Say–Meyer syndrome is a rare X-linked genetic disorder that is mostly characterized as developmental delay. It is one of the rare causes of short stature. It is closely related with trigonocephaly. People with Say–Meyer syndrome have impaired growth, deficits in motor skills development and mental state.

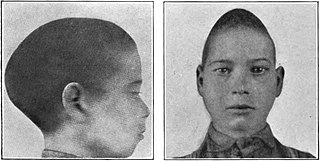

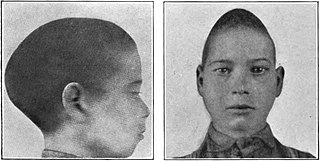

Scaphocephaly, or sagittal craniosynostosis, is a type of cephalic disorder which occurs when there is a premature fusion of the sagittal suture. Premature closure results in limited lateral expansion of the skull resulting in a characteristic long, narrow head. The skull base is typically spared.

Rhinoplasty, commonly called nose job, medically called nasal reconstruction is a plastic surgery procedure for altering and reconstructing the nose. There are two types of plastic surgery used – reconstructive surgery that restores the form and functions of the nose and cosmetic surgery that changes the appearance of the nose. Reconstructive surgery seeks to resolve nasal injuries caused by various traumas including blunt, and penetrating trauma and trauma caused by blast injury. Reconstructive surgery can also treat birth defects, breathing problems, and failed primary rhinoplasties. Rhinoplasty may remove a bump, narrow nostril width, change the angle between the nose and the mouth, or address injuries, birth defects, or other problems that affect breathing, such as a deviated nasal septum or a sinus condition. Surgery only on the septum is called a septoplasty.

Oral and maxillofacial surgery is a surgical specialty focusing on reconstructive surgery of the face, facial trauma surgery, the oral cavity, head and neck, mouth, and jaws, as well as facial cosmetic surgery/facial plastic surgery including cleft lip and cleft palate surgery.

Crouzon syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder known as a branchial arch syndrome. Specifically, this syndrome affects the first branchial arch, which is the precursor of the maxilla and mandible. Since the branchial arches are important developmental features in a growing embryo, disturbances in their development create lasting and widespread effects.

Apert syndrome is a form of acrocephalosyndactyly, a congenital disorder characterized by malformations of the skull, face, hands and feet. It is classified as a branchial arch syndrome, affecting the first branchial arch, the precursor of the maxilla and mandible. Disturbances in the development of the branchial arches in fetal development create lasting and widespread effects.

Craniosynostosis is a condition in which one or more of the fibrous sutures in a young infant's skull prematurely fuses by turning into bone (ossification), thereby changing the growth pattern of the skull. Because the skull cannot expand perpendicular to the fused suture, it compensates by growing more in the direction parallel to the closed sutures. Sometimes the resulting growth pattern provides the necessary space for the growing brain, but results in an abnormal head shape and abnormal facial features. In cases in which the compensation does not effectively provide enough space for the growing brain, craniosynostosis results in increased intracranial pressure leading possibly to visual impairment, sleeping impairment, eating difficulties, or an impairment of mental development combined with a significant reduction in IQ.

Microtia is a congenital deformity where the auricle is underdeveloped. A completely undeveloped pinna is referred to as anotia. Because microtia and anotia have the same origin, it can be referred to as microtia-anotia. Microtia can be unilateral or bilateral. Microtia occurs in 1 out of about 8,000–10,000 births. In unilateral microtia, the right ear is most commonly affected. It may occur as a complication of taking Accutane (isotretinoin) during pregnancy.

Craniofacial surgery is a surgical subspecialty that deals with congenital and acquired deformities of the head, skull, face, neck, jaws and associated structures. Although craniofacial treatment often involves manipulation of bone, craniofacial surgery is not tissue-specific; craniofacial surgeons deal with bone, skin, nerve, muscle, teeth, and other related anatomy.

The frontal suture is a fibrous joint that divides the two halves of the frontal bone of the skull in infants and children. Typically, it completely fuses between three and nine months of age, with the two halves of the frontal bone being fused together. It is also called the metopic suture, although this term may also refer specifically to a persistent frontal suture.

Acrocephalosyndactyly is a group of congenital conditions characterized by irregular features of the face and skull (craniosynostosis) and hands and feet (syndactyly). Craniosynostosis occurs when the cranial sutures, the fibrous tissue connecting the skull bones, fuse the cranial bones early in development. Cranial sutures allow the skull bones to continue growing until they fuse at age 24. Premature fusing of the cranial sutures can result in alterations to the skull shape and interfere with brain growth. Syndactyly occurs when digits of the hands or feet are fused together. When polydactyly is also present, the classification is acrocephalopolysyndactyly. Polydactyly occurs when the hands or feet possess additional digits. Acrocephalosyndactyly is usually diagnosed after birth, although prenatal diagnosis is sometimes possible if the genetic variation is present in family members, as the conditions are typically inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern Treatment often involves surgery in early childhood to correct for craniosynostosis and syndactyly.

Migraine surgery is a surgical operation undertaken with the goal of reducing or preventing migraines. Migraine surgery most often refers to surgical nerve decompression of one or several nerves in the head and neck which have been shown to trigger migraine symptoms in many migraine sufferers. Following the development of nerve decompression techniques for the relief of migraine pain in the year 2000, these procedures have been extensively studied and shown to be effective in appropriate candidates. The nerves that are most often addressed in migraine surgery are found outside of the skull, in the face and neck, and include the supra-orbital and supra-trochlear nerves in the forehead, the zygomaticotemporal nerve and auriculotemporal nerves in the temple region, and the greater occipital, lesser occipital, and third occipital nerves in the back of the neck. Nerve impingement in the nasal cavity has additionally been shown to be a trigger of migraine symptoms.

Frontonasal dysplasia (FND) is a congenital malformation of the midface. For the diagnosis of FND, a patient should present at least two of the following characteristics: hypertelorism, a wide nasal root, vertical midline cleft of the nose and/or upper lip, cleft of the wings of the nose, malformed nasal tip, encephalocele or V-shaped hair pattern on the forehead. The cause of FND remains unknown. FND seems to be sporadic (random) and multiple environmental factors are suggested as possible causes for the syndrome. However, in some families multiple cases of FND were reported, which suggests a genetic cause of FND.

Karin Marie Muraszko is an American pediatric neurosurgeon.

A facial cleft is an opening or gap in the face, or a malformation of a part of the face. Facial clefts is a collective term for all sorts of clefts. All structures like bone, soft tissue, skin etc. can be affected. Facial clefts are extremely rare congenital anomalies. There are many variations of a type of clefting and classifications are needed to describe and classify all types of clefting. Facial clefts hardly ever occur isolated; most of the time there is an overlap of adjacent facial clefts.

McGillivray syndrome is a rare syndrome characterized mainly by heart defects, skull and facial abnormalities and ambiguous genitalia. The symptoms of this syndrome are ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, small jaw, undescended testes, and webbed fingers. Beside to these symptoms there are more symptoms which is related with bone structure and misshape.

Carpal tunnel surgery, also called carpal tunnel release (CTR) and carpal tunnel decompression surgery, is a nerve decompression in which the transverse carpal ligament is divided. It is a surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and recommended when there is constant (not just intermittent) numbness, muscle weakness, or atrophy, and when night-splinting no longer controls intermittent symptoms of pain in the carpal tunnel. In general, milder cases can be controlled for months to years, but severe cases are unrelenting symptomatically and are likely to result in surgical treatment. Approximately 500,000 surgical procedures are performed each year, and the economic impact of this condition is estimated to exceed $2 billion annually.

Metopism is the condition of having a persistent metopic suture, or persistence of the frontal metopic suture in the adult human skull. Metopism is the opposite of craniosynostosis. The main factor of the metopic suture is to increase the volume of the anterior cranial fossa. The frontal bone includes the forehead, and the roofs of the orbits of the eyes. The frontal bone has vertical portion (squama) and horizontal portion. Some adults have a metopic or frontal suture in the vertical portion. In uterine period in right and left half of frontal region of the fetus there is a membrane tissue. On each half a primary ossification center appears about the end of the second month of the fetus. Primary ossification center extends to form the corresponding half of the vertical part (squama) and horizontal part of the frontal bone.

Neuroplastic or neuroplastic and reconstructive surgery is the surgical specialty involved in reconstruction or restoration of patients who undergo surgery of the central or peripheral nervous system. The field includes a wide variety of surgical procedures that seek to restore or replace a patient's skull, face, scalp, dura, the spine and/or its overlying tissues.

Leptocephaly is a rare form of complex craniosynostosis in which the sagittal and metopic suture simultaneously close. Leptocephaly is characterized by equal narrowing of the head and a tall and narrow head shape. Leptocephaly is usually nonsyndromic, but has been seen in individual cases such as Neu-Laxova syndrome.