Related Research Articles

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Western Church. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental, Presbyterian, and Congregational traditions, as well as parts of the Anglican and Baptist traditions.

John Calvin was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism, including its doctrines of predestination and of God's absolute sovereignty in the salvation of the human soul from death and eternal damnation. Calvinist doctrines were influenced by and elaborated upon the Augustinian and other Christian traditions. Various Congregational, Reformed and Presbyterian churches, which look to Calvin as the chief expositor of their beliefs, have spread throughout the world.

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby God's omniscience seems incompatible with human free will. In this usage, predestination can be regarded as a form of religious determinism; and usually predeterminism, also known as theological determinism.

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism and in turn resulted in a major schism within Western Christianity.

The priesthood of all believers is either the general Christian belief that all Christians form a common priesthood, or, alternatively, the specific Protestant belief that this universal priesthood precludes the ministerial priesthood found in some other churches, including Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

In Western Christian theology, grace is created by God who gives it as help to one because God desires one to have it, not necessarily because of anything one has done to earn it. It is understood by Western Christians to be a spontaneous gift from God to people – "generous, free and totally unexpected and undeserved" – that takes the form of divine favor, love, clemency, and a share in the divine life of God. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, grace is the uncreated Energies of God. Among Eastern Christians generally, grace is considered to be the partaking of the Divine Nature described in 2 Peter 1:4 and grace is the working of God himself, not a created substance of any kind that can be treated like a commodity.

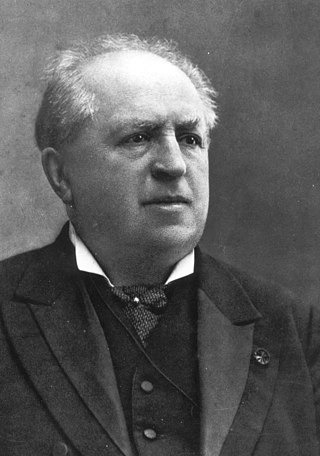

Abraham Kuyper was the Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1901 and 1905, an influential neo-Calvinist pastor and a journalist. He established the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, which upon its foundation became the second largest Reformed denomination in the country behind the state-supported Dutch Reformed Church.

Secularity, also the secular or secularness, is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself and fleshed out through Christian history into the modern era. In the medieval period there were even secular clergy. Furthermore, secular and religious entities were not separated in the medieval period, but coexisted and interacted naturally. The word "secular" has a meaning very similar to profane as used in a religious context.

In theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's intervention in the Universe. The term Divine Providence is also used as a title of God. A distinction is usually made between "general providence", which refers to God's continuous upholding of the existence and natural order of the Universe, and "special providence", which refers to God's extraordinary intervention in the life of people. Miracles and even retribution generally fall in the latter category.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is a book written by Max Weber, a German sociologist, economist, and politician. It began as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and '05, and was translated into English for the first time by American sociologist Talcott Parsons in 1930. It is considered a founding text in economic sociology and a milestone contribution to sociological thought in general.

Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. The term Protestant comes from the Protestation at Speyer in 1529, where the nobility protested against enforcement of the Edict of Worms which subjected advocates of Lutheranism to forfeit all of their property. However, the theological underpinnings go back much further, as Protestant theologians of the time cited both Church Fathers and the Apostles to justify their choices and formulations. The earliest origin of Protestantism is controversial; with some Protestants today claiming origin back to people in the early church deemed heretical such as Jovinian and Vigilantius.

The history of the Calvinist–Arminian debate begins in early 17th century in the Netherlands with a Christian theological dispute between the followers of John Calvin and Jacobus Arminius, and continues today among some Protestants, particularly evangelicals. The debate centers around soteriology, or the study of salvation, and includes disputes about total depravity, predestination, and atonement. While the debate was given its Calvinist–Arminian form in the 17th century, issues central to the debate have been discussed in Christianity in some form since Augustine of Hippo's disputes with the Pelagians in the 5th century.

Vocational discernment is the process by which men and women in the Catholic Church discern, or recognize, their vocation in the church and the world. The vocations are the life of a layperson in the world, either married or single, the ordained life of bishops, priests, and deacons, and consecrated religious life.

Reformed Christianity originated with the Reformation in Switzerland when Huldrych Zwingli began preaching what would become the first form of the Reformed doctrine in Zürich in 1519.

Protestant views on Mary include the theological positions of major Protestant representatives such as Martin Luther and John Calvin as well as some modern representatives. While it is difficult to generalize about the place of Mary, mother of Jesus in Protestantism given the great diversity of Protestant beliefs, some summary statements are attempted.

Lutheran Mariology or Lutheran Marian theology is derived from Martin Luther's views of Mary, the mother of Jesus and these positions have influenced those taught by the Lutheran Churches. Lutheran Mariology developed out of the deep Christian Marian devotion on which Luther was reared, and it was subsequently clarified as part of his mature Christocentric theology and piety. Lutherans hold Mary in high esteem, universally teaching the dogmas of the Theotokos and the Virgin Birth. Luther dogmatically asserted what he considered firmly established biblical doctrines such as the divine motherhood of Mary while adhering to pious opinions of the Immaculate Conception and the perpetual virginity of Mary, along with the caveat that all doctrine and piety should exalt and not diminish the person and work of Jesus Christ. By the end of Luther's theological development, his emphasis was always placed on Mary as merely a receiver of God's love and favour. His opposition to regarding Mary as a mediatrix of intercession or redemption was part of his greater and more extensive opposition to the belief that the merits of the saints could be added to those of Jesus Christ to save humanity. Lutheran denominations may differ in their teaching with respect to various Marian doctrines and have contributed to producing ecumenical meetings and documents on Mary.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes justification of sinners through faith alone, the teaching that salvation comes by unmerited divine grace, the priesthood of all believers, and the Bible as the sole infallible source of authority for Christian faith and practice. The five solae summarize the basic theological beliefs of mainstream Protestantism.

The Protestant Reformation began in 1520s in the Italian states, although forms of pre-Protestantism were already present before the 16th century. The Reformation in Italy collapsed quickly at the beginning of the 17th century. Its development was hindered by the Inquisition and also popular disdain.

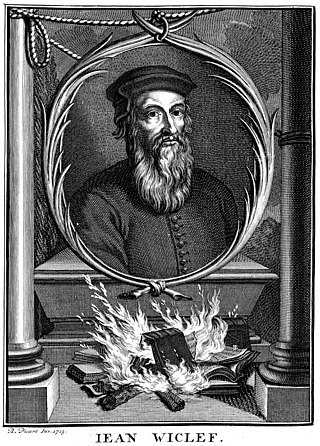

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated various ideas later associated with Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship between medieval sects and Protestantism is an issue that has been debated by historians.

References

- ↑ Richard A. Muller, Dictionary of Latin and Greek Theological Terms: Drawn Principally from Protestant Scholastic Theology (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House Company, 1985), s.v. "vocation."

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church: Christ's Faithful - Hierarchy, Laity, Consecrated Life". The Holy See.

- ↑ The OED records effectively identical uses of "call" in English back to c. 1300: OED, "Call", 6 "To nominate by a personal "call" or summons (to special service or office);esp. by Divine authority..."

- ↑ Pope John Paul II, Familiaris Consortio, 11.4

- ↑ Gustaf Wingren, Luther on Vocation

- ↑ David L. Jeffrey, A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0-8028-3634-8, ISBN 978-0-8028-3634-2, Google books See also Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism , trans. Alcott Parsons, Ch.3, p. 79 & note 1.

- 1 2 Calvin, John (1536). Institutes of the Christian Religion .

- ↑ Kenneth G. Appold. Abraham Calov's doctrine of vocatio in its systematic context, p. 125 and generally, Mohr Siebeck, 1998, ISBN 3-16-146858-9, ISBN 978-3-16-146858-2, Google books. See also Jeffrey, 815

- 1 2 Mather, Cotton (1701). A Christian at his Calling.

- ↑ Carlyle, Thomas (1843). Past and Present. Scribner, Welford.

- ↑ King James Version

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – part 3, section 2, chapter 2, article 6". The Holy See. Retrieved 2023-03-11.

- ↑ OED, "call", 6b

- ↑ "Calling". Glossary. LDS Church. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Ludlow, Daniel H. (1992). "Clergy". Encyclopedia of Mormonism . Brigham Young University . Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Oaks, Dallin H. (2002-11-01). "I'll Go Where You Want Me to Go". Liahona . LDS Church . Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- 1 2 Brian L. Pitcher, "Callings" in Encyclopedia of Mormonism .

- ↑ Douglas J. Schuurman; Vocation: Discerning Our Callings in Life (Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004) ISBN 978-0-8028-0137-1 pages 5, 6

- ↑ Ryken, L. (2002), Work and Leisure, 147.

- ↑ Pope Francis (2015), Laudato si', paragraph 129, accessed 28 January 2024