his life, between the spring and autumn of 1828, but were not published until about ten years after his death, in 1838–39. Like the rest of Schubert's piano sonatas, they were mostly neglected in the 19th century. By the late 20th century, however, public and critical opinion had changed, and these sonatas are now considered among the most important of the composer's mature masterpieces. They are part of the core piano repertoire, appearing regularly on concert programs and recordings.

The Fantasia in F minor by Franz Schubert, D.940, for piano four hands, is one of Schubert's most important works for more than one pianist and one of his most important piano works altogether. He composed it in 1828, the last year of his life. A dedication to his former pupil Caroline Esterházy can only be found in the posthumous first edition, not in Schubert's autograph.

Brian Newbould is an English composer, conductor and author who has conjecturally completed Franz Schubert's Symphonies D 708A in D major, No. 7 in E major, No. 8 in B minor ("Unfinished"), No. 10 ("Last") in D major, Piano Sonata in C major, D 840, Quartettsatz, D. 703 and String Trio, D. 471. He was educated at Gravesend Grammar School, and earned a BMus degree with top honors from the University of Bristol.

Schubert's Symphony in D major, D 708A, is an unfinished work that survives in an incomplete eleven-page sketch written for piano solo. It is one of Schubert's six unfinished symphonies. It was begun in 1820 or 1821, with initial sketches made for the opening sections of the first, second, and fourth movements, and an almost complete sketch for the third movement. He abandoned this symphony after this initial phase of work and never returned to it, although Schubert would live for another seven years. British conductor and composer Brian Newbould, an authority on Schubert's music, has speculated that the symphony was left incomplete due to problems Schubert faced in orchestrating the sketch.

Schubert's Symphony in D major, D 615, is an unfinished work that survives in an incomplete four-page, 259-bar sketch written for piano solo. It is one of Schubert's six unfinished symphonies. It was begun in May 1818, with initial sketches made for the opening sections of the first movement and finale. He abandoned this symphony after this initial phase of work and never returned to it, probably due to dissatisfaction with it, although Schubert would live for another ten years. Although conductor and composer Brian Newbould has made a performing version of the fragments, a full completion has not yet been attempted.

Franz Schubert began thirteen symphonies, of which up to ten are generally numbered, but only completed seven; nonetheless, one of his incomplete symphonies, the Unfinished Symphony, is among his most popular works. Four of the six incomplete symphonies have been completed by other hands.