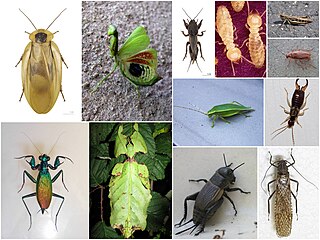

Earwigs make up the insect order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species in 12 families, they are one of the smaller insect orders. Earwigs have characteristic cerci, a pair of forceps-like pincers on their abdomen, and membranous wings folded underneath short, rarely used forewings, hence the scientific order name, "skin wings". Some groups are tiny parasites on mammals and lack the typical pincers. Earwigs are found on all continents except Antarctica.

Forficula auricularia is a species complex comprising the common earwig. It is also known as the European earwig. It is an omnivorous insect belonging to the family Forficulidae. The name earwig comes from the appearance of the hindwings, which are unique in their resemblance to human ears when unfolded. The species name of the common earwig, auricularia, is a specific reference to this feature. The European earwig survives in a variety of environments. It is also a common household insect in North America. They are often considered a household pest because of their tendency to invade crevices in homes and consume pantry foods, though they may also act as beneficial species depending on the circumstances.

Cerci are paired appendages usually on the rear-most segments of many arthropods, including insects and symphylans. Many forms of cerci serve as sensory organs, but some serve as pinching weapons or as organs of copulation. In many insects, they simply may be functionless vestigial structures.

Pygidicranidae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. The family currently contains twelve subfamilies and twenty six genera. Eight of the subfamilies are monotypic, each containing a single genus. Of the subfamilies, both Astreptolabidinae and Burmapygiinae are extinct and known solely from fossils found in Burmese amber. Similarly Archaeosoma, Gallinympha, and Geosoma, which have not been placed into any of the subfamilies, are also known only from fossils. Living members of the family are found in Australia, South Africa, North America, and Asia. The monotypic genus Anataelia, described by Ignacio Bolivar in 1899, is found only on the Canary Islands. As with all members of Neodermaptera, pygidicranids do not have any ocelli. The typical pygidicranid bodyplan includes a small, flattened-looking body, which has a dense covering of bristly hairs (setae). The pair of cerci at the end of the abdomen are symmetrical in structure. The head is broad, with the fourth, fifth and sixth antenna segments (antennomeres) that are not transverse. In general Pygidicranids also have equally sized ventral cervical sclerites, and in having the rearmost sclerite separated from, or only touching the center of the prosternum. Cannibalism of young has been observed in at least one species in the family, Challia hongkongensis, in which an adult female was found eating a still-living nymph of the same species. The same species in a different area has been observed possibly eating fruits or seeds, making the species an omnivore.

Forficulidae is a family of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. There are more than 70 genera and 490 described species in Forficulidae.

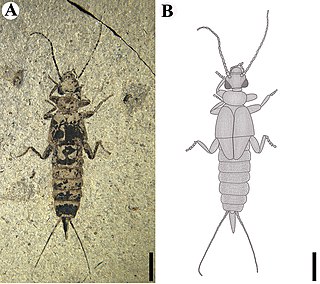

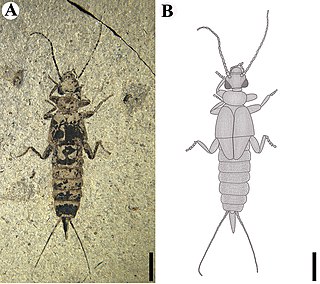

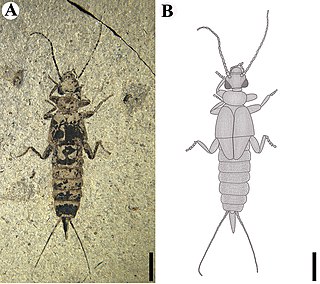

Archidermaptera is an extinct suborder of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. It is one of two extinct suborders of earwigs, and contains two families known only from Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous fossils. The suborder is classified on the basis of general similarities. The Archidermaptera share with modern earwigs tegmenized forewings, though they lack the distinctive forceps-like cerci of modern earwigs, have external ovipositors, and possess ocelli. The grouping has been suggested to be paraphyletic.

Arixeniidae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. Arixeniidae was formerly considered a suborder, Arixeniina, but was reduced in rank to family and included in the new suborder Neodermaptera.

Hemimeridae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. Hemimeridae was formerly considered a suborder, Hemimerina, but was reduced in rank to family and included in the new suborder Neodermaptera.

Protodiplatyidae is an extinct family of earwigs. It is one of three families in the suborder Archidermaptera, alongside Dermapteridae and Turanovia. Species are known from Jurassic and Early Cretaceous fossils and have unsegmented cerci and tarsi with four to five segments.

Microdiplatys is an extinct genus of earwigs, in the family Protodiplatyidae. It is one of only six genera in the family, its family being the only one in the suborder.

Archidermapteron martynovi is an extinct species of earwig, in the genus Archidermapteron, family Protodiplatyidae, the suborder Archidermaptera, the order Dermaptera, and is the only species in the genus Archidermapteron, which simply means "ancient member of the Dermaptera". It had long, segmented cerci unlike modern species of Dermaptera, but tegmina and hind wings that folded up into a "wing package" that are like modern earwigs. The only clear fossil of the species was found in Russia.

Microdiplatys campodeiformis is an extinct species of earwig in the family Protodiplatyidae. It is one of only two species in the genus Microdiplatys, the other being Microdiplatys oculatus.

Microdiplatys oculatus is an extinct species of earwig in the family Protodiplatyidae. It is one of only two species in the genus Microdiplatys, the other being Microdiplatys campodeiformis.

Turanovia incompleta is an extinct species of archidermapteran earwig. It is the only species in the genus Turanovia and family Turanoviidae. It is found in the Middle-Late Jurassic (Callovian-Oxfordian) Karabastau Formation of Kazakhstan.

Labiduridae, whose members are known commonly as striped earwigs, is a relatively large family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera.

Chelisoches morio, the black earwig, is a species of insect in the family Chelisochidae. It is an omnivore that can be found worldwide, however it is most prominent in tropical areas, Pacific islands, the Pacific Northwest, and damp environments. The adults are jet black and can range in size from 18 to 25mm in size, though some have grown to be 36mm. The males cerci are widely separated and serrated compared to the female. The forceps are used for prey capture, defense, fighting and courtship.

Astreptolabis is an extinct genus of earwig in the Dermaptera family Pygidicranidae known from a group of Cretaceous fossils found in Myanmar. The genus contains two described species, Astreptolabis ethirosomatia and Astreptolabis laevis and is the sole member of the subfamily Astreptolabidinae.

Zigrasolabis is an extinct genus of earwig in the family Labiduridae known from Cretaceous fossils found in Myanmar. The genus contains a single described species, Zigrasolabis speciosa.

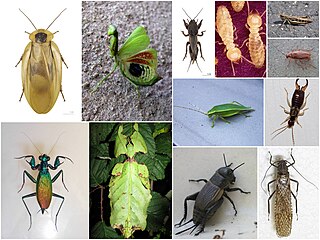

The cohort Polyneoptera is one of the major groups of winged insects, comprising the Orthoptera and all other neopteran insects believed to be more closely related to Orthoptera than to any other insect orders. They were formerly grouped together with the Palaeoptera and Paraneoptera as the Hemimetabola or Exopterygota on the grounds that they have no pupa, the wings gradually developing externally throughout the nymphal stages. Many members of the group have leathery forewings (tegmina) and hindwings with an enlarged anal field (vannus).

Neodermaptera, sometimes called Catadermaptera, is a suborder of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. There are more than 2,000 described species in Neodermaptera.