Aachen Cathedral is a Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the seat of the Diocese of Aachen.

The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram is a 9th-century illuminated Gospel Book. It takes its name from Saint Emmeram's Abbey, where it was for most of its history and is lavishly illuminated. The cover of the codex is decorated with gems and relief figures in gold, and can be precisely dated to 870, and is an important example of Carolingian art, as well as one of very few surviving treasure bindings of this date.

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

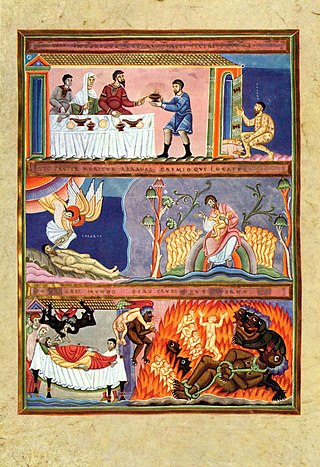

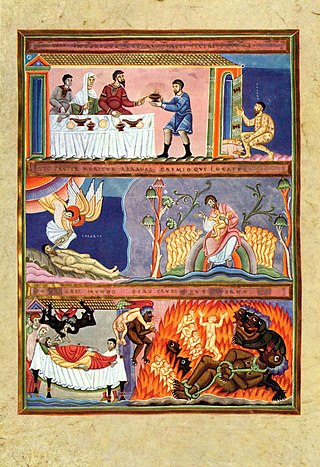

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and Northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II. With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance. However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own. In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

The Vienna Coronation Gospels, also known simply as the Coronation Gospels, is a late 8th century illuminated gospel book produced at the court of Charlemagne in Aachen. It was used by the future emperor at his coronation on Christmas Day 800, when he placed three fingers of his right hand on the first page of the Gospel of Saint John and took his oath. Traditionally, it is considered to be the same manuscript that was found in the tomb of Charlemagne when it was opened in the year 1000 by Emperor Otto III. The Coronation Evangeliar cover was created by Hans von Reutlingen, c. 1500. The Coronation Evangeliar is part of the Imperial Treasury (Schatzkammer) in the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria.

The Codex Aureus of Echternach is an illuminated Gospel Book, created in the approximate period 1030–1050, with a re-used front cover from around the 980s. It is now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.

The Cross of Lothair or Lothair Cross is a crux gemmata processional cross dating from about 1000 AD, though its base dates from the 14th century. It was made in Germany, probably at Cologne. It is an outstanding example of medieval goldsmith's work, and "an important monument of imperial ideology", forming part of the Aachen Cathedral Treasury, which includes several other masterpieces of sacral Ottonian art. The measurements of the original portion are 50 cm height, 38.5 cm width, 2.3 cm depth.

The Marienschrein in Aachen Cathedral is a reliquary, donated on the order of the chapter of Mary around 1220 and consecrated in 1239. Along with the Karlsschrein, the artwork, which is from the transitional period between romanesque and gothic, is among the most important goldsmith works of the thirteenth century.

The Noli me tangere casket was a small silver-gilt casket made in 1356 for the Aachen Cathedral Treasury. It measured 15.2 cm in length, 3.7 cm in height and 4.8 cm in width. The casket was kept in the Marienschrein together with the key relics of the cathedral until the nineteenth century and the casket remained in the possession of the cathedral treasury until its destruction during the Second World War.

The Bust of Charlemagne is a reliquary from around 1350 which contains the top part of Charlemagne's skull. The reliquary is part of the treasure kept in the Aachen Cathedral Treasury. Made in the Mosan region, long a centre of high-quality metalwork, the bust is a masterpiece both of late Gothic metalwork and of figural sculpture.

The Aachen Altar or Passion Altar (Passionsaltar) is a late gothic passion triptych in the Aachen Cathedral Treasury, made by the so-called Master of the Aachen Altar around 1515/20 in Cologne.

The Liuthar Gospels are a work of Ottonian illumination which are counted among the masterpieces of the period known as the Ottonian Renaissance. The manuscript, named after a monk called Liuthar, was probably created around the year 1000 at the order of Otto III at the Abbey of Reichenau and lends its name to the Liuthar Group of Reichenau illuminated manuscripts. The backgrounds of all the images are illuminated in gold leaf, a seminal innovation in western illumination.

The Aachen Cathedral Treasury is a museum of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen under the control of the cathedral chapter, which houses one of the most important collections of medieval church artworks in Europe. In 1978, the Aachen Cathedral Treasury, along with Aachen Cathedral, was the first monument on German soil to be entered in the List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The treasury contains works from Late Antique, Carolingian, Ottonian, Staufen, and Gothic times. The exhibits are displayed in premises connected to the cathedral cloisters.

The Essen Cathedral Treasury is one of the most significant collections of religious artworks in Germany. A great number of items of treasure are accessible to the public in the treasury chamber of Essen Minster. The cathedral chapter manages the treasury chamber, not as a museum as in some places, but as the place in which liturgical implements and objects are kept, which continued to be used to this day in the service of God, so far as their conservation requirements allow.

The notname Master of the Aachen Altar is given to an anonymous late gothic painter active in Cologne between 1495 and 1520 or 1480 and 1520, named for his master work, the Aachen Altar triptych owned by the Aachen Cathedral Treasury. Along with the Master of St Severin and the Master of the legend of St. Ursula he is part of a group of painters who were active in Cologne at the beginning of the sixteenth century and were Cologne's last significant practitioners of late gothic painting.

The Cross of Mathilde is an Ottonian processional cross in the crux gemmata style which has been in Essen in Germany since it was made in the 11th century. It is named after Abbess Mathilde who is depicted as the donor on a cloisonné enamel plaque on the cross's stem. It was made between about 1000, when Mathilde was abbess, and 1058, when Abbess Theophanu died; both were princesses of the Ottonian dynasty. It may have been completed in stages, and the corpus, the body of the crucified Christ, may be a still later replacement. The cross, which is also called the "second cross of Mathilde", forms part of a group along with the Cross of Otto and Mathilde or "first cross of Mathilde" from late in the preceding century, a third cross, sometimes called the Senkschmelz Cross, and the Cross of Theophanu from her period as abbess. All were made for Essen Abbey, now Essen Cathedral, and are kept in Essen Cathedral Treasury, where this cross is inventory number 4.

The Ambon of Henry II, commonly known as Henry's Ambon (Heinrichsambo) or Henry's Pulpit (Heinrichskanzel) is an ambon in the shape of a pulpit built by Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor in the Palatine chapel in Aachen between 1002 and 1014. It is among the most significant artworks of the Ottonian period.

The Essen Crown is an Ottonian golden crown in the Essen Cathedral Treasury. It was formerly claimed that it might have been the crown with which the three-year-old Otto III was crowned King of the Romans in 983, which is the source of its common name, the Childhood Crown of Otto III. However, this idea most probably derives from the wishful thinking of early twentieth century historians of Essen and it is now widely rejected. However it is certainly the oldest surviving lily crown in the world.

The Talisman of Charlemagne is a 9th-century Carolingian reliquary encolpion that may once have belonged to Charlemagne and is purported to contain a fragment of the True Cross. It is the only surviving piece of goldwork which can be connected with Charlemagne himself with some degree of probability, but the connection has been seriously questioned. The talisman is now kept in Rheims in the Palace of Tau.