Proposition 215, or the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, is a California law permitting the use of medical cannabis despite marijuana's lack of the normal Food and Drug Administration testing for safety and efficacy. It was enacted, on November 5, 1996, by means of the initiative process, and passed with 5,382,915 (55.6%) votes in favor and 4,301,960 (44.4%) against.

The Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) is the largest organization working solely on marijuana policy reform in the United States in terms of its budget, number of members, and staff.

Cannabis in Oregon is legal for both medical and recreational use. In recent decades, the U.S. state of Oregon has had a number of legislative, legal and cultural events surrounding the use of cannabis. Oregon was the first state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of cannabis and authorize its use for medical purposes. An attempt to recriminalize the possession of small amounts of cannabis was turned down by Oregon voters in 1997.

Initiative 1068 was a proposed initiative for the November 2010 Washington state general election that would have removed criminal penalties from the adult use, possession, and cultivation of marijuana in Washington. Sponsored by Vivian McPeak, Douglass Hiatt, Jeffrey Steinborn, Philip Dawdy, initiative I-1068 sought to legalize marijuana by removing marijuana offenses from the state's controlled substances act, but failed to gather enough signatures to qualify for the ballot.

Oregon Ballot Measure 80, also known as the Oregon Cannabis Tax Act, OCTA and Initiative-9, was an initiated state statute ballot measure on the November 6, 2012 general election ballot in Oregon. It would have allowed personal marijuana and hemp cultivation or use without a license and created a commission to regulate the sale of commercial marijuana. The act would also have set aside two percent of profits from cannabis sales to promote industrial hemp, biodiesel, fiber, protein, and oil.

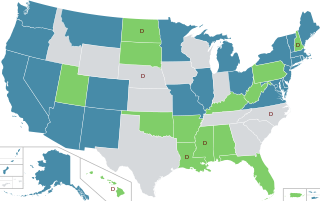

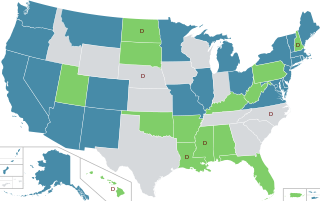

In the United States, cannabis is legal in 39 of 50 states for medical use and 24 states for recreational use. At the federal level, cannabis is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act, determined to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use, prohibiting its use for any purpose. Despite this prohibition, federal law is generally not enforced against the possession, cultivation, or intrastate distribution of cannabis in states where such activity has been legalized. Beginning in 2024, the Drug Enforcement Administration has initiated a review to potentially move cannabis to the less-restrictive Schedule III.

Cannabis in Massachusetts is legal for medical and recreational use. It also relates to the legal and cultural events surrounding the use of cannabis. A century after becoming the first U.S. state to criminalize recreational cannabis, Massachusetts voters elected to legalize it in 2016.

Cannabis is strictly illegal in Wyoming. The state has some of the strictest cannabis laws in the United States. Cannabis itself is not allowed for medical purposes, but a 2015 law allows limited use of non-psychoactive Cannabidiol. An effort was made to place two initiatives on the 2022 ballot, one to legalize medical cannabis, and the other to decriminalize personal use.

Cannabis in Montana has been legal for both medical and recreational use since January 1, 2021, when Initiative 190 went into effect. Prior to the November 2020 initiative, marijuana was illegal for recreational use starting in 1929. Medical cannabis was legalized by ballot initiative in 2004. The Montana Legislature passed a repeal to tighten Montana Medical Marijuana (MMJ) laws which were never approved by the governor. However, with the new provisions, providers could not service more than three patients. In November 2016 Bill I-182 was passed, revising the 2004 law and allowing providers to service more than three patients. In May 2023, numerous further bills on cannabis legalization and other related purposes passed the Montana Legislature. The Governor of Montana is yet to either sign or veto the bill.

Cannabis in Arkansas is illegal for recreational use. First-time possession of up to four ounces (110 g) is punished with a fine of up to $2,500, imprisonment of up to a year, and a mandatory six month driver's license suspension. Medical use was legalized in 2016 by way of a ballot measure to amend the state constitution.

Cannabis in North Dakota is legal for medical use but illegal for recreational use. Since 2019 however, possession under a 1/2 ounce has been decriminalized in the sense that there is no threat of jail time, though a criminal infraction fine up to $1,000 still applies. The cultivation of hemp is currently legal in North Dakota. In November 2018, the state's voters voted on recreational marijuana legalization, along with Michigan; the measure was rejected 59% to 41%. Two groups attempted to put marijuana legalization measures on the June 2020 Primary and the November 2020 elections, but were prevented from doing so by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cannabis in Oklahoma is illegal for recreational use, but legal for medical use with a state-issued license, while CBD oil derived from industrial hemp is legal without a license.

Cannabis in Nevada became legal for recreational use on January 1, 2017, following the passage of Question 2 on the 2016 ballot with 54% of the vote. The first licensed sales of recreational cannabis began on July 1, 2017.

The Florida Medical Marijuana Legalization Initiative, also known as Amendment 2, was approved by voters in the Tuesday, November 8, 2016, general election in the State of Florida. The bill required a super-majority vote to pass, with at least 60% of voters voting for support of a state constitutional amendment. Florida already had a medical marijuana law in place, but only for those who are terminally ill and with less than a year left to live. The goal of Amendment 2 is to alleviate those suffering from these medical conditions: cancer, epilepsy, glaucoma, positive status for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Crohn's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic nonmalignant pain caused by a qualifying medical condition or that originates from a qualified medical condition or other debilitating medical conditions comparable to those listed. Under Amendment 2, the medical marijuana will be given to the patient if the physician believes that the medical use of marijuana would likely outweigh the potential health risks for a patient. Smoking the medication was not allowed under a statute passed by the Florida State Legislature, however this ban was struck down by Leon County Circuit Court Judge Karen Gievers on May 25, 2018.

Cannabis in Arizona is legal for recreational use. A 2020 initiative to legalize recreational use passed with 60% of the vote. Possession and cultivation of recreational cannabis became legal on November 30, 2020, with the first state-licensed sales occurring on January 22, 2021.

Cannabis in Missouri is legal for recreational use. A ballot initiative to legalize recreational use, Amendment 3, passed by a 53–47 margin on November 8, 2022. Possession for adults 21 and over became legal on December 8, 2022, with the first licensed sales occurring on February 3, 2023.

Cannabis in Maryland is legal for medical use and recreational use. Possession of up to 1.5 ounces and cultivation of up to 2 plants is legal for adults 21 years of age and older. In 2013, a state law was enacted to establish a state-regulated medical cannabis program. The program, known as the Natalie M. LaPrade Maryland Medical Cannabis Commission (MMCC) became operational on December 1, 2017.

Cannabis in Ohio is legal for recreational use. Issue 2, a ballot measure to legalize recreational use, passed by a 57–43 margin on November 7, 2023. Possession and personal cultivation of cannabis became legal on December 7, 2023. The first licensed sales started on August 6, 2024. Prior to legalization, Ohio decriminalized possession of up 100 grams in 1975, with several of the state's major cities later enacting further reforms.

Cannabis in Washington relates to a number of legislative, legal, and cultural events surrounding the use of cannabis. On December 6, 2012, Washington became the first U.S. state to legalize recreational use of marijuana and the first to allow recreational marijuana sales, alongside Colorado. The state had previously legalized medical marijuana in 1998. Under state law, cannabis is legal for medical purposes and for any purpose by adults over 21.

Cannabis in Michigan is legal for recreational use. A 2018 initiative to legalize recreational use passed with 56% of the vote. State-licensed sales of recreational cannabis began in December 2019.