Contents

- Synopsis

- History

- Background

- Publication

- Critical analysis

- Adaptations and exhibitions

- References

- Footnotes

- Bibliography

- External links

| Tintin and Alph-Art (Tintin et l'Alph-Art) | |

|---|---|

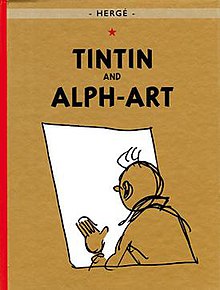

Cover of the English-language edition (2004 edition) | |

| Date | 1986 |

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Egmont/Sundancer |

| Date | 1990 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Tintin and the Picaros (1976) |

Tintin and Alph-Art (French: Tintin et l'Alph-Art) is the unfinished twenty-fourth and final volume of The Adventures of Tintin , the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Left incomplete on Hergé's death, the manuscript was posthumously published in 1986. The story revolves around Brussels' modern art scene, where the young reporter Tintin discovers that a local art dealer has been murdered. Investigating further, he encounters a conspiracy of art forgery, masterminded by a religious teacher named Endaddine Akass.

Reflecting his own fascination for modern art, Hergé began work on Tintin and Alph-Art in 1978. However, it was left unfinished at the time of his death in March 1983. At this point it consisted of around 150 pages of pencil-drawn notes, outlines and sketches – not yet rendered in Hergé's trademark ligne claire drawing style – with no ending having been devised for the story. Hergé's colleague Bob de Moor offered to complete the story for publication, and while Hergé's widow Fanny Vlamynck initially agreed, she changed her decision, citing the fact that her late husband had not wanted anyone else to continue The Adventures of Tintin.

A selection of the original notes were collected together and published in book form by Casterman in 1986. Since that point, several other cartoonists, such as Yves Rodier, have produced their own finished, unauthorized versions of the story. Critical reception of the work has been mixed; some commentators on The Adventures of Tintin believe that if Tintin and Alph-Art had been completed, it would have been an improvement over the previous two volumes, while others have characterised such assessments as wishful thinking.