The Bolivarian National Intelligence Service is the premier intelligence agency in Venezuela. SEBIN is an internal security force subordinate to the Vice President of Venezuela since 2012 and is dependent on Vice President Delcy Rodríguez. SEBIN has been described as the political police force of the Bolivarian government.

Tareck Zaidan El Aissami Maddah is a Venezuelan politician, who served as the vice president of Venezuela from 2017 to 2018. He served as Minister of Industries and National Production since 14 June 2018, and as Minister of Petroleum from 27 April 2020 until 20 March 2023. He previously was Minister of the Interior and Justice from 2008 to 2012, Governor of Aragua from 2012 to 2017, and the vice president of Venezuela from 2017 to 2018. While holding that office, El Aissami faced allegations of participating in corruption, money laundering and drug trafficking. In 2019, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) added El Aissami to the ICE Most Wanted List, listed by the Homeland Security Investigations unit. El Aissami, who was among the power brokers in Nicolás Maduro's government, resigned on 20 March 2023 during a corruption probe. He was arrested by the Venezuelan prosecutor's office on charges of treason, money laundering and criminal association.

The level of corruption in Venezuela is very high by world standards and is prevalent throughout many levels of Venezuelan society. Discovery of oil in Venezuela in the early 20th century has worsened political corruption. The large amount of corruption and mismanagement in the country has resulted in severe economic difficulties, part of the crisis in Venezuela. A 2014 Gallup poll found that 75% of Venezuelans believed that corruption was widespread throughout the Venezuelan government. Discontent with corruption was cited by demonstrators as one of the reasons for the 2014 and 2017 Venezuelan protests.

The Bolivarian Militia of Venezuela, is a militia branch of the National Bolivarian Armed Forces of Venezuela. Its headquarters is at the National Military Museum, Fort Montana, Caracas. The Commanding General of the National Militia is Major General Carlos Augusto Leal Tellería, Venezuelan Army, as of March 2018. The National Militia celebrates its anniversary every April 13 yearly.

Crime in Venezuela is widespread, with violent crimes such as murder and kidnapping increasing for several years. In 2014, the United Nations attributed crime to the poor political and economic environment in the country—which, at the time, had the second highest murder rate in the world. Rates of crime rapidly began to increase during the presidency of Hugo Chávez due to the institutional instability of his Bolivarian government, underfunding of police resources, and severe inequality. Chávez's government sought a cultural hegemony by promoting class conflict and social fragmentation, which in turn encouraged "criminal gangs to kill, kidnap, rob and extort". Upon Chávez's death in 2013, Venezuela was ranked the most insecure nation in the world by Gallup.

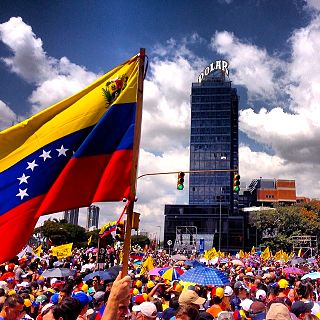

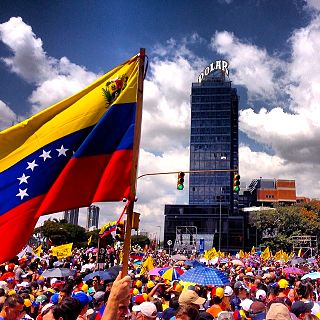

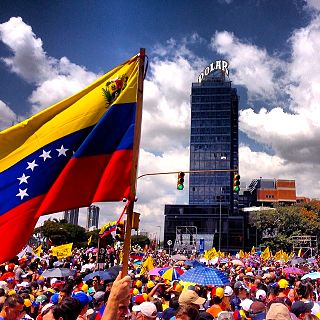

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods and services. Explanations for these worsening conditions vary, with analysis blaming strict price controls, alongside long-term, widespread political corruption resulting in the under-funding of basic government services. While protests first occurred in January, after the murder of actress and former Miss Venezuela Mónica Spear, the 2014 protests against Nicolás Maduro began in earnest that February following the attempted rape of a student on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests and killings of student protesters spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders. The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protesters and government forces that resulted in nearly 4,000 arrests and 43 deaths, including both supporters and opponents of the government. Toward the end of 2014, and into 2015, continued shortages and low oil prices caused renewed protesting.

Colectivos are far-left Venezuelan armed paramilitary groups that support the Bolivarian government, the Great Patriotic Pole (GPP) political alliance and Venezuela's ruling party, and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Colectivo has become an umbrella term for irregular armed groups that operate in poverty-stricken areas.

The 2014 Venezuelan protests began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created the Venezuelan government. The protests have lasted for several months and events are listed below according to the month they had happened.

The Cartel of the Suns is a Venezuelan organization supposedly headed by high-ranking members of the Armed Forces of Venezuela who are involved in international drug trade. According to Héctor Landaeta, journalist and author of Chavismo, Narco-trafficking and the Military, the phenomenon began when Colombian drugs began to enter into Venezuela from corrupt border units and the "rot moved its way up the ranks."

In 2014, a series of protests, political demonstrations, and civil insurrection began in Venezuela due to the country's high levels of urban violence, inflation, and chronic shortages of basic goods attributed to economic policies such as strict price controls. Mass protesting began in earnest in February following the attempted rape of a student on a university campus in San Cristóbal. Subsequent arrests and killings of student protesters spurred their expansion to neighboring cities and the involvement of opposition leaders. The year's early months were characterized by large demonstrations and violent clashes between protesters and government forces that resulted in nearly 4,000 arrests and 43 deaths, including both supporters and opponents of the government.

The 2017 Venezuelan protests began in late January following the abandonment of Vatican-backed dialogue between the Bolivarian government and the opposition. The series of protests originally began in February 2014 when hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protested due to high levels of criminal violence, inflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods because of policies created by the Venezuelan government though the size of protests had decreased since 2014. Following the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis, protests began to increase greatly throughout Venezuela.

The 2017 Venezuelan protests were a series of protests occurring throughout Venezuela. Protests began in January 2017 after the arrest of multiple opposition leaders and the cancellation of dialogue between the opposition and Nicolás Maduro's government.

On 27 June 2017, there was an incident involving a police helicopter at the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) and Interior Ministry in Caracas, Venezuela. Claiming to be a part of an anti-government coalition of military, police and civilians, the occupants of the helicopter allegedly launched several grenades and fired at the building, although no one was injured or killed. President Nicolás Maduro called the incident a "terrorist attack". The helicopter escaped and was found the next day in a rural area. On 15 January 2018, Óscar Pérez, the pilot and instigator of the incident, was killed during a military raid by the Venezuelan army that was met with accusations of extrajudicial killing.

2018 protests in Venezuela began in the first days of January as a result of high levels of hunger by desperate Venezuelans. Within the first two weeks of the year, hundreds of protests and looting incidents occurred throughout the country. By late-February, protests against the Venezuelan presidential elections occurred after several opposition leaders were banned from participating. Into March, the Maduro government began to crack down on military dissent, arresting dozens of high-ranking officials including former SEBIN director Miguel Rodríguez Torres.

Óscar Alberto Pérez was a Venezuelan rebel leader and an investigator for the CICPC, Venezuela's investigative agency. He was also an actor in a film to promote the role of detectives in the CICPC. He is better known for being responsible for the Caracas helicopter incident during the 2017 Venezuelan protests and the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis. His killing in the El Junquito raid received worldwide attention by the media and the political establishment, and was met with accusations of extrajudicial killing.

The El Junquito raid was a police and military raid that occurred on 15 January 2018 in El Junquito, Capital District, Venezuela, which resulted in the death of rebel Óscar Alberto Pérez and members of his movement.

The 2019 Venezuelan protests began in the first days of January as a result of the Venezuelan presidential crisis. Protests against the legitimacy of the Nicolás Maduro's presidency began at the time of his second inauguration following a controversial presidential election in 2018. Rallies of support were also held for President of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, with some Venezuelans and foreign government's recognizing him as the acting President of Venezuela.

The Russian–Venezuelan Threat Mitigation Act is a bill in the 116th United States Congress sponsored by Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) and co-sponsored by Mario Díaz-Balart (R-FL), Donna Shalala (D-FL), and Debbie Mucarsel-Powell (D-FL). It aims to monitor and investigate Russia's increasing involvement in the 2019 Venezuelan presidential crisis and the crisis in Venezuela in general.

Defections from the Bolivarian Revolution occurred under the administrations of Presidents Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro. The 2019 Venezuelan presidential crisis concerning who is the legitimate President of Venezuela has been underway since 10 January 2019, when the opposition-majority National Assembly declared that incumbent Nicolás Maduro's 2018 reelection was invalid and the body declared its president, Juan Guaidó, to be acting president of the nation. Guaidó encouraged military personnel and security officials to withdraw support from Maduro, and offered an amnesty law, approved by the National Assembly, for military personnel and authorities who help to restore constitutional order.

Bladimir Humberto Lugo Armas is a brigadier general of the Venezuelan National Guard. By 2017, he was the commander of the unit of this force that guarded the Federal Legislative Palace, the government buildings of Venezuela.