An adiabatic process is a type of thermodynamic process that occurs without transferring heat between the thermodynamic system and its environment. Unlike an isothermal process, an adiabatic process transfers energy to the surroundings only as work and/or mass flow. As a key concept in thermodynamics, the adiabatic process supports the theory that explains the first law of thermodynamics. The opposite term to "adiabatic" is diabatic.

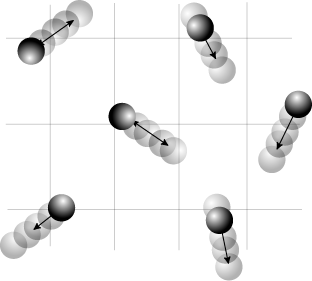

Entropy is a scientific concept that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the microscopic description of nature in statistical physics, and to the principles of information theory. It has found far-ranging applications in chemistry and physics, in biological systems and their relation to life, in cosmology, economics, sociology, weather science, climate change and information systems including the transmission of information in telecommunication.

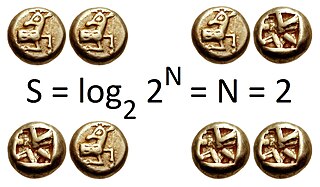

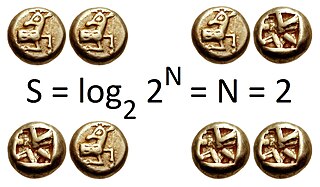

In information theory, the entropy of a random variable quantifies the average level of uncertainty or information associated with the variable's potential states or possible outcomes. This measures the expected amount of information needed to describe the state of the variable, considering the distribution of probabilities across all potential states. Given a discrete random variable , which takes values in the set and is distributed according to , the entropy is where denotes the sum over the variable's possible values. The choice of base for , the logarithm, varies for different applications. Base 2 gives the unit of bits, while base e gives "natural units" nat, and base 10 gives units of "dits", "bans", or "hartleys". An equivalent definition of entropy is the expected value of the self-information of a variable.

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal empirical observation concerning heat and energy interconversions. A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spontaneously from hotter to colder regions of matter. Another statement is: "Not all heat can be converted into work in a cyclic process."

The first law of thermodynamics is a formulation of the law of conservation of energy in the context of thermodynamic processes. The law distinguishes two principal forms of energy transfer, heat and thermodynamic work, that modify a thermodynamic system containing a constant amount of matter. The law also defines the internal energy of a system, an extensive property for taking account of the balance of heat and work in the system. Energy cannot be created or destroyed, but it can be transformed from one form to another. In an isolated system the sum of all forms of energy is constant.

Physical or chemical properties of materials and systems can often be categorized as being either intensive or extensive, according to how the property changes when the size of the system changes. The terms "intensive and extensive quantities" were introduced into physics by German mathematician Georg Helm in 1898, and by American physicist and chemist Richard C. Tolman in 1917.

The third law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of a closed system at thermodynamic equilibrium approaches a constant value when its temperature approaches absolute zero. This constant value cannot depend on any other parameters characterizing the system, such as pressure or applied magnetic field. At absolute zero the system must be in a state with the minimum possible energy.

In physics, a partition function describes the statistical properties of a system in thermodynamic equilibrium. Partition functions are functions of the thermodynamic state variables, such as the temperature and volume. Most of the aggregate thermodynamic variables of the system, such as the total energy, free energy, entropy, and pressure, can be expressed in terms of the partition function or its derivatives. The partition function is dimensionless.

In mathematics, Frobenius' theorem gives necessary and sufficient conditions for finding a maximal set of independent solutions of an overdetermined system of first-order homogeneous linear partial differential equations. In modern geometric terms, given a family of vector fields, the theorem gives necessary and sufficient integrability conditions for the existence of a foliation by maximal integral manifolds whose tangent bundles are spanned by the given vector fields. The theorem generalizes the existence theorem for ordinary differential equations, which guarantees that a single vector field always gives rise to integral curves; Frobenius gives compatibility conditions under which the integral curves of r vector fields mesh into coordinate grids on r-dimensional integral manifolds. The theorem is foundational in differential topology and calculus on manifolds.

Quantum statistical mechanics is statistical mechanics applied to quantum mechanical systems. In quantum mechanics a statistical ensemble is described by a density operator S, which is a non-negative, self-adjoint, trace-class operator of trace 1 on the Hilbert space H describing the quantum system. This can be shown under various mathematical formalisms for quantum mechanics.

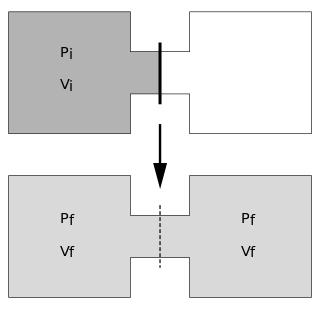

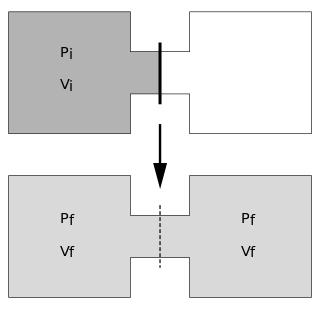

The Joule expansion is an irreversible process in thermodynamics in which a volume of gas is kept in one side of a thermally isolated container, with the other side of the container being evacuated. The partition between the two parts of the container is then opened, and the gas fills the whole container.

In physics, the von Neumann entropy, named after John von Neumann, is a measure of the statistical uncertainty within a description of a quantum system. It extends the concept of Gibbs entropy from classical statistical mechanics to quantum statistical mechanics, and it is the quantum counterpart of the Shannon entropy from classical information theory. For a quantum-mechanical system described by a density matrix ρ, the von Neumann entropy is where denotes the trace and denotes the matrix version of the natural logarithm. If the density matrix ρ is written in a basis of its eigenvectors as then the von Neumann entropy is merely In this form, S can be seen as the Shannon entropy of the eigenvalues, reinterpreted as probabilities.

A thermodynamic cycle consists of linked sequences of thermodynamic processes that involve transfer of heat and work into and out of the system, while varying pressure, temperature, and other state variables within the system, and that eventually returns the system to its initial state. In the process of passing through a cycle, the working fluid (system) may convert heat from a warm source into useful work, and dispose of the remaining heat to a cold sink, thereby acting as a heat engine. Conversely, the cycle may be reversed and use work to move heat from a cold source and transfer it to a warm sink thereby acting as a heat pump. If at every point in the cycle the system is in thermodynamic equilibrium, the cycle is reversible. Whether carried out reversible or irreversibly, the net entropy change of the system is zero, as entropy is a state function.

The principle of minimum energy is essentially a restatement of the second law of thermodynamics. It states that for a closed system, with constant external parameters and entropy, the internal energy will decrease and approach a minimum value at equilibrium. External parameters generally means the volume, but may include other parameters which are specified externally, such as a constant magnetic field.

In classical thermodynamics, entropy is a property of a thermodynamic system that expresses the direction or outcome of spontaneous changes in the system. The term was introduced by Rudolf Clausius in the mid-19th century to explain the relationship of the internal energy that is available or unavailable for transformations in form of heat and work. Entropy predicts that certain processes are irreversible or impossible, despite not violating the conservation of energy. The definition of entropy is central to the establishment of the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of isolated systems cannot decrease with time, as they always tend to arrive at a state of thermodynamic equilibrium, where the entropy is highest. Entropy is therefore also considered to be a measure of disorder in the system.

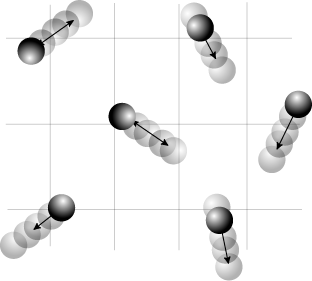

The quantum Heisenberg model, developed by Werner Heisenberg, is a statistical mechanical model used in the study of critical points and phase transitions of magnetic systems, in which the spins of the magnetic systems are treated quantum mechanically. It is related to the prototypical Ising model, where at each site of a lattice, a spin represents a microscopic magnetic dipole to which the magnetic moment is either up or down. Except the coupling between magnetic dipole moments, there is also a multipolar version of Heisenberg model called the multipolar exchange interaction.

In thermodynamics, the fundamental thermodynamic relation are four fundamental equations which demonstrate how four important thermodynamic quantities depend on variables that can be controlled and measured experimentally. Thus, they are essentially equations of state, and using the fundamental equations, experimental data can be used to determine sought-after quantities like G or H (enthalpy). The relation is generally expressed as a microscopic change in internal energy in terms of microscopic changes in entropy, and volume for a closed system in thermal equilibrium in the following way.

In thermodynamics, heat is energy in transfer between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings by modes other than thermodynamic work and transfer of matter. Such modes are microscopic, mainly thermal conduction, radiation, and friction, as distinct from the macroscopic modes, thermodynamic work and transfer of matter. For a closed system, the heat involved in a process is the difference in internal energy between the final and initial states of a system, and subtracting the work done in the process. For a closed system, this is the formulation of the first law of thermodynamics.

A thermodynamic operation is an externally imposed manipulation that affects a thermodynamic system. The change can be either in the connection or wall between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings, or in the value of some variable in the surroundings that is in contact with a wall of the system that allows transfer of the extensive quantity belonging that variable. It is assumed in thermodynamics that the operation is conducted in ignorance of any pertinent microscopic information.

The Gibbs rotational ensemble represents the possible states of a mechanical system in thermal and rotational equilibrium at temperature and angular velocity . The Jaynes procedure can be used to obtain this ensemble. An ensemble is the set of microstates corresponding to a given macrostate.