History

China's links to the Arctic date back to the early 20th century. In 1925, the Republic of China signed the Spitsbergen Treaty, granting access to commercial activity on Svalbard. [5] However, for much of the 20th century, China showed limited interest in the region, focusing instead on Antarctica after the founding of the PRC in 1949. [6]

Scientific engagement grew from the late 1980s with the establishment of the Polar Research Institute of China in Shanghai and the launch of the Chinese Journal of Polar Research in 1988. [7] The first expedition to the North Pole organized by Chinese scientists took place in 1995, and the first expedition organized by the Polar Research Institute of China took place in 1999. [8] China has conducted Arctic expeditions annually since 2016. [8]

China joined the International Arctic Science Committee in 1996, [9] and since 1999 has operated research icebreakers, including the Xue Long and Xue Long 2. In 2004, China established the Yellow River Station in Norway's Svalbard archipelago. While officially devoted to research, analysts have raised concerns about potential dual-use applications. [10] [11]

China hosted the Arctic Science Summit Week in 2005—the first Asian country to do so. By 2010, Chinese policymakers pursued a cautious Arctic approach to avoid alarming the Arctic coastal states, particularly Russia, which had resumed bomber patrols in the region and planted a flag on the seabed in 2007. [12]

In 2012, the Xue Long became the first Chinese vessel to traverse the Northeast Passage. [13] China was granted permanent observer status in the Arctic Council in 2013. [14]

In September 2015, Chinese navy vessels appeared near the coast of Alaska for the first time. [8]

2018 white paper

In January 2018, China released its first Arctic Policy white paper, which remains the most detailed official statement of its regional strategy. [15] The document describes China as a "near-Arctic state," a self-designation that has drawn criticism from Arctic governments and analysts. China argues that its geographic proximity, climatic vulnerability, and economic interests give it a stake in Arctic affairs. [16]

The paper emphasizes four principles: respect, cooperation, win–win outcomes, and sustainability. It highlights climate change, ecological protection, shipping routes, and resource utilization as areas of focus. China also commits to following international law, including the UNCLOS, and acknowledges that non-Arctic states lack territorial sovereignty in the region. [15]

Polar Silk Road

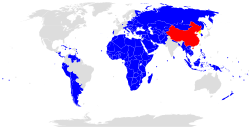

The concept of the "Polar Silk Road" (冰上丝绸之路) was introduced in the 2018 white paper and has since become a central theme in China's Arctic policy. [4] [16] It envisions Arctic shipping lanes as extensions of the Belt and Road Initiative, providing alternative trade routes between Asia, Europe, and North America and also leveraging melting ice for resource extraction. Chinese state-owned enterprises have participated in feasibility studies and infrastructure development along Russia's Arctic coast, including telecommunications projects under the Digital Silk Road. [19]

Supporters argue the Polar Silk Road could lower shipping costs and diversify trade flows, while critics view it as a vehicle for expanding Chinese influence into a region traditionally dominated by Arctic states. [1] [20]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.