Hydropower, also known as water power, is the use of falling or fast-running water to produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by converting the gravitational potential or kinetic energy of a water source to produce power. Hydropower is a method of sustainable energy production. Hydropower is now used principally for hydroelectric power generation, and is also applied as one half of an energy storage system known as pumped-storage hydroelectricity.

Tidal power or tidal energy is harnessed by converting energy from tides into useful forms of power, mainly electricity using various methods.

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower. Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and also more than nuclear power. Hydropower can provide large amounts of low-carbon electricity on demand, making it a key element for creating secure and clean electricity supply systems. A hydroelectric power station that has a dam and reservoir is a flexible source, since the amount of electricity produced can be increased or decreased in seconds or minutes in response to varying electricity demand. Once a hydroelectric complex is constructed, it produces no direct waste, and almost always emits considerably less greenhouse gas than fossil fuel-powered energy plants. However, when constructed in lowland rainforest areas, where part of the forest is inundated, substantial amounts of greenhouse gases may be emitted.

The Severn Estuary is the estuary of the River Severn, flowing into the Bristol Channel between South West England and South Wales. Its very high tidal range, approximately 50 feet (15 m), creates valuable intertidal habitats and has led to the area being at the centre of discussions in the UK regarding renewable tidal energy.

The Gandhi Sagar Dam is one of the four major dams built on India's Chambal River. The dam is located in the Mandsaur district of the state of Madhya Pradesh. It is a masonry gravity dam, standing 62.17 metres (204.0 ft) high, with a gross storage capacity of 7.322 billion cubic metres from a catchment area of 22,584 km2 (8,720 sq mi). The dam's foundation stone was laid by Prime Minister of India Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru on 7 March 1954, and construction of the main dam was done by leading contractor Dwarka Das Agrawal & Associates and was completed in 1960. Additional dam structures were completed downstream in the 1970s.

The Severn Barrage is any of a range of ideas for building a barrage from the English coast to the Welsh coast over the Severn tidal estuary. Ideas for damming or barraging the Severn estuary have existed since the 19th century. The building of such a barrage would constitute an engineering project comparable with some of the world's biggest. The purposes of such a project have typically been one or several of: transport links, flood protection, harbour creation, or tidal power generation. In recent decades it is the latter that has grown to be the primary focus for barrage ideas, and the others are now seen as useful side-effects. Following the Severn Tidal Power Feasibility Study (2008–10), the British government concluded that there was no strategic case for building a barrage but to continue to investigate emerging technologies. In June 2013 the Energy and Climate Change Select Committee published its findings after an eight-month study of the arguments for and against the Barrage. MPs said the case for the barrage was unproven. They were not convinced the economic case was strong enough and said the developer, Hafren Power, had failed to answer serious environmental and economic concerns.

A tide mill is a water mill driven by tidal rise and fall. A dam with a sluice is created across a suitable tidal inlet, or a section of river estuary is made into a reservoir. As the tide comes in, it enters the mill pond through a one-way gate, and this gate closes automatically when the tide begins to fall. When the tide is low enough, the stored water can be released to turn a water wheel.

The Rance Tidal Power Station is a tidal power station located on the estuary of the Rance River in Brittany, France.

The Annapolis Royal Generating Station was a tidal power generating station in the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, Canada. When operational, it was the only tidal generating station in North America and was one of the few in the world. Located upstream of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, it generated about 30 million kilowatt hours per year, enough for 4500 houses. Peak output was 20 megawatts.

Run-of-river hydroelectricity (ROR) or run-of-the-river hydroelectricity is a type of hydroelectric generation plant whereby little or no water storage is provided. Run-of-the-river power plants may have no water storage at all or a limited amount of storage, in which case the storage reservoir is referred to as pondage. A plant without pondage is subject to seasonal river flows, so the plant will operate as an intermittent energy source. Conventional hydro uses reservoirs, which regulate water for flood control, dispatchable electrical power, and the provision of fresh water for agriculture.

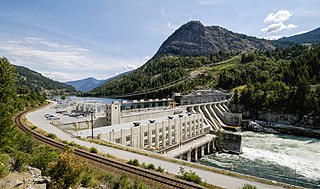

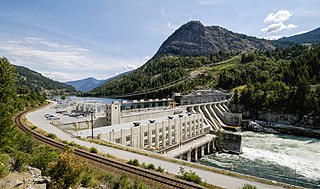

Brilliant Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the Kootenay River near Castlegar, British Columbia, Canada. It was built during the Second World War, mostly by Doukhobour men exempt from military service, and its 129 MW twin turbines first came into operation in June, 1944. The Columbia Power Corporation purchased the dam from Teck Cominco in 1996.

Marine Current Turbines Ltd (MCT), was a United Kingdom-based company that developed tidal stream generators, most notably the 1.2 MW SeaGen turbine. The company was bought by the German automation company, Siemens in 2012, who later sold the company to Atlantis Resources in 2015.

Severn Tidal Power Feasibility Study is the name of a UK Government feasibility study into a tidal power project looking at the possibility of using the huge tidal range in the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel to generate electricity.

New Zealand has large ocean energy resources but does not yet generate any power from them. TVNZ reported in 2007 that over 20 wave and tidal power projects are currently under development. However, not a lot of public information is available about these projects. The Aotearoa Wave and Tidal Energy Association was established in 2006 to "promote the uptake of marine energy in New Zealand". According to their 10 February 2008 newsletter, they have 59 members. However, the association doesn't list its members.

Low-head hydro power refers to the development of hydroelectric power where the head is typically less than 20 metres, although precise definitions vary. Head is the vertical height measured between the hydro intake water level and the water level at the point of discharge. Using only a low head drop in a river or tidal flows to create electricity may provide a renewable energy source that will have a minimal impact on the environment. Since the generated power is a function of the head these systems are typically classed as small-scale hydropower, which have an installed capacity of less than 5MW.

Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station is the world's largest tidal power installation, with a total power output capacity of 254 MW. When completed in 2011, it surpassed France's 240 MW Rance Tidal Power Station, which was the world's largest for 45 years. It is operated by the Korea Water Resources Corporation.

A tidal farm is a group of tidal stream generators used for production of electric power. The potential of tidal farms is limited by the number of suitable sites across the globe as there are niche requirements to make a tidal farm cost effective and environmentally conscious.

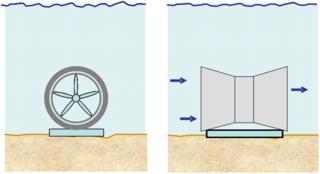

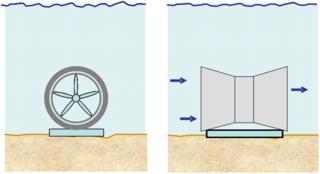

A tidal stream generator, often referred to as a tidal energy converter (TEC), is a machine that extracts energy from moving masses of water, in particular tides, although the term is often used in reference to machines designed to extract energy from the run of a river or tidal estuarine sites. Certain types of these machines function very much like underwater wind turbines and are thus often referred to as tidal turbines. They were first conceived in the 1970s during the oil crisis.

A barrage is a type of low-head, diversion dam which consists of a number of large gates that can be opened or closed to control the amount of water passing through. This allows the structure to regulate and stabilize river water elevation upstream for use in irrigation and other systems. The gates are set between flanking piers which are responsible for supporting the water load of the pool created.

The water wall turbine is a water turbine designed to utilize hydrostatic pressure differences for low head hydropower generation. It supports bidirectional inflow operation using radial blades that rotate around a horizontal axis. The water wall turbine is suitable for energy extraction from tidal and freshwater currents. For tidal power installations, the turbine operates in both directions as the tide ebbs and flows.