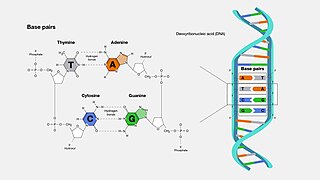

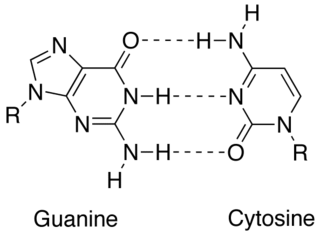

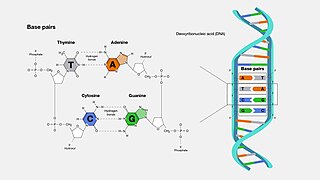

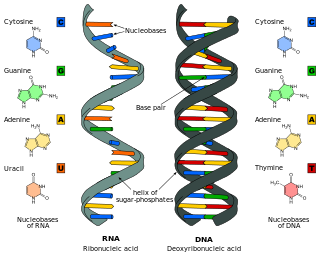

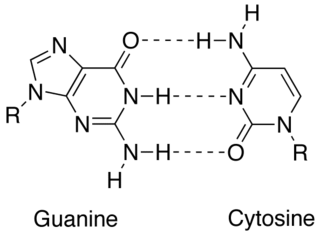

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" base pairs allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

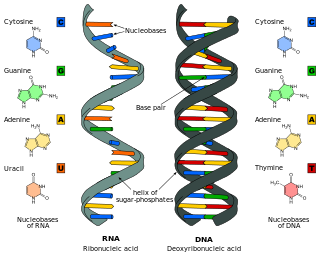

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself or by forming a template for production of proteins. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) are nucleic acids. The nucleic acids constitute one of the four major macromolecules essential for all known forms of life. RNA is assembled as a chain of nucleotides. Cellular organisms use messenger RNA (mRNA) to convey genetic information that directs synthesis of specific proteins. Many viruses encode their genetic information using an RNA genome.

Nucleobases are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nucleic acids. The ability of nucleobases to form base pairs and to stack one upon another leads directly to long-chain helical structures such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Five nucleobases—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and uracil (U)—are called primary or canonical. They function as the fundamental units of the genetic code, with the bases A, G, C, and T being found in DNA while A, G, C, and U are found in RNA. Thymine and uracil are distinguished by merely the presence or absence of a methyl group on the fifth carbon (C5) of these heterocyclic six-membered rings. In addition, some viruses have aminoadenine (Z) instead of adenine. It differs in having an extra amine group, creating a more stable bond to thymine.

In a chain-like biological molecule, such as a protein or nucleic acid, a structural motif is a common three-dimensional structure that appears in a variety of different, evolutionarily unrelated molecules. A structural motif does not have to be associated with a sequence motif; it can be represented by different and completely unrelated sequences in different proteins or RNA.

Stem-loop intramolecular base pairing is a pattern that can occur in single-stranded RNA. The structure is also known as a hairpin or hairpin loop. It occurs when two regions of the same strand, usually complementary in nucleotide sequence when read in opposite directions, base-pair to form a double helix that ends in an unpaired loop. The resulting structure is a key building block of many RNA secondary structures. As an important secondary structure of RNA, it can direct RNA folding, protect structural stability for messenger RNA (mRNA), provide recognition sites for RNA binding proteins, and serve as a substrate for enzymatic reactions.

In molecular biology, G-quadruplex secondary structures (G4) are formed in nucleic acids by sequences that are rich in guanine. They are helical in shape and contain guanine tetrads that can form from one, two or four strands. The unimolecular forms often occur naturally near the ends of the chromosomes, better known as the telomeric regions, and in transcriptional regulatory regions of multiple genes, both in microbes and across vertebrates including oncogenes in humans. Four guanine bases can associate through Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding to form a square planar structure called a guanine tetrad, and two or more guanine tetrads can stack on top of each other to form a G-quadruplex.

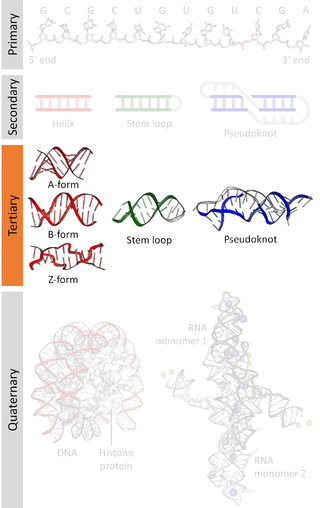

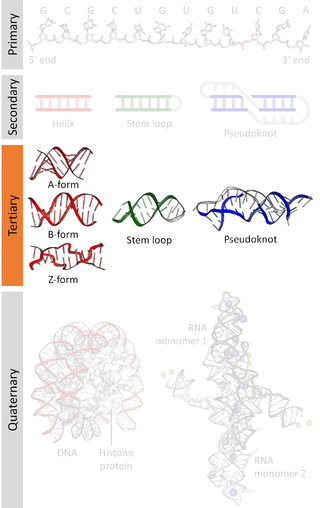

Biomolecular structure is the intricate folded, three-dimensional shape that is formed by a molecule of protein, DNA, or RNA, and that is important to its function. The structure of these molecules may be considered at any of several length scales ranging from the level of individual atoms to the relationships among entire protein subunits. This useful distinction among scales is often expressed as a decomposition of molecular structure into four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. The scaffold for this multiscale organization of the molecule arises at the secondary level, where the fundamental structural elements are the molecule's various hydrogen bonds. This leads to several recognizable domains of protein structure and nucleic acid structure, including such secondary-structure features as alpha helixes and beta sheets for proteins, and hairpin loops, bulges, and internal loops for nucleic acids. The terms primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure were introduced by Kaj Ulrik Linderstrøm-Lang in his 1951 Lane Medical Lectures at Stanford University.

Nucleic acid thermodynamics is the study of how temperature affects the nucleic acid structure of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA strands are in the random coil or single-stranded (ssDNA) state. Tm depends on the length of the DNA molecule and its specific nucleotide sequence. DNA, when in a state where its two strands are dissociated, is referred to as having been denatured by the high temperature.

A purine riboswitch is a sequence of ribonucleotides in certain messenger RNA (mRNA) that selectively binds to purine ligands via a natural aptamer domain. This binding causes a conformational change in the mRNA that can affect translation by revealing an expression platform for a downstream gene, or by forming a translation-terminating stem-loop. The ultimate effects of such translational regulation often take action to manage an abundance of the instigating purine, and might produce proteins that facilitate purine metabolism or purine membrane uptake.

Intrinsic, or rho-independent termination, is a process in prokaryotes to signal the end of transcription and release the newly constructed RNA molecule. In prokaryotes such as E. coli, transcription is terminated either by a rho-dependent process or rho-independent process. In the Rho-dependent process, the rho-protein locates and binds the signal sequence in the mRNA and signals for cleavage. Contrarily, intrinsic termination does not require a special protein to signal for termination and is controlled by the specific sequences of RNA. When the termination process begins, the transcribed mRNA forms a stable secondary structure hairpin loop, also known as a Stem-loop. This RNA hairpin is followed by multiple uracil nucleotides. The bonds between uracil and adenine are very weak. A protein bound to RNA polymerase (nusA) binds to the stem-loop structure tightly enough to cause the polymerase to temporarily stall. This pausing of the polymerase coincides with transcription of the poly-uracil sequence. The weak adenine-uracil bonds lower the energy of destabilization for the RNA-DNA duplex, allowing it to unwind and dissociate from the RNA polymerase. Overall, the modified RNA structure is what terminates transcription.

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered. Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain . Nucleic acid analogues are also called Xeno Nucleic Acid and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

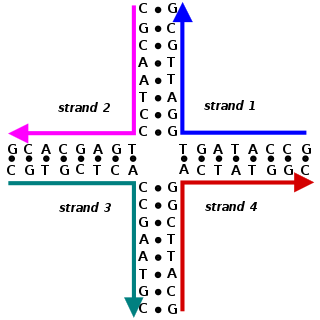

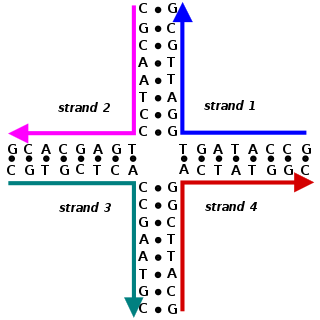

Nucleic acid design is the process of generating a set of nucleic acid base sequences that will associate into a desired conformation. Nucleic acid design is central to the fields of DNA nanotechnology and DNA computing. It is necessary because there are many possible sequences of nucleic acid strands that will fold into a given secondary structure, but many of these sequences will have undesired additional interactions which must be avoided. In addition, there are many tertiary structure considerations which affect the choice of a secondary structure for a given design.

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer. RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

The psaA RNA motif describes a class of RNAs with a common secondary structure. psaA RNAs are exclusively found in locations that presumably correspond to the 5' untranslated regions of operons formed of psaA and psaB genes. For this reason, it was hypothesized that psaA RNAs function as cis-regulatory elements of these genes. The psaAB genes encode proteins that form subunits in the photosystem I structure used for photosynthesis. psaA RNAs have been detected only in cyanobacteria, which is consistent with their association with photosynthesis.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

The 3' splice site of the influenza A virus segment 7 pre-mRNA can adopt two different types of RNA structure: a pseudoknot and a hairpin. This conformational switch is proposed to play a role in RNA alternative splicing and may influence the production of M1 and M2 proteins produced by splicing of this pre-mRNA.

Non-canonical base pairs are planar hydrogen bonded pairs of nucleobases, having hydrogen bonding patterns which differ from the patterns observed in Watson-Crick base pairs, as in the classic double helical DNA. The structures of polynucleotide strands of both DNA and RNA molecules can be understood in terms of sugar-phosphate backbones consisting of phosphodiester-linked D 2’ deoxyribofuranose sugar moieties, with purine or pyrimidine nucleobases covalently linked to them. Here, the N9 atoms of the purines, guanine and adenine, and the N1 atoms of the pyrimidines, cytosine and thymine, respectively, form glycosidic linkages with the C1’ atom of the sugars. These nucleobases can be schematically represented as triangles with one of their vertices linked to the sugar, and the three sides accounting for three edges through which they can form hydrogen bonds with other moieties, including with other nucleobases. The side opposite to the sugar linked vertex is traditionally called the Watson-Crick edge, since they are involved in forming the Watson-Crick base pairs which constitute building blocks of double helical DNA. The two sides adjacent to the sugar-linked vertex are referred to, respectively, as the Sugar and Hoogsteen edges.

In molecular biology, a guanine tetrad is a structure composed of four guanine bases in a square planar array. They most prominently contribute to the structure of G-quadruplexes, where their hydrogen bonding stabilizes the structure. Usually, there are at least two guanine tetrads in a G-quadruplex, and they often feature Hoogsteen-style hydrogen bonding.