Diselma archeri is a species of plant of the family Cupressaceae and the sole species in the genus Diselma. It is endemic to the alpine regions of Tasmania's southwest and Central Highlands, on the western coast ranges and Lake St. Clair. It is a monotypic genus restricted to high altitude rainforest and moist alpine heathland. Its distribution mirrors very closely that of other endemic Tasmanian conifers Microcachrys tetragona and Pherosphaera hookeriana.

Asteliaceae is a family of flowering plants, placed in the order Asparagales of the monocots.

Athrotaxis cupressoides, is also known as pencil pine, despite being a species of the family Cupressaceae, and not a member of the pine family. Found either as an erect shrub or as a tree, this species is endemic to Tasmania, Australia. Trees can live for upwards of 1000 years, sustaining a very slow growth rate of approximately 12 mm in diameter per year.

Donatia novae-zelandiae is a species of mat-forming cushion plant, found only in New Zealand and Tasmania. Common names can include New Zealand Cushion or Snow Cushion, however Snow Cushion also refers to Iberis sempervirens. Donatia novae-zelandiae forms dense spirals of thick, leathery leaves, creating a hardy plant that typically exists in alpine and subalpine bioclimatic zones.

Astelia is a genus of flowering plants in the recently named family Asteliaceae. They are rhizomatous tufted perennials native to various islands in the Pacific, Indian, and South Atlantic Oceans, as well as to Australia and to the southernmost tip of South America. A significant number of the known species are endemic to New Zealand. The species generally grow in forests, swamps and amongst low alpine vegetation; occasionally they are epiphytic.

Orites revolutus , also known as narrow-leaf orites, is a Tasmanian endemic plant species in the family Proteaceae. Scottish botanist Robert Brown formally described the species in Transactions of the Linnean Society of London in 1810 from a specimen collected at Lake St Clair. Abundant in alpine and subalpine heath, it is a small to medium shrub 0.5 to 1.5 m tall, with relatively small, blunt leaves with strongly revolute margins. The white flowers grow on terminal spikes during summer. Being proteaceaous, O. revolutus is likely to provide a substantial food source for nectivorous animal species within its range.

Gleichenia alpina, commonly known as alpine coral-fern, is a small fern species that occurs in Tasmania and New Zealand. It grows in alpine and subalpine areas with moist soils and is a part of the Gleichrniaceae family.

Alpine vegetation refers to the zone of vegetation between the altitudinal limit for tree growth and the nival zone. Alpine zones in Tasmania can be difficult to classify owing to Tasmania's maritime climate limiting snow lie to short periods and the presence of a tree line that is not clearly defined.

Eucalyptus pulchella, commonly known as the white peppermint or narrow-leaved peppermint, is a species of small to medium-sized tree that is endemic to Tasmania. it has smooth bark, sometimes with rough fibrous bark on older trees, linear leaves, flower buds in groups of nine to twenty or more, white flowers and cup-shaped to shortened spherical fruit.

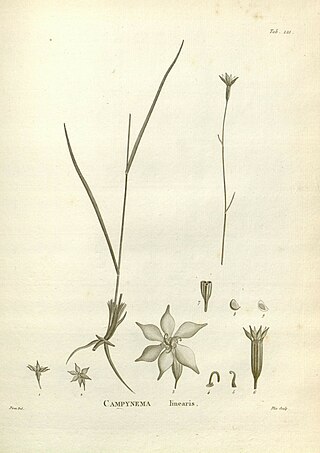

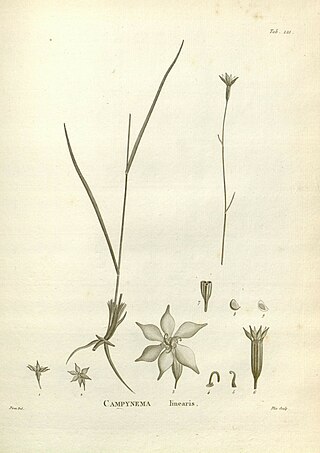

Campynema is a genus in the family Campynemataceae first described in 1805. It contains only one known species (monotypic), Campynema lineare, endemic to the island of Tasmania in Australia. Its closest relative is Campynemanthe, endemic to New Caledonia, sole other genus of the family.

Richea gunnii, the bog candleheath or Gunns richea, is an endemic Tasmanian angiosperm. It is a dicot of the family Ericaceae and is found in Central, Western and North-east Tasmania.

Poa gunnii is a Tasmanian endemic tussock grass considered one of the most abundant and common in alpine and subalpine environments from about 800 m to above 1400 m. However it can be found to near sea level in the south of the island state where a cooler climate is prevalent. The genus Poa belongs to the family Poaceae. Tasmania has 16 native and 6 introduced species of Poa.

Chordifex hookeri is commonly known as woolly buttonrush or cord-rush. It is a rush species of the genus Chordifex in the family Restionaceae. The species is endemic to Tasmania.

Xyris marginata, commonly known as alpine yellow eye, was first collected by German-Australian botanist Ferdinand von Mueller in 1875. Xyris marginata is a monocot in the family Xyridaceae which is endemic to King Island (Tasmania) and Tasmania, commonly growing in button grass moorlands, at altitudes of up to 1070 meters (3,510.5 ft) above sea level.

Chionogentias diemensis is a flowering herbaceous alpine plant in the family Gentianaceae, endemic to the island of Tasmania in Australia. It is commonly known as the Tasmanian mountain gentian. Chionogentias diemensis has been classified into two sub-species: the Tasmanian snow-gentian and the Ben Lomond snow-gentian.

Carpha alpina, commonly known as small flower-rush, is a tufted perennial sedge from the family Cyperaceae. It is found primarily in south-east Australia and both islands of New Zealand, but also in Papua New Guinea.

Abrotanella forsteroides, commonly known as the Tasmanian cushion plant, is an endemic angiosperm of Tasmania, Australia. The plant is a dicot species of the daisy family Asteraceae and can be identified by its bright green and compact cushion like appearance.

Olearia ledifolia, commonly known as rock daisy bush, is a species of flowering plant of the family Asteraceae. It is endemic to Tasmania and found at higher altitudes where it grows as a low, compact bush with tough, leathery leaves and small white and yellow daisy-like "flowers" in summer.

Dracophyllum minimum, commonly known as heath cushionplant or claspleaf heath, is a species of bolster cushion plant endemic to Tasmania, Australia. It is a low growing, highly compacted plant with white flowers, commonly found in alpine areas of the south, centre and west of Tasmania.

Leptecophylla oxycedrus, commonly referred to as coastal pinkberry or crimson berry, is a medium shrub to large tree native to Tasmania and southern Victoria. It is part of the family Ericaceae and has narrow, pointed leaves, white flowers and pale pink fruits. It was previously classified as a subspecies of Leptecophylla juniperina but has since been raised to the specific level in 2017. The species was originally described in 1805 by Jacques Labillardière in Novae Hollandiae plantarum specimen which was published after his voyage through Oceania.