Georges Prosper Remi, known by the pen name Hergé, from the French pronunciation of his reversed initials RG, was a Belgian comic strip artist. He is best known for creating The Adventures of Tintin, the series of comic albums which are considered one of the most popular European comics of the 20th century. He was also responsible for two other well-known series, Quick & Flupke (1930–1940) and The Adventures of Jo, Zette and Jocko (1936–1957). His works were executed in his distinctive ligne claire drawing style.

Cigars of the Pharaoh is the fourth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the series of comic albums by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from December 1932 to February 1934. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who are travelling in Egypt when they discover a pharaoh's tomb with dead Egyptologists and boxes of cigars. Pursuing the mystery of the cigars, Tintin and Snowy travel across Southern Arabia and India, and reveal the secrets of an international drug smuggling enterprise.

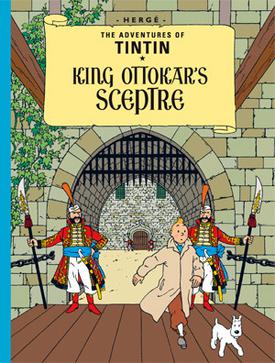

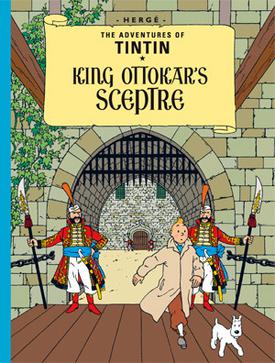

King Ottokar's Sceptre is the eighth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from August 1938 to August 1939. Hergé intended the story as a satirical criticism of the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, in particular the annexation of Austria in March 1938. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who travel to the fictional Balkan nation of Syldavia, where they combat a plot to overthrow the monarchy of King Muskar XII.

The Red Sea Sharks is the nineteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comic series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was initially serialised weekly in Belgium's Tintin magazine from October 1956 to January 1958 before being published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1958. The narrative follows the young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and his friend Captain Haddock as they travel to the fictional Middle Eastern kingdom of Khemed with the intention of aiding the Emir Ben Kalish Ezab in regaining control after a coup d'état by his enemies, who are financed by slave traders led by Tintin's old nemesis Rastapopoulos.

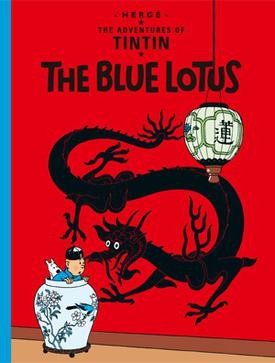

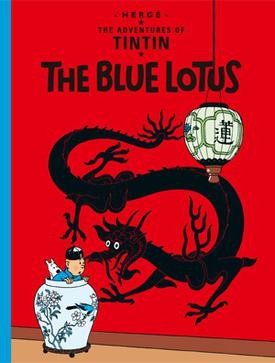

The Blue Lotus is the fifth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from August 1934 to October 1935 before being published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1936. Continuing where the plot of the previous story, Cigars of the Pharaoh, left off, the story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who are invited to China in the middle of the 1931 Japanese invasion, where Tintin reveals the machinations of Japanese spies and uncovers a drug-smuggling ring.

Tintin in America is the third volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialized weekly from September 1931 to October 1932 before being published in a collected volume by Éditions du Petit Vingtième in 1932. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy who travel to the United States, where Tintin reports on organized crime in Chicago. Pursuing a gangster across the country, he encounters a tribe of Blackfoot Native Americans before defeating the Chicago crime syndicate.

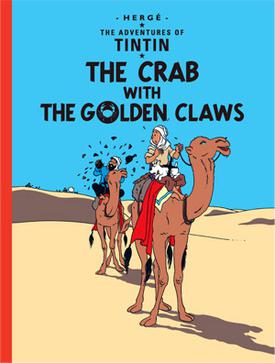

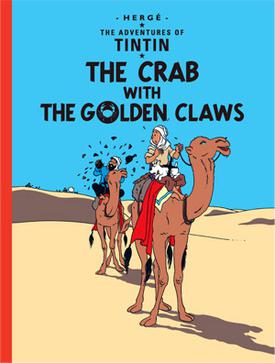

The Crab with the Golden Claws is the ninth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised weekly in Le Soir Jeunesse, the children's supplement to Le Soir, Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from October 1940 to October 1941 amidst the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Partway through serialisation, Le Soir Jeunesse was cancelled and the story began to be serialised daily in the pages of Le Soir. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who travel to Morocco to pursue the international opium smugglers. The story marks the first appearance of main character Captain Haddock.

Tintin in Tibet is the twentieth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. It was serialised weekly from September 1958 to November 1959 in Tintin magazine and published as a book in 1960. Hergé considered it his favourite Tintin adventure and an emotional effort, as he created it while suffering from traumatic nightmares and a personal conflict while deciding to leave his wife of three decades for a younger woman. The story tells of the young reporter Tintin in search of his friend Chang Chong-Chen, who the authorities claim has died in a plane crash in the Himalayas. Convinced that Chang has survived and accompanied only by Snowy, Captain Haddock and the Sherpa guide Tharkey, Tintin crosses the Himalayas to the plateau of Tibet, along the way encountering the mysterious Yeti.

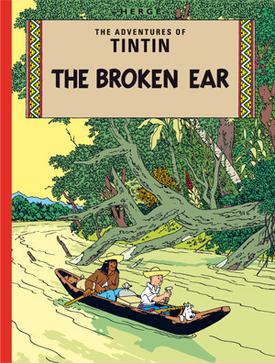

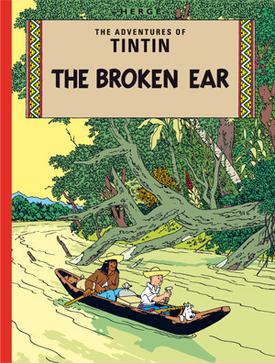

The Broken Ear is the sixth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from December 1935 to February 1937. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, as he searches for a stolen South American fetish, identifiable by its broken right ear, and deals with other thieves who are after it. In doing so, he ends up in the fictional nation of San Theodoros, where he becomes embroiled in a war and discovers the Arumbaya tribe deep in the forest.

Tintin in the Congo is the second volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian comic strip artist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from May 1930 to June 1931 before being published in a collected volume by Éditions de Petit Vingtième in 1931. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who are sent to the Belgian Congo to report on events in the country. Amid various encounters with the native Congolese people and wild animals, Tintin unearths a criminal diamond smuggling operation run by the American gangster Al Capone.

The Black Island is the seventh volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from April to November 1937. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who travel to England in pursuit of a gang of counterfeiters. Framed for theft and hunted by detectives Thomson and Thompson, Tintin follows the criminals to Scotland, discovering their lair on the Black Island.

The Secret of the Unicorn is the eleventh volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in Le Soir, Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from June 1942 to January 1943 amidst the Nazi German occupation of Belgium during World War II. The story revolves around young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and his friend Captain Haddock, who discover a riddle left by Haddock's ancestor, the 17th century Sir Francis Haddock, which can lead them to the hidden treasure of the pirate Red Rackham. To unravel the riddle, Tintin and Haddock must obtain three identical models of Sir Francis's ship, the Unicorn, but they discover that criminals are also after three model ships and are willing to kill in order to obtain them.

Red Rackham's Treasure is the twelfth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in Le Soir, Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from February to September 1943 amidst the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Completing an arc begun in The Secret of the Unicorn, the story tells of young reporter Tintin and his friend Captain Haddock as they launch an expedition to the Caribbean to locate the treasure of the pirate Red Rackham.

The Seven Crystal Balls is the thirteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in Le Soir, Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from December 1943 amidst the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. The story was cancelled abruptly following the Allied liberation in September 1944, when Hergé was blacklisted after being accused of collaborating with the occupying Germans. After he was cleared two years later, the story and its follow-up Prisoners of the Sun were then serialised weekly in the new Tintin magazine from September 1946 to April 1948. The story revolves around the investigations of a young reporter Tintin and his friend Captain Haddock into the abduction of their friend Professor Calculus and its connection to a mysterious illness which has afflicted the members of an archaeological expedition to Peru.

Prisoners of the Sun is the fourteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised weekly in the newly established Tintin magazine from September 1946 to April 1948. Completing an arc begun in The Seven Crystal Balls, the story tells of young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and friend Captain Haddock as they continue their efforts to rescue the kidnapped Professor Calculus by travelling through Andean villages, mountains, and rain forests, before finding a hidden Inca civilisation.

Land of Black Gold is the fifteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, in which it was initially serialised from September 1939 until the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940, at which the newspaper was shut down and the story interrupted. After eight years, Hergé returned to Land of Black Gold, completing its serialisation in Belgium's Tintin magazine from September 1948 to February 1950, after which it was published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1950. Set on the eve of a European war, the plot revolves around the attempts of young Belgian reporter Tintin to uncover a militant group responsible for sabotaging oil supplies in the Middle East.

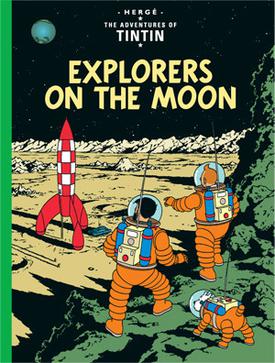

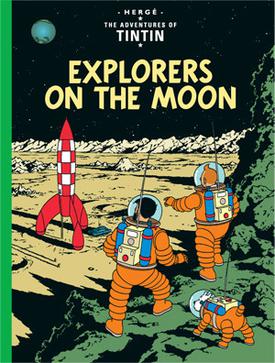

Explorers on the Moon is the seventeenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised weekly in Belgium's Tintin magazine from October 1952 to December 1953 before being published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1954. Completing a story arc begun in the preceding volume, Destination Moon (1953), the narrative tells of the young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and friends Captain Haddock, Professor Calculus, and Thomson and Thompson who are aboard humanity's first crewed rocket mission to the Moon.

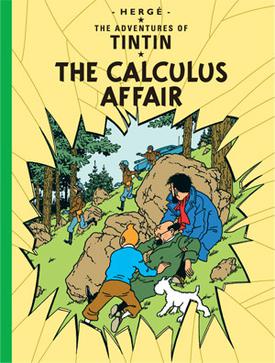

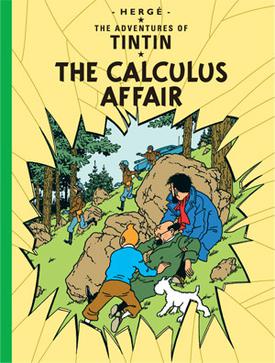

The Calculus Affair is the eighteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé. It was serialised weekly in Belgium's Tintin magazine from December 1954 to February 1956 before being published in a single volume by Casterman in 1956. The story follows the attempts of the young reporter Tintin, his dog Snowy, and his friend Captain Haddock to rescue their friend Professor Calculus, who has developed a machine capable of destroying objects with sound waves, from kidnapping attempts by the competing European countries of Borduria and Syldavia.

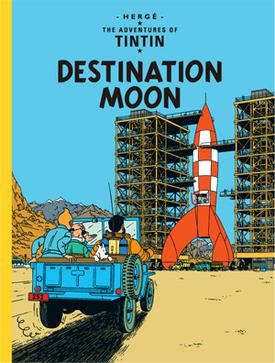

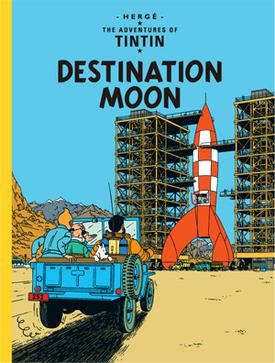

Destination Moon is the sixteenth volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was initially serialised weekly in Belgium's Tintin magazine from March to September 1950 and April to October 1952 before being published in a collected volume by Casterman in 1953. The plot tells of young reporter Tintin and his friend Captain Haddock who receive an invitation from Professor Calculus to come to Syldavia, where Calculus is working on a top-secret project in a secure government facility to plan a crewed mission to the Moon.

The Adventures of Totor, Chief Scout of the Cockchafers is the first comic strip series by the Belgian cartoonist and author Hergé, who later came to notability as the author of The Adventures of Tintin series. It was serialised monthly from July 1926 to summer 1929 in Belgian scouting magazine Le Boy Scout Belge, with a nine month break in 1927. The plot synopsis revolved around the eponymous Totor, a Belgian boy scout who travels to visit his aunt and uncle in Texas, United States. Once there, he comes across hostile Native American tribes and gangsters, each of whom he outwits, before returning to Belgium.