Article One of the United States Constitution establishes the legislative branch of the federal government, the United States Congress. Under Article One, Congress is a bicameral legislature consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Article One grants Congress various enumerated powers and the ability to pass laws "necessary and proper" to carry out those powers. Article One also establishes the procedures for passing a bill and places various limits on the powers of Congress and the states from abusing their powers.

The Tenure of Office Act was a United States federal law, in force from 1867 to 1887, that was intended to restrict the power of the president to remove certain office-holders without the approval of the U.S. Senate. The law was enacted March 2, 1867, over the veto of President Andrew Johnson. It purported to deny the president the power to remove any executive officer who had been appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, unless the Senate approved the removal during the next full session of Congress.

The Congress of the Philippines is the legislature of the national government of the Philippines. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, although colloquially the term "Congress" commonly refers to just the latter, and an upper body, the Senate. The House of Representatives meets in the Batasang Pambansa in Quezon City while the Senate meets in the GSIS Building in Pasay.

John Covode was an American businessman and abolitionist politician. He served three terms in the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

The Corwin Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that has never been adopted, but owing to the absence of a ratification deadline, could still be adopted by the state legislatures. It would shield slavery within the states from the federal constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress. Although the Corwin Amendment does not explicitly use the word slavery, it was designed specifically to protect slavery from federal power. The outgoing 36th United States Congress proposed the Corwin Amendment on March 2, 1861, shortly before the outbreak of the American Civil War, with the intent of preventing that war and preserving the Union. It passed Congress but was not ratified by the requisite number of state legislatures.

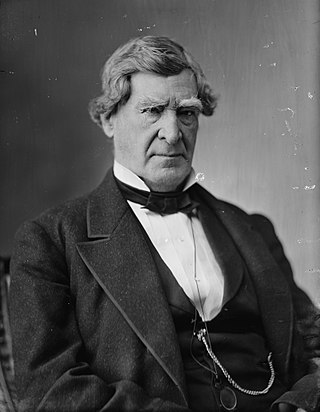

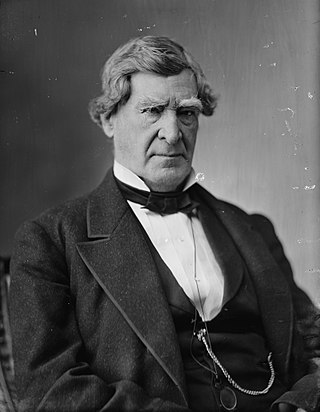

Jeremiah Sullivan Black was an American statesman and lawyer. He served as a justice on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (1851–1857) and as the Court's Chief Justice (1851–1854). He also served in the Cabinet of President James Buchanan, first as Attorney General (1857–1860), and then Secretary of State (1860–1861).

Impeachment in the Philippines is an expressed power of the Congress of the Philippines to formally charge a serving government official with an impeachable offense. After being impeached by the House of Representatives, the official is then tried in the Senate. If convicted, the official is either removed from office or censured.

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson was initiated on February 24, 1868, when the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution to impeach Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, for "high crimes and misdemeanors". The alleged high crimes and misdemeanors were afterwards specified in eleven articles of impeachment adopted by the House on March 2 and 3, 1868. The primary charge against Johnson was that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act. Specifically, that he had acted to remove from office Edwin Stanton and to replace him with Brevet Major General Lorenzo Thomas as secretary of war ad interim. The Tenure of Office had been passed by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto with the primary intent of protecting Stanton from being fired without the Senate's consent. Stanton often sided with the Radical Republican faction and did not have a good relationship with Johnson.

An Act to protect the commerce of the United States and punish the crime of piracy is an 1819 United States federal statute against piracy, amended in 1820 to declare participating in the slave trade or robbing a ship to be piracy as well. The last execution for piracy in the United States was of slave trader Nathaniel Gordon in 1862 in New York, under the amended act.

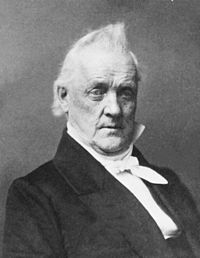

James Buchanan Jr. was an American lawyer, diplomat, and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvania in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He was an advocate for states' rights, particularly regarding slavery, and minimized the role of the federal government preceding the Civil War. Buchanan was the last president born in the 18th century.

During his presidency, Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, saw multiple efforts during his presidency to impeach him, culminating in his formal impeachment on February 24, 1868, which was followed by a Senate impeachment trial in which he was acquitted.

The first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson was launched by a vote of the United States House of Representatives on January 7, 1867 to investigate the potential impeachment of the President of the United States, Andrew Johnson. It was run by the House Committee on the Judiciary.

The second impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson was an impeachment inquiry against United States President Andrew Johnson. It followed a previous inquiry in 1867. The second inquiry, unlike the first, was run by the House Select Committee on Reconstruction. The second inquiry ran from its authorization on January 27, 1868 until the House Select Committee on Reconstruction reported to Congress on February 22, 1868.

The House Select Committee on Reconstruction was a select committee which existed the United States House of Representatives during the 40th and 41st Congresses with a focus related to the Reconstruction Acts. The 39th Congress had had a similar joint committee called the United States Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction.

In the United States, an impeachment inquiry is an investigation or inquiry which usually occurs before a potential impeachment vote.

Andrew Johnson became the first president of the United States to be impeached by the United States House of Representatives on February 24, 1868 after he acted to dismiss Edwin Stanton as secretary of war in disregard for the Tenure of Office Act.

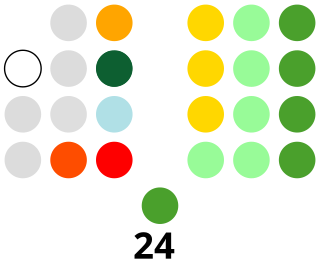

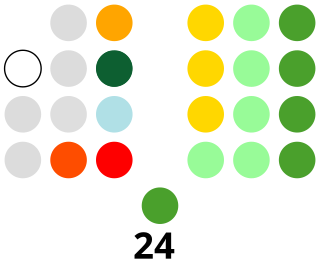

Eleven articles of impeachment against United States President Andrew Johnson were adopted by the United States House of Representatives on March 2 and 3, 1868 as part of the impeachment of Johnson. An impeachment resolution had previously been adopted by the House on February 24, 1868. Each of the articles were a separate charge which Johnson would be tried for in his subsequent impeachment trial before the United States Senate.

In the United States, federal impeachment is the process by which the House of Representatives charges the president, vice president, or a civil federal officer for alleged misconduct. The House can impeach an individual with a simple majority of the present members or other criteria adopted by the House according to Article One, Section 2, Clause 5 of the U.S. Constitution. Similarly, state and territorial officials, such as a governor, can be impeached and tried by their respective legislatures according to their constitutions. In Washington, D.C., elected officials, except the District's delegate to the Congress, are removed in a recall election instead of through an impeachment process.