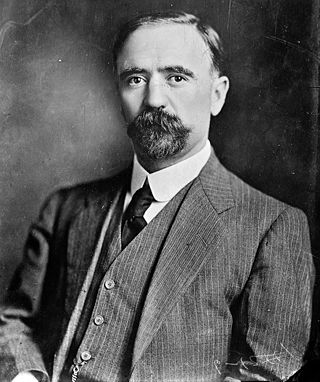

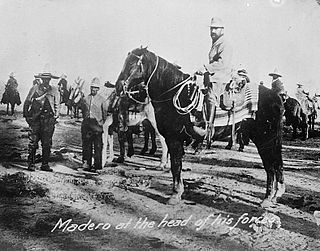

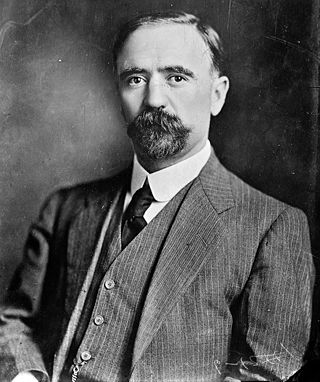

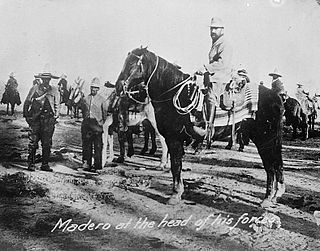

Francisco Ignacio Madero González was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who served as the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'état in February 1913 and assassinated. He came to prominence as an advocate for democracy and as an opponent of President and de facto dictator Porfirio Díaz. After Díaz claimed to have won the fraudulent election of 1910 despite promising a return to democracy, Madero started the Mexican Revolution to oust Díaz. The Mexican revolution would continue until 1920, well after Madero and Díaz's deaths, with hundreds of thousands dead.

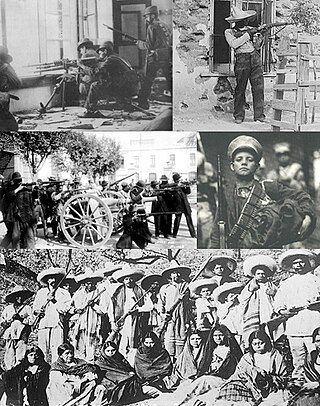

Francisco "Pancho" Villa was a Mexican revolutionary. A general in the Mexican Revolution, he was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced out President Porfirio Díaz and brought Francisco I. Madero to power in 1911. When Madero was ousted by a coup led by General Victoriano Huerta in February 1913, Villa joined the anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army led by Venustiano Carranza. After the defeat and exile of Huerta in July 1914, Villa broke with Carranza. Villa dominated the meeting of revolutionary generals that excluded Carranza and helped create a coalition government. Emiliano Zapata and Villa became formal allies in this period. Like Zapata, Villa was strongly in favor of land reform, but did not implement it when he had power. At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, the U.S. considered recognizing Villa as Mexico's legitimate authority.

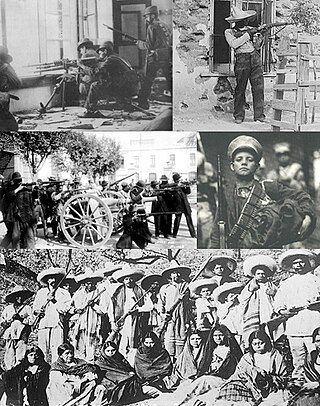

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history" and resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly noncombatants.

The Zimmermann telegram was a secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military contract between the German Empire and Mexico if the United States entered World War I against Germany. With Germany's aid, Mexico would recover Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. The telegram was intercepted by British intelligence.

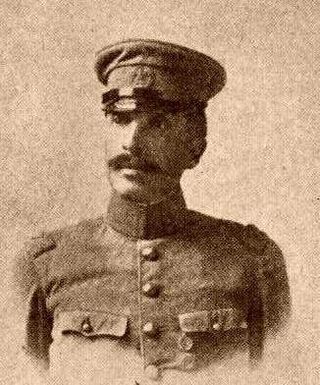

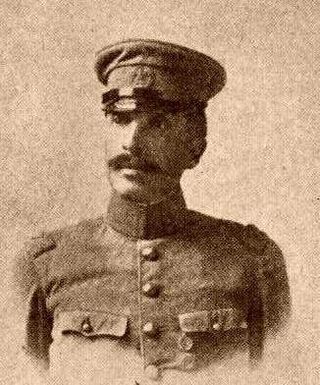

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero with the aid of other Mexican generals and the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. His violent seizure of power set off a new wave of armed conflict in the Mexican Revolution.

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Revolution. He was previously Mexico's de facto head of state as Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist faction from 1914 to 1917, and previously served as a senator and governor for Coahuila. He played the leading role in drafting the Constitution of 1917 and maintained Mexican neutrality in World War I.

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving United States Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detained by Mexican forces. Commanding Admiral Henry Mayo demanded that the US sailors be released, Mexico issue an apology, and raise and salute the US flag along with a 21 gun salute. Mexico refused the demand. US President Woodrow Wilson backed the admiral's demand. The conflict escalated when the Americans took the port city of Veracruz, occupying it for more than six months. This contributed to the fall of Huerta, who resigned in July 1914. Since the US did not have diplomatic relations with Mexico following Huerta's seizure of power in 1913, the ABC powers offered to mediate the conflict, in the Niagara Falls peace conference, held in Canada. The American occupation of Veracruz resulted in widespread anti-American sentiment.

The United States occupation of Veracruz began with the Battle of Veracruz and lasted for seven months. The incident came in the midst of poor diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States, and was related to the ongoing Mexican Revolution.

The Liberation Army of the South was a guerrilla force led for most of its existence by Emiliano Zapata that took part in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. During that time, the Zapatistas fought against the national governments of Porfirio Díaz, Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza. Their goal was rural land reform, specifically reclaiming communal lands stolen by hacendados in the period before the revolution. Although rarely active outside their base in Morelos, they allied with Pancho Villa to support the Conventionists against the Carrancistas. After Villa's defeat, the Zapatistas remained in open rebellion. It was only after Zapata's 1919 assassination and the overthrow of the Carranza government that Zapata's successor, Gildardo Magaña, negotiated peace with President Álvaro Obregón.

Félix Díaz Prieto was a Mexican politician and general born in Oaxaca, Oaxaca. He was a leading figure in the rebellion against President Francisco I. Madero during the Mexican Revolution. He was the nephew of president Porfirio Díaz.

Felipe Ángeles Ramírez (1868–1919) was a Mexican military officer and revolutionary during the era of the Mexican Revolution. Having risen to the rank of colonel of artillery in the Federal Army of the Porfiriato, Ángeles was promoted to general during the brief presidency of Francisco I. Madero. After the Ten Tragic Days, he became unique in the history of the revolution by becoming the only Federal general to join the revolutionary cause in northern Mexico, serving with General Pancho Villa's División del Norte.

In the history of Mexico, the Plan of Guadalupe was a political manifesto which was proclaimed on March 26, 1913, by the Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza in response to the reactionary coup d'etat and execution of President Francisco I. Madero, which had occurred during the Ten Tragic Days of February 1913. The manifesto was released from the Hacienda De Guadalupe, which is where the Plan derives its name, nearly a month after the assassination of Madero. The initial plan was limited in scope, denouncing Victoriano Huerta's usurpation of power and advocating the restoration of a constitutional government. In 1914, Carranza issued "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe", which broadened its scope and "endowed la Revolución with its social and economic content." In 1916, he further revised the Plan now that the Constitutionalist Army was victorious and revolutionaries sought changes to the 1857 Constitution of Mexico. Carranza sought to set the terms of the constitutional convention.

The United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution was varied and seemingly contradictory, first supporting and then repudiating Mexican regimes during the period 1910–1920. For both economic and political reasons, the U.S. government generally supported those who occupied the seats of power, but could withhold official recognition. The U.S. supported the regime of Porfirio Díaz after initially withholding recognition since he came to power by coup. In 1909, Díaz and U.S. President Taft met in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, Texas. Prior to Woodrow Wilson's inauguration on March 4, 1913, the U.S. Government focused on just warning the Mexican military that decisive action from the U.S. military would take place if lives and property of U.S. nationals living in the country were endangered. President William Howard Taft sent more troops to the US-Mexico border but did not allow them to intervene directly in the conflict, a move which Congress opposed. Twice during the Revolution, the U.S. sent troops into Mexico, to occupy Veracruz in 1914 and to northern Mexico in 1916 in a failed attempt to capture Pancho Villa. U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America was to assume the region was the sphere of influence of the U.S., articulated in the Monroe Doctrine. However the U.S. role in the Mexican Revolution has been exaggerated. It did not directly intervene in the Mexican Revolution in a sustained manner.

The Ten Tragic Days during the Mexican Revolution is the name given to the multi-day coup d'état in Mexico City by opponents of Francisco I. Madero, the democratically elected president of Mexico, between 9–19 February 1913. It instigated a second phase of the Mexican Revolution, after dictator Porfirio Díaz had been ousted and replaced in elections by Francisco I. Madero. The coup was carried out by general Victoriano Huerta and supporters of the old regime, with support from the United States.

Manuel Peláez Gorrochotegui (1885–1959) Mexican military officer, noteworthy for his participation in the Mexican Revolution of 1910 to 1920.

Paul von Hintze was a German naval officer, diplomat, and politician who served as Foreign Minister of Germany in the last stages of World War I, from July to October 1918.

Mexico was a neutral country in World War I, which lasted from 1914 to 1918. The war broke out in Europe in August 1914 as the Mexican Revolution was in the midst of full-scale civil war between factions that had helped oust General Victoriano Huerta from the presidency earlier that year. The Constitutionalist Army of Venustiano Carranza under the generalship of Alvaro Obregón defeated the army of Pancho Villa in the Battle of Celaya in April 1915.

The Mexican Border War, also known as the Border Campaign, refers to a series of military engagements which took place between the United States military and several Mexican factions in the Mexican–American border region of North America during the Mexican Revolution.

Felix A. Sommerfeld was a German secret service agent in Mexico and the United States between 1908 and 1919. He was chief of the Mexican secret service under President Francisco I. Madero, worked as a diplomat and arms buyer for Venustiano Carranza and Francisco "Pancho" Villa, and ran the Mexican portion of Germany's war strategy in North America between 1914 and 1917.