Dianic Wicca, also known as Dianic Witchcraft, is a modern pagan, goddess tradition, focused on female experience and empowerment. Leadership is by women, who may be ordained as priestesses, or in less formal groups that function as collectives. While some adherents identify as Wiccan, it differs from most traditions of Wicca in that only goddesses are honored.

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Africa and the Near East. Although they share similarities, contemporary pagan movements are diverse, and do not share a single set of beliefs, practices, or texts. Scholars of religion may characterise these traditions as new religious movements. Some academics who study the phenomenon treat it as a movement that is divided into different religions while others characterize it as a single religion of which different pagan faiths are denominations. Because of these different approaches there is disagreement on when or if the term pagan should be capitalized, though specialists in the field of pagan studies tend towards capitalisation.

Wicca is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was introduced to the public in 1954 by Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant. Wicca draws upon a diverse set of ancient pagan and 20th-century hermetic motifs for its theological structure and ritual practices.

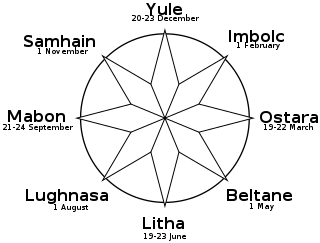

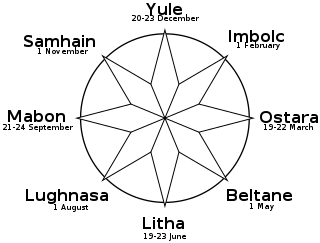

The Wheel of the Year is an annual cycle of seasonal festivals, observed by many modern pagans, consisting of the year's chief solar events and the midpoints between them. While names for each festival vary among diverse pagan traditions, syncretic treatments often refer to the four solar events as "quarter days", with the four midpoint events as "cross-quarter days". Differing sects of modern paganism also vary regarding the precise timing of each celebration, based on distinctions such as lunar phase and geographic hemisphere.

Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today is a sociological study of contemporary Paganism in the United States written by the American Wiccan and journalist Margot Adler. First published in 1979 by Viking Press, it was later republished in a revised and expanded edition by Beacon Press in 1986, with third and fourth revised editions being brought out by Penguin Books in 1996 and then 2006 respectively.

The History of Wicca documents the rise of the Neopagan religion of Wicca and related witchcraft-based Neopagan religions. Wicca originated in the early twentieth century, when it developed amongst secretive covens in England who were basing their religious beliefs and practices upon what they read of the historical Witch-Cult in the works of such writers as Margaret Murray. It also is based on the beliefs from the magic that Gerald Gardner saw when he was in Africa. It was subsequently Founded in the 1950's by Gardner, who claimed to have been initiated into the Craft – as Wicca is often known – by the New Forest coven in 1939. Gardner's form of Wicca, the Gardnerian tradition, was spread by both him and his followers like the High Priestesses Doreen Valiente, Patricia Crowther and Eleanor Bone into other parts of the British Isles, and also into other, predominantly English-speaking, countries across the world. In the 1960s, new figures arose in Britain who popularized their own forms of the religion, including Robert Cochrane, Sybil Leek and Alex Sanders, and organizations began to be formed to propagate it, such as the Witchcraft Research Association. It was during this decade that the faith was transported to the United States, where it was further adapted into new traditions such as Feri, 1734 and Dianic Wicca in the ensuing decades, and where organizations such as the Covenant of the Goddess were formed.

Neopagans are a religious minority in every country where they exist and have been subject to religious discrimination and/or religious persecution. The largest neopagan communities are in North America and the United Kingdom, and the issue of discrimination receives most attention in those locations, but there are also reports from Australia and Greece.

The Modern Pagan movement in the United Kingdom is primarily represented by Wicca and Witchcraft religions, Druidry, and Heathenry. 74,631 people in England, Scotland and Wales identified as either as Pagan or a member of a specific Modern Pagan group in the 2011 UK Census.

Since its emergence in the 1970s, Neopaganism in German-speaking Europe has diversified into a wide array of traditions, particularly during the New Age boom of the 1980s.

Italy, Spain, and Portugal are traditionally Roman Catholic and according to the 2005 Eurobarometer Poll retain an above-average belief in God. France is traditionally Roman Catholic as well and has an above-average fraction of atheists. Romania and Moldova are Eastern Orthodox countries and both are very religious.

Neopaganism in Hungary is very diverse, with followers of the Hungarian Native Faith and of other religions, including Wiccans, Kemetics, Mithraics, Druids and Christopagans.

Semitic neopaganism is a group of religions based on or attempting to reconstruct the ancient Semitic religions, mostly practiced among ethnic Jews in the United States.

Traditional witchcraft is a term used by certain esotericists who regard their practices as forms of witchcraft. The unifying feature of these religious movements is the attempt to differentiate themselves from the modern Pagan new religious movement of Wicca, whose followers typically call themselves witches, by emphasising "traditional" roots. Among traditions that have repeatedly been termed "traditional witchcraft" are Victor Henry Anderson's Feri Tradition, Robert Cochrane's Cochrane's Craft and Andrew D. Chumbley's Sabbatic Craft.

Minnesota's Twin Cities region is home to a large community of Wiccans, Witches, Druids, Heathens, and a number of Pagan organizations. Some neopagans in the USA refer to the area as Paganistan, a term coined by linguist, poet, and humorist Steven Posch in 1989, which he then used in the title of his spoken word album Radio Paganistan : Folktales of the Urban Witches.

A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-Paganism and Witchcraft in the United States is a sociological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the Northeastern United States. It was written by American sociologist Helen A. Berger of the West Chester University of Pennsylvania and first published in 1999 by the University of South Carolina Press. It was released as a part of a series of academic books entitled Studies in Comparative Religion, edited by Frederick M. Denny, a religious studies scholar at the University of Chicago.

Never Again the Burning Times: Paganism Revisited is an anthropological study of the Wiccan and wider Pagan community in the United States. It was written by the American anthropologist Loretta Orion and published by Waveland Press in 1995.

Living Witchcraft: A Contemporary American Coven is a sociological study of an American coven of Wiccans who operated in Atlanta, Georgia during the early 1990s. It was co-written by the sociologist Allen Scarboro, psychologist Nancy Campbell and literary critic Shirley Stave and first published by Praeger in 1994. Although largely sociological, the study was interdisciplinary, and included both insider and outsider perspectives into the coven; Stave was an initiate and a practicing Wiccan while Scarboro and Campbell remained non-initiates throughout the course of their research.

Modern paganviews on LGBT people vary considerably among different paths, sects, and belief systems. LGBT individuals comprise a much larger percentage of the population in neopagan circles than larger, mainstream religious populations. There are some popular neopagan traditions which have beliefs often in conflict with the LGBT community, and there are also traditions accepting of, created by, or led by LGBT individuals. The majority of conflicts concern heteronormativity and cisnormativity.