Washington Square is a park in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. It is located behind City Hall at the corner of Meeting Street and Broad Street in the Charleston Historic District. The planting beds and red brick walks were installed in April 1881. It was known as City Hall Park until October 19, 1881, when it was renamed in honor of George Washington. The new name was painted over the gates in December 1881.

Marion Square is greenspace in downtown Charleston, South Carolina, spanning ten acres. The square was established as a parade ground for the state arsenal under construction on the square's north side. It is best known as the former Citadel Green because The Citadel occupied the arsenal from 1843 until 1922 when the Citadel moved to the city's west side. Marion Square was named in honor of Francis Marion.

The Blake Tenements were built between 1760 and 1772 by Daniel Blake, a planter from Newington Plantation on the Ashley River. The building was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. The building was renovated for use as an annex to a nearby county office building in 1969.

The Gov. William Aiken House was built in 1820 at 48 Elizabeth Street, in the Wraggborough neighborhood of Charleston, South Carolina. Despite being known for its association with Gov. William Aiken, the house was built by John Robinson after he bought several lots in Mazyck-Wraggborough in 1817. His house was originally configured as a Charleston double house with entrance to the house from the south side along Judith Street. The house is considered to be the best preserved complex of antebellum domestic structures in Charleston. It was the home of William Aiken, Jr., a governor of South Carolina, and before that the home of his father, the owner of South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company, William Aiken.

Hampton Park Terrace is the name both of a neighborhood and a National Register district located in peninsular Charleston, South Carolina. The neighborhood is bounded on the west by The Citadel, on the north by Hampton Park, on the east by Rutledge Ave., and on the south by Congress St. In addition, the one block of Parkwood Ave. south of Congress St. is considered, by some, to be included. The National Register district, on the other hand, is composed of the same area with two exceptions: (1) the northeasternmost block is excluded and (2) an extra block of President St. is included.

Brittlebank Park is a ten-acre park located between Lockwood Boulevard and the Ashley River in Charleston, South Carolina near Gadsden Creek. To the south is a condominium project and to the north is the minor league baseball stadium, the Joseph P. Riley Jr. Park.

Corrine Jones Playground was formerly known as Hester Park because of its location along Hester Street in Charleston, South Carolina. The playground is located on a portion of the larger Buist Tract that had been used during World War II as housing for the influx of wartime workers.

The Patrick O'Donnell House is the largest example of Italianate architecture in Charleston, South Carolina. It was built for Patrick O'Donnell (1806-1882), perhaps in 1856 or 1857. Other research has suggested a construction date of 1865. Local lore has it that the three-and-a-half-story house was built for his would-be bride who later refused to marry him, giving rise to the house's popular name, "O'Donnell's Folly." Between 1907 and 1937, it was home to Josephine Pinckney; both the Charleston Poetry Society and the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals were formed at the house during her ownership.

The Carolina Rifles Armory at 158-160 King St., Charleston, South Carolina, was a late 19th-century headquarters for a semi-private military group, but today only the façade remains, facing an annex for the Charleston Library Society.

The Hannah Enston Building is a post-bellum commercial building at 171-173 King St., Charleston, South Carolina. A former building, constructed for furniture dealer William Enston, was burned in a fire in 1861. The replacement building was in place by 1872 when it was included in a bird's eye view map of Charleston. The building was built in the Gothic Revival style with similar decorative elements to 187-189-191 King St., a building built for William Enston sometime after 1848. After the death of William Enston, his property eventually was received by the trustees of a charity which he created to build the William Enston Home, and the trustees sold 171-173 King St. in 1888. From 1888 to 1909, the two halves of the building were separately owned. The southern portion of the building at 171 King St. was operated as a grocery by George Mazo; his son, writer Earl Mazo, and the rest of the family lived on the second floor.

The Gaillard Center is a concert hall and performance venue in Charleston, South Carolina. It opened in 2015 and replaced the Gaillard Municipal Auditorium. Both buildings were named after John Palmer Gaillard Jr., mayor of Charleston from 1959 to 1975.

The Faber House is a historic building in Hampstead Village in Charleston, South Carolina that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019.

Yeamans Hall Club is a country club built on a 1100-acre tract about 12 miles from Charleston, South Carolina, in the town of Hanahan, South Carolina. It is located along the Cooper River on the site of a 17th-century plantation.

Runnymede was a plantation home at 3760 Ashley River Road near Charleston, South Carolina. The land borders Magnolia Gardens to the southeast.

Memminger Auditorium is a live performance and special events venue in Charleston, South Carolina.

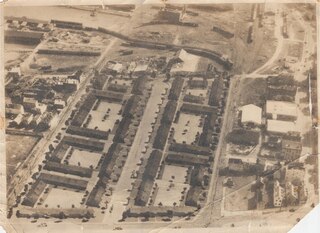

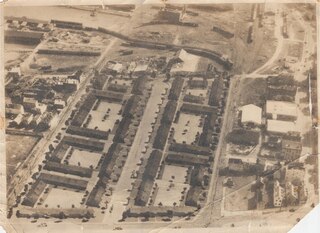

Meeting Street Manor is a housing complex located in the upper Eastside in Charleston, South Carolina, and was the city's first housing development. When built in the 1930s, the development was technically two racially segregated halves with separate names. Since desegregation, both components are typically referred to as Meeting Street Manor, originally the name for the Whites-only portion.

The Florence Crittenton Home is an institution for the support of unwed mothers at 19 St. Margaret St. in Charleston, South Carolina that is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Gadsden Green Homes is a housing complex located in the Westside neighborhood in Charleston, South Carolina. The name comes from the neighborhood which had been owned by Christopher Gadsden. The housing project was built in two stages: the eastern half was constructed in 1942 while the western half was finished in 1968.

Kiawah Homes is a housing complex located in the Wagener Terrace neighborhood in Charleston, South Carolina. It was built in 1942 as part of a federal housing program for World War II laborers and sold to the Charleston Housing Authority in 1954.

Anson Borough Homes was a housing complex located in Charleston, South Carolina bounded by Washington, Concord, Calhoun, and Laurens Streets. The project was one of a series of federally funded housing projects built in the 1930s and early 1940s during the Segregation Era. It meant to be used as housing for Black residents and would cost $2.30 per room per month.