Related Research Articles

The citric acid cycle (CAC)—also known as the Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle —is a series of chemical reactions to release stored energy through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The Krebs cycle is used by organisms that respire to generate energy, either by anaerobic respiration or aerobic respiration. In addition, the cycle provides precursors of certain amino acids, as well as the reducing agent NADH, that are used in numerous other reactions. Its central importance to many biochemical pathways suggests that it was one of the earliest components of metabolism and may have originated abiogenically. Even though it is branded as a 'cycle', it is not necessary for metabolites to follow only one specific route; at least three alternative segments of the citric acid cycle have been recognized.

Oxidative phosphorylation or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In eukaryotes, this takes place inside mitochondria. Almost all aerobic organisms carry out oxidative phosphorylation. This pathway is so pervasive because it releases more energy than alternative fermentation processes such as anaerobic glycolysis.

A dehydrogenase is an enzyme belonging to the group of oxidoreductases that oxidizes a substrate by reducing an electron acceptor, usually NAD+/NADP+ or a flavin coenzyme such as FAD or FMN. Like all catalysts, they catalyze reverse as well as forward reactions, and in some cases this has physiological significance: for example, alcohol dehydrogenase catalyzes the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde in animals, but in yeast it catalyzes the production of ethanol from acetaldehyde.

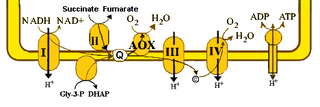

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples this electron transfer with the transfer of protons (H+ ions) across a membrane. The electrons that transferred from NADH and FADH2 to the ETC involves 4 multi-subunit large enzymes complexes and 2 mobile electron carriers. Many of the enzymes in the electron transport chain are membrane-bound.

Smegma is a combination of shed skin cells, skin oils, and moisture. It occurs in both male and female mammalian genitalia. In females, it collects around the clitoris and in the folds of the labia minora; in males, smegma collects under the foreskin.

The Pseudomonadaceae are a family of bacteria which includes the genera Azomonas, Azorhizophilus, Azotobacter, Mesophilobacter, Pseudomonas, and Rugamonas. The family Azotobacteraceae was recently reclassified into this family.

Haemophilus is a genus of Gram-negative, pleomorphic, coccobacilli bacteria belonging to the family Pasteurellaceae. While Haemophilus bacteria are typically small coccobacilli, they are categorized as pleomorphic bacteria because of the wide range of shapes they occasionally assume. These organisms inhabit the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract, mouth, vagina, and intestinal tract. The genus includes commensal organisms along with some significant pathogenic species such as H. influenzae—a cause of sepsis and bacterial meningitis in young children—and H. ducreyi, the causative agent of chancroid. All members are either aerobic or facultatively anaerobic. This genus has been found to be part of the salivary microbiome.

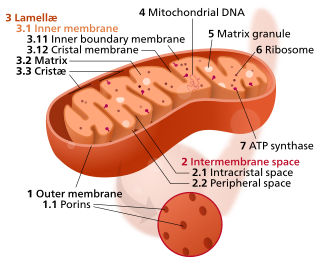

The inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is the mitochondrial membrane which separates the mitochondrial matrix from the intermembrane space.

The alternative oxidase (AOX) is an enzyme that forms part of the electron transport chain in mitochondria of different organisms. Proteins homologous to the mitochondrial oxidase and the related plastid terminal oxidase have also been identified in bacterial genomes.

Contagious equine metritis (CEM) is a type of metritis in horses that is caused by a sexually transmitted infection. It is thus an equine venereal disease of the genital tract of horses, brought on by the Taylorella equigenitalis bacteria and spread through sexual contact. The disease was first reported in 1977, and has since been reported worldwide.

Glutaminolysis (glutamine + -lysis) is a series of biochemical reactions by which the amino acid glutamine is lysed to glutamate, aspartate, CO2, pyruvate, lactate, alanine and citrate.

Streptococcus zooepidemicus is a Lancefield group C streptococcus that was first isolated in 1934 by P. R. Edwards, and named Animal pyogens A. It is a mucosal commensal and opportunistic pathogen that infects several animals and humans, but most commonly isolated from the uterus of mares. It is a subspecies of Streptococcus equi, a contagious upper respiratory tract infection of horses, and shares greater than 98% DNA homology, as well as many of the same virulence factors.

The Arc system is a two-component system found in some bacteria that regulates gene expression in faculatative anaerobes such as Escheria coli. Two-component system means that it has a sensor molecule and a response regulator. Arc is an abbreviateion for Anoxic Redox Control system. Arc systems are instrumental in maintaining energy metabolism during transcription of bacteria. The ArcA response regulator looks at growth conditions and expresses genes to best suit the bacteria. The Arc B sensor kinase, which is a tripartite protein, is membrane bound and can autophosphorylate.

The gab operon is responsible for the conversion of γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) to succinate. The gab operon comprises three structural genes – gabD, gabT and gabP – that encode for a succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, GABA transaminase and a GABA permease respectively. There is a regulatory gene csiR, downstream of the operon, that codes for a putative transcriptional repressor and is activated when nitrogen is limiting.

Methylomonas scandinavica is a species of Gram-negative gammaproteobacteria found in deep igneous rock ground water in Sweden. As a member of the Methylomonas genus, M. scandinavica has the ability to use methane as a carbon source.

Deinococcus frigens is a species of low temperature and drought-tolerating, UV-resistant bacteria from Antarctica. It is Gram-positive, non-motile and coccoid-shaped. Its type strain is AA-692. Individual Deinococcus frigens range in size from 0.9-2.0 μm and colonies appear orange or pink in color. Liquid-grown cells viewed using phase-contrast light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy on agar-coated slides show that isolated D. frigens appear to produce buds. Comparison of the genomes of Deiococcus radiodurans and D. frigens have predicted that no flagellar assembly exists in D. frigens.

Deinococcus marmoris is a Gram-positive bacterium isolated from Antarctica. As a species of the genus Deinococcus, the bacterium is UV-tolerant and able to withstand low temperatures.

Dokdonia is a genus of bacteria in the family Flavobacteriaceae and phylum Bacteroidota.

Actinobacillus equuli is a gram-negative, non-motile rod bacteria from the family Pasteurellaceae.

References

- 1 2 3 Trujillo, ME; Dedysh, S; DeVos, P; Hedlund, B; Kämpfer, P; Rainey, FA; Whitman, WB (2015). Taylorella. In Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and bacteria.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schulman, Martin Lance; May, Catherine Edith; Keys, Bronwyn; Guthrie, Alan John (November 2013). ""Contagious equine metritis: Artificial reproduction changes the epidemiologic paradigm"". Veterinary Microbiology. 167 (1–2): 2–8. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.021. PMID 23332460.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sugimoto, C; Isayama, Y; Sakazaki, R; Kuramochi, S (1983). "Transfer of Haemophilus equigenitalis Taylor et al. 1978 to the genus Taylorella gen. nov. as Taylorella equigenitalis comb. nov". Curr Microbiology. 9 (3): 155–162. doi:10.1007/BF01567289. S2CID 34944309.

- ↑ Taylor, C.E.D; Rosenthal, R.O; Brown, D.F.J; Lapage, S.P; Hill, L.R; Legros, R.M (1978). "The causative organism of contagious equine metritis 1977: proposal for a new species to be known as Haemophilus equigenitalis". Equine Veterinary Journal. 10 (3): 136–144. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1978.tb02242.x. PMID 99302.

- 1 2 Jacob, ME (2013). "Chapter 20: Taylorella". In McVey, DS; Kennedy, S; Chengappa, MM (eds.). Veterinary microbiology (3rd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118650622.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hebert, L; Moumen, B; Pons, N; Duquesne, F; Breuil, M-F; Goux, D; Batto, J-M; Laugier, C; Renault, P; Petry, S (2012). "Genomic characterization of the Taylorella genus". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e29953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029953 . PMC 3250509 . PMID 22235352.

- ↑ Lindmark, DG; Jarroll, EL; Timoney, PJ; Shin, SJ (1982). "Energy metabolism of the contagious equine metritis bacterium". Infectious Immunology. 36 (2): 531–534. doi:10.1128/iai.36.2.531-534.1982. PMC 351260 . PMID 7085071.

- 1 2 "3.5.2". Chapter 3.5.2 Contagious Equine Metritis. OIE Terrestrial Manual. 2018. pp. 1253–1259.

- 1 2 Pitcher, RS; Watmough, NJ (2004). "The bacterial cytochrome cbb3 oxidases". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1655 (1665): 388–399. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.09.017. PMID 15100055.

- 1 2 Crowhurst, R; Simpson, D; Greenwood, R; Ellis, D (1979-05-19). "Contagious equine metritis". Veterinary Record. 104 (20): 465. doi:10.1136/vr.104.20.465. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 473560. S2CID 39214701.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Timoney, PJ (June 1996). "Contagious equine metritis". Comparative Immunology, Microbiology, and Infectious Diseases. 19 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1016/0147-9571(96)00005-7. ISSN 0147-9571. PMID 8800545.

- 1 2 Matsuda, Motoo; Moore, John E (December 2003). "Recent advances in molecular epidemiology and detection of Taylorella equigenitalis associated with contagious equine metritis (CEM)". Veterinary Microbiology. 97 (1–2): 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.08.001. PMID 14637043.

- 1 2 Duquesne, F; Pronost, S; Laugier, C; Petry, S (February 2007). "Identification of Taylorella equigenitalis responsible for contagious equine metritis in equine genital swabs by direct polymerase chain reaction". Research in Veterinary Science. 82 (1): 47–49. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.05.001. PMID 16806331.

- 1 2 Luddy, Stacy; Kutzler, Michelle Anne (September 2010). "Contagious Equine Metritis Within the United States: A Review of the 2008 Outbreak". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 30 (8): 393–400. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2010.07.006.

- ↑ Erdman, Matthew M; Creekmore, Lynn H; Fox, Patricia E; Pelzel, Angela M.; Porter-Spalding, Barbara A; Aalsburg, Alan M; Cox, Linda K; Morningstar-Shaw, Brenda R; Crom, Randall L (November 2011). ""Diagnostic and epidemiologic analysis of the 2008–2010 investigation of a multi-year outbreak of contagious equine metritis in the United States". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 101 (3–4): 219–228. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.05.015. PMID 21715032.