Related Research Articles

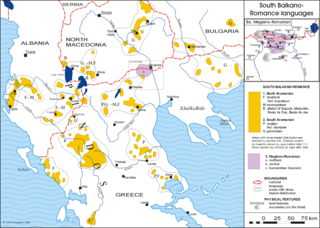

The Aromanians are an ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgaria, northern and central Greece and North Macedonia, and can currently be found in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgaria, south-western and eastern North Macedonia, northern and central Greece, southern Serbia and south-eastern Romania. An Aromanian diaspora living outside these places also exists. The Aromanians are known by several other names, such as "Vlachs" or "Macedo-Romanians".

Alcibiades Diamandi was an Aromanian political figure of Greece and Axis collaborator, active during the First and Second world wars in connection with the Italian occupation forces and Romania. By 1942, he fled to Romania and after the end of the Second World War he was sentenced by the Special Traitor's Courts in Greece to death. In Romania he was jailed by the new Communist government and died there in 1948.

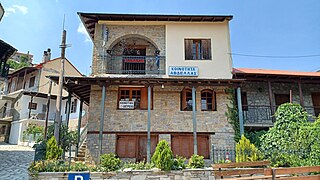

Avdella is a village and a former municipality in Grevena regional unit, Western Macedonia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been a municipal unit of Grevena. It is a seasonal Aromanian (Vlach) village. Located in the Pindus mountains at 1250–1350 metres altitude, its summer population is about 3000 and in the winter there are only a few residents. The 2021 census recorded 73 inhabitants. It is notable as the birthplace of the Manakis brothers, and appears in the opening sequence of the film Ulysses' Gaze. The community of Avdella covers an area of 43.243 km2.

Samarina is a village and a former municipality in Grevena regional unit, West Macedonia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Grevena, of which it is a municipal unit. Its population primarily consists of Aromanians (Vlachs). The population was 253 people as of 2021. It attracts many tourists due to its scenic location and beautiful pine and beech forests. The municipal unit has an area of 97.245 km2.

Nicolaos Matussis, also spelled as Nicolae Matussi, was an Aromanian lawyer, politician and leader of the Roman Legion, a collaborationist, separatist Aromanian paramilitary unit active during World War II in central Greece.

The Principality of the Pindus is a name given to describe a self-declared autonomous Aromanian political entity in the territory of Greece during World War II.

Nicolae Constantin Batzaria, was an Aromanian cultural activist, Ottoman statesman and Romanian writer. A schoolteacher and inspector of Aromanian education within Ottoman lands, he stood for the intellectual and political current, espoused by the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society, which closely identified with both Romanian nationalism and Ottomanism. Batzaria was trained at the University of Bucharest, where he became a disciple of historian Nicolae Iorga, and established his reputation as a journalist before 1908—the string of publications he founded, sometimes with financial support from the Kingdom of Romania, includes Românul de la Pind and Lumina. During his thirties, he joined the clandestine revolutionary movement known as the Young Turks, serving as its liaison with Aromanian factions in Macedonia and Rumelia. He was briefly imprisoned for such activities, but the victorious Young Turk Revolution in 1908 brought him to the forefront of Ottoman politics.

The Roman Legion, also known as the Vlach Legion in later bibliography, was a pro-Axis political and paramilitary organization active in Greece in 1941–1942, in the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia. It was created by Alcibiades Diamandi, an Aromanian (Vlach) from Samarina who served as an agent of Italy and Romania. The Roman Legion initially had around 2,000 members, and was supported by a small part of the local Aromanians. It consisted of the dregs of the local population, such as former criminals. It was dissolved in 1942.

Tache Papahagi was an Aromanian folklorist and linguist.

The Aromanians in Greece are an Aromanian ethno-linguistic group native in Epirus, Thessaly and Western and Central Macedonia, in Greece.

Zisis Vrakas was an important Greek chieftain of the Macedonian Struggle.

Vassilis Christou Rapotikas was an Aromanian brigand and collaborationist paramilitary leader in Greece during World War II. He was among leaders of the Roman Legion of the short-lived Italian puppet state of Pindus, right behind Alcibiades Diamandi and Nicolaos Matussis. This unit sought to carve out a permanent and independent Aromanian state in the Greek regions of Thessaly and Macedonia. Rapotikas was killed in May or June 1943 by members of the Greek People's Liberation Army near Grizano.

Aromanian nationalism is the ideology asserting the Aromanians as a distinct nation. A large number of Aromanians have moved away from nationalist themes such as the creation of a nation state of their own or achieving ethnic autonomy in the countries they live. Despite this, an ethnic-based identity and pride is prevalent in them. In history, Aromanian nationalists often found themselves divided into pro-Greek factions and pro-Romanian ones.

The Avdhela Project, also known as the Library of Aromanian Culture, is a digital library and cultural initiative developed by the Predania Association. The Avdhela Project aims to collect, edit and open to the public academic works on the Aromanians based on a series of specific principles. It was launched on 24 November 2009 in Bucharest, Romania. Public events, the promotion of cultural works and the publication of audiovisual material are other activities carried out by the Avdhela Project in support of Aromanian culture.

Samarina Republic or Republic of the Pindus is a historiographic name for the attempt and proposal to create an Aromanian canton under the protection of Italy during World War I. A declaration of independence was issued on 29 August 1917 by some Aromanian figures at Samarina and other villages of the Pindus mountains of northern Greece during the short period of occupation by Italy of the area in July and August 1917. In the immediate withdrawal of Italians a few days later, Greek troops retook control of the region claimed by the canton without meeting any resistance.

Stoica Lascu is a Romanian historian. He has authored over a dozen books and over 250 studies and articles in journals and volumes from Romania and abroad. An Aromanian from Dobruja, he specializes in the history of Romania, of his native region and of the Aromanians, as well as in various other topics.

Archimandrite Averchie or Averkios, born Atanasie Iaciu Buda, was an Aromanian monk and schoolteacher. Born in Avdella, he became hegumen and archimandrite in Mount Athos, where he was known as "Averchie the Vlach".

Aromanian literature is literature written in the Aromanian language. The first authors to write in Aromanian appeared during the second half of the 18th century in the metropolis of Moscopole, with a true cultured literature in Aromanian being born in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Notable authors include Constantin Belimace, author of the well-known anthem of the Aromanians Dimãndarea pãrinteascã ; Nuși Tulliu, whose novel Mirmintsã fãrã crutsi was the first in Aromanian; and Leon Boga, whose 150-sonnets epic poem Voshopolea ("Moscopole") founded the Aromanian literary trend of the utopian Moscopole. In theatre, Toma Enache has excelled.

George Ceara was an Aromanian poet, prose writer and schoolteacher. He was born in Xirolivado in the Ottoman Empire, now in Greece, and was raised in a transhumant lifestyle. After graduating from the Romanian High School of Bitola, he entered the University of Bucharest in Romania, though circumstances did not allow him to graduate.

References

Citations

- ↑ Chrysochoou 1951, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cândroveanu 1985, pp. 176–177.

- 1 2 3 4 Papahagi 1922, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cuvata 2001, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Lascu 2007, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 3 Carageani 1999, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chrysochoou 1951, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lascu 2007, pp. 151–152.

- 1 2 Chrysochoou 1951, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 Chrysochoou 1951, p. 53.

- ↑ Carageani 1999, p. 92.

- 1 2 Caragiu Marioțeanu 1968, pp. 439–440.

- ↑ Petcu 2016, p. 1956.

- ↑ Lascu 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ Lascu 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ Petcu 2016, p. 1915.

- ↑ Foti 1908, p. 31.

- ↑ Lascu 2007, p. 125.

- ↑ Lascu 2007, p. 150.

- ↑ Cândroveanu 1985, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 Lascu 2007, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Clogg 2021, pp. 85–87.

- ↑ Clogg 2021, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Lascu 2007, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Lascu 2007, pp. 156–158.

- 1 2 Clogg 2021, pp. 118–121.

- 1 2 Bozgan & Bozgan 1997, pp. 13–19.

- 1 2 Chrysochoou 1951, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Chrysochoou 1951, p. 22.

- 1 2 Chrysochoou 1951, p. 23.

- ↑ Chrysochoou 1951, p. 25.

- ↑ Chrysochoou 1951, pp. 45–48.

- ↑ Fonzi 2022, p. 129.

- 1 2 Chrysochoou 1951, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Clogg 2021, pp. 125–127.

Bibliography

- Bozgan, Evantia; Bozgan, Ovidiu (1997). "Aromânii și regimul național – legionar". Arhivele Totalitarismului (in Romanian). 5 (17): 8–22.

- Carageani, Gheorghe (1999). Studii aromâne (in Romanian). Editura Fundației Culturale Române. ISBN 9789735772239.

- Caragiu Marioțeanu, Matilda (1968). "Dialectul aromân" (PDF). In Iordan, Iorgu (ed.). Crestomație romanică (in Romanian). Vol. 3, part 1. Editura Academiei Române.

- Cândroveanu, Hristu (1985). Iorgoveanu, Kira (ed.). Un veac de poezie aromână (PDF) (in Romanian). Cartea Românească.

- Chrysochoou, Athanasios (1951). Η Κατοχή εν Μακεδονία. Βιβλίον τρίτον: η δράσις της ιταλορουμανικής προπαγάνδας (in Greek). Society for Macedonian Studies.

- Clogg, Richard (2021). A concise history of Greece (4 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108953924. ISBN 9781108953924.

- Cuvata, Dina (2001). Scriitori armãneshtsã (PDF) (in Aromanian). Union for Culture of the Aromanians of Macedonia.

- Fonzi, Paolo (2022). "Crossing intergroup borders. Forms of social brokerage in Italian occupied Greece (1941–43)" (PDF). Revista de Historia "Jerónimo Zurita". 100: 115–140.

- Foti, Ion (April 1908). "Cronica: o revistă franceză despre noi, un nou poet dialectal. O lămurire". Lumina (in Romanian). Vol. 6, no. 4. pp. 31–32.

- Lascu, Stoica (2007). "Evenimentele din lunile iulie-august 1917 în regiunea Munților Pind – încercare de creare a unei statalități a aromânilor. Documente inedite și mărturii. Studiu istoriografic și arhivistic". Revista Română de Studii Eurasiatice (in Romanian). 3 (1–2): 91–162.

- Lascu, Stoica (2013). "Elements of Romanian spirituality in the Balkans – Aromanian magazines and almanacs (1880–1914)". In Boldea, Iulian (ed.). Studies on literature, discourse and multicultural dialogue. Section Journalism. Editura Arhipelag XXI. pp. 15–36. ISBN 9786069359037.

- Papahagi, Tache (1922). Antologie aromănească (PDF) (in Romanian). Tipografia România Nouă.

- Petcu, Marian (2016). Istoria jurnalismului din România în date: enciclopedie cronologică (in Romanian). Elefant Online. ISBN 9789734638543.