The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,300 kilometres (1,400 mi) over an area of approximately 344,400 square kilometres (133,000 sq mi). The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, Australia, separated from the coast by a channel 160 kilometres (100 mi) wide in places and over 61 metres (200 ft) deep. The Great Barrier Reef can be seen from outer space and is the world's biggest single structure made by living organisms. This reef structure is composed of and built by billions of tiny organisms, known as coral polyps. It supports a wide diversity of life and was selected as a World Heritage Site in 1981. CNN labelled it one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World in 1997. Australian World Heritage places included it in its list in 2007. The Queensland National Trust named it a state icon of Queensland in 2006.

Spearfishing is fishing using handheld elongated, sharp-pointed tools such as a spear, gig, or harpoon, to impaling the fish in the body. It was one of the earliest fishing techniques used by mankind, and has been deployed in artisanal fishing throughout the world for millennia. Early civilizations were familiar with the custom of spearing fish from rivers and streams using sharpened sticks.

The Neptune Islands consist of two groups of islands located close to the entrance to Spencer Gulf in South Australia. They are well known as a venue for great white shark tourism.

Rodney Winston Fox is an Australian film maker, conservationist, survivor of an attack by a great white shark, and one of the world's foremost authorities on that species. He was inducted into the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame in 2007. He was born in Adelaide.

The 1992 cageless shark-diving expedition was the world's first recorded intentionally cageless dive with great white sharks, contributing to a change in public opinions about the supposed ferocity of these animals.

The Ningaloo Coast is a World Heritage Site located in the north west coastal region of Western Australia. The 705,015-hectare (1,742,130-acre) heritage-listed area is located approximately 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) north of Perth, along the East Indian Ocean. The distinctive Ningaloo Reef that fringes the Ningaloo Coast is 260 kilometres (160 mi) long and is Australia's largest fringing coral reef and the only large reef positioned very close to a landmass. The Muiron Islands and Cape Farquhar are within this coastal zone.

Ron Josiah Taylor, AM was a prominent Australian shark expert, as is his widow, Valerie Taylor. They were credited with being pioneers in several areas, including being the first people to film great white sharks without the protection of a cage. Their expertise has been called upon for films such as Jaws, Orca and Sky Pirates.

Benjamin Cropp AM is an Australian documentary filmmaker, conservationist and a former six-time Open Australian spearfishing champion. Formerly a shark hunter, Cropp retired from that trade in 1962 to pursue oceanic documentary filmmaking and conservation efforts. One of his efforts for The Disney Channel, The Young Adventurers, was nominated for an Emmy award.

The International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame (ISDHF) is an annual event that recognizes those who have contributed to the success and growth of recreational scuba diving in dive travel, entertainment, art, equipment design and development, education, exploration and adventure. It was founded in 2000 by the Cayman Islands Ministry of Tourism. Currently, it exists virtually with plans for a physical facility to be built at a future time.

Shark tourism is a form of eco-tourism that allows people to dive with sharks in their natural environment. This benefits local shark populations by educating tourists and through funds raised by the shark tourism industry. Communities that previously relied on shark finning to make their livelihoods are able to make a larger profit from diving tours while protecting the local environment. People can get close to the sharks by free- or scuba diving or by entering the water in a protective cage for more aggressive species. Many of these dives are done by private companies and are often baited to ensure shark sightings, a practice which is highly controversial and under review in many areas.

The Australian Wildlife Society was established in Sydney, Australia in May 1909 as the Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia (WPSA) to encourage the protection of, and cultivate an interest in, Australia's flora and fauna. The founding president of the Society was The Hon. Frederick Earle Winchcombe MLC. David Stead was one of four vice presidents and a very active founder of the Society.

Cod Hole is one of the best known dive sites in the world and is located on the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia on ribbon reef number 10. It is notable for and is named after the dozen or so potato cod that live there. The sanctioned feeding of these fish and number of visitors to the site has also made it a focal point in the debate over reef management.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to sharks:

Jason deCaires Taylor is a British sculptor and creator of the world's first underwater sculpture park – the Molinere Underwater Sculpture Park – and underwater museum – Cancún Underwater Museum (MUSA). He is best known for installing site-specific underwater sculptures that develop naturally into artificial coral reefs, which local communities and marine life depend on. Taylor integrates his skills as a sculptor, marine conservationist, underwater photographer and scuba diving instructor into each of his projects. By using a fusion of Land Art traditions and subtly integrating aspects of street art, Taylor produces dynamic sculptural works that are installed on the ocean floor to encourage marine life, to promote ocean conservation and to highlight the current climate crisis.

The Australian Underwater Federation (AUF) is the governing body for underwater sports in Australia.

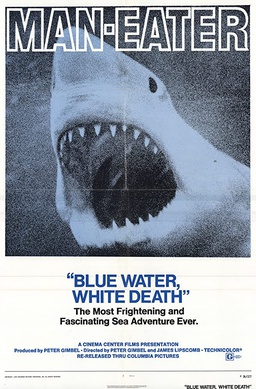

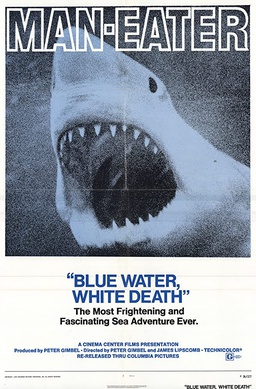

Blue Water, White Death is a 1971 American documentary film about sharks, which was directed by Peter Gimbel and James Lipscomb. It received favourable reviews and was described as a "well produced odyssey" and "exciting and often beautiful". It screened theatrically and was broadcast on television at various times during the 1970s and 1980s. The film was re-released on DVD in 2009.

Neptune Islands Conservation Park is a protected area occupying most of the Neptune Islands in South Australia about 55 km (34 mi) south-south east of Port Lincoln. It was established in 1967 principally to protect a New Zealand fur seal breeding colony. The conservation park was subsequently expanded to include the adjoining waters in order to control and manage berleying activities used to attract great white sharks. As of 2002, the conservation park is the only place in Australia where shark cage diving to view great white sharks is legally permitted.

Richard John Fitzpatrick is an Australian Emmy award winning cinematographer and adjunct research fellow specialising in marine biology at James Cook University.

The Ningaloo Marine Park is an Australian marine park offshore of Western Australia, and west of the Ningaloo Coast. The marine park covers an area of 2,435 km2 (940 sq mi) and is assigned IUCN category IV. It is one of the 13 parks managed under the North-west Marine Parks Network.

The Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA) is a series of underwater art installations near Townsville, Australia. The museum aims to promote the conservation of the Great Barrier Reef while acting as a public snorkelling and scuba diving attraction. It is the only underwater art museum in the Southern Hemisphere and consists of three sculptures created by British sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor. The museum opened in 2020.