Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea lasting a few days. Vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur. Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. This may result in sunken eyes, cold skin, decreased skin elasticity, and wrinkling of the hands and feet. Dehydration can cause the skin to turn bluish. Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure.

Maureen Mwanawasa was a Zambian legal practitioner who was first lady from 2002 to 2008. She was also a member of the Association of Women Lawyers in the United Kingdom, a serving council member of Law Association of Zambia Women’s Rights Committee, and the vice chairperson for the Habitat for Humanity, Zambia Board. She was the patron of Breakthrough Cancer Trust and the Child Care & Adoption Society of Zambia.

The 2008 Zimbabwean cholera outbreak was an epidemic of cholera affecting much of Zimbabwe from August 2008 until June 2009. The outbreak began in Chitungwiza in Harare Metropolitan Province in August 2008, then spread throughout the country so that by December 2008, cases were being reported in all 10 provinces. In December 2008, The Zimbabwean government declared the outbreak a national emergency and requested international aid. The outbreak peaked in January 2009 with 8,500 cases reported per week. Cholera cases from this outbreak were also reported in neighboring countries South Africa, Malawi, Botswana, Mozambique, and Zambia. With the help of international agencies, the outbreak was controlled, and by July 2009, after no cases had been reported for several weeks, the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare declared the outbreak over. In total, 98,596 cases of cholera and 4,369 deaths were reported, making this the largest outbreak of cholera ever recorded in Zimbabwe. The large scale and severity of the outbreak has been attributed to poor sanitation, limited access to healthcare, and insufficient healthcare infrastructure throughout Zimbabwe.

Yellow fever vaccine is a vaccine that protects against yellow fever. Yellow fever is a viral infection that occurs in Africa and South America. Most people begin to develop immunity within ten days of vaccination and 99% are protected within one month, and this appears to be lifelong. The vaccine can be used to control outbreaks of disease. It is given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

As of 24 September 2012, a cholera outbreak in Sierra Leone had caused the deaths of 392 people. It was the country's largest outbreak of cholera since first reported in 1970 and the deadliest since the 1994–1995 cholera outbreak. The outbreak has also affected Guinea, which shares a reservoir near the coast. This was the largest cholera outbreak in Africa in 2012.

An outbreak of cholera began in Yemen in October 2016. The outbreak peaked in 2017 with over 2,000 reported deaths in that year alone. In 2017 and 2019, war-torn Yemen accounted for 84% and 93% of all cholera cases in the world, with children constituting the majority of reported cases. As of November 2021, there have been more than 2.5 million cases reported, and more than 4,000 people have died in the Yemen cholera outbreak, which the United Nations deemed the worst humanitarian crisis in the world at that time. However, the outbreak has substantially decreased by 2021, with a successful vaccination program implemented and only 5,676 suspected cases with two deaths reported between January 1 and March 6 of 2021.

Sylvia Masebo is a Zambian entrepreneur, politician, and National Assembly of Zambia representative for Chongwe constituency with the United Party for National Development (UPND). Sylvia Masebo holds a degree in Banking and Finance. She first stood on the ticket of Zambian Republican Party (ZRP) in 2001, then the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) in 2003, then the Patriotic Front (PF) in 2011, and then the UPND in 2021.

The 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak occurred in the north-west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from May to July 2018. It was contained entirely within Équateur province, and was the first time that vaccination with the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak, with a total of 3,481 people vaccinated. It was the ninth recorded Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

The 2019 Samoa measles outbreak began in September 2019. As of 6 January 2020, there were over 5,700 cases of measles and 83 deaths, out of a Samoan population of 200,874. Over three per cent of the population were infected. The cause of the outbreak was attributed to decreased vaccination rates, from 74% in 2017 to 31–34% in 2018, even though nearby islands had rates near 99%.

The 2019 Tonga measles outbreak began in October 2019 after a squad of Tongan rugby players came back from New Zealand. As of 5 January, 2020, there have been 612 cases of measles.

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have spread to Africa on 14 February 2020, with the first confirmed case announced in Egypt. The first confirmed case in sub-Saharan Africa was announced in Nigeria at the end of February 2020. Within three months, the virus had spread throughout the continent, as Lesotho, the last African sovereign state to have remained free of the virus, reported a case on 13 May 2020. By 26 May, it appeared that most African countries were experiencing community transmission, although testing capacity was limited. Most of the identified imported cases arrived from Europe and the United States rather than from China where the virus originated.

The first confirmed case of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. state of Connecticut was confirmed on March 8, although there had previously been multiple people suspected of having COVID-19, all of which eventually tested negative. As of January 19, 2022, there were 599,028 confirmed cases, 68,202 suspected cases, and 9,683 COVID-associated deaths in the state.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Guinea-Bissau is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus was confirmed to have reached Guinea-Bissau in March 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Zambia was a part of the ongoing worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus was confirmed to have reached Zambia in March 2020.

The first confirmed case relating to the COVID-19 pandemic in Yemen was announced on 10 April 2020 with an occurrence in Hadhramaut. Organizations called the news a "devastating blow" and a "nightmare scenario" given the country's already dire humanitarian situation.

On 5 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) notified the world about "pneumonia of unknown cause" in China and subsequently followed up with investigating the disease. On 20 January, the WHO confirmed human-to-human transmission of the disease. On 30 January, the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and warned all countries to prepare. On 11 March, the WHO said that the outbreak constituted a pandemic. By 5 October the same year, the WHO estimated that a tenth of the world's population had been infected with the novel virus.

The following is a timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana during 2021-2022.

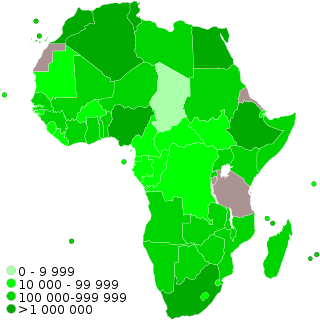

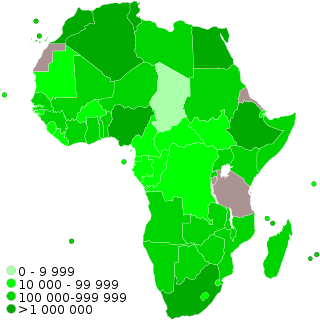

COVID-19 vaccination programs are ongoing in the majority countries and territories in Africa, with 51 of 54 African countries having launched vaccination programs by July 2021. As of October 2023, 51.8% of the continent's population is fully vaccinated with over 1084.5 million doses administered.

The 2022–2024 Southern Africa cholera outbreak is an outbreak that has spread across Southern Africa. It started in Machinga District in Malawi in March 2022. The cholera outbreak in Malawi linked to cases in South Africa, the strains belong to the seventh cholera pandemic. Rather than being a resurgence of a previously circulating strain in Africa, these cases likely resulted from the introduction of a new cholera agent from South Asia into Africa.

Events in the year 2024 in Zambia.