Sources: Solar System

The Sun

As the nearest star, the Sun is the brightest radiation source in most frequencies, down to the radio spectrum at 300 MHz (1 m wavelength). When the Sun is quiet, the galactic background noise dominates at longer wavelengths. During geomagnetic storms, the Sun will dominate even at these low frequencies. [3]

Jupiter

Oscillation of electrons trapped in the magnetosphere of Jupiter produce strong radio signals, particularly bright in the decimeter band.

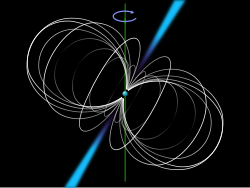

The magnetosphere of Jupiter is responsible for intense episodes of radio emission from the planet's polar regions. Volcanic activity on Jupiter's moon Io injects gas into Jupiter's magnetosphere, producing a torus of particles about the planet. As Io moves through this torus, the interaction generates Alfvén waves that carry ionized matter into the polar regions of Jupiter. As a result, radio waves are generated through a cyclotron maser mechanism, and the energy is transmitted out along a cone-shaped surface. When Earth intersects this cone, the radio emissions from Jupiter can exceed the solar radio output. [4]

Ganymede

In 2021 news outlets reported that scientists, with the Juno spacecraft that orbits Jupiter since 2016, detected an FM radio signal from the moon Ganymede at a location where the planet's magnetic field lines connect with those of its moon. According to the reports these were caused by cyclotron maser instability and were similar to both WiFi-signals and Jupiter's radio emissions. [5] [6] A study about the radio emissions was published in September 2020 [7] but did not describe them to be of FM nature or similar to WiFi signals.[ clarification needed ]