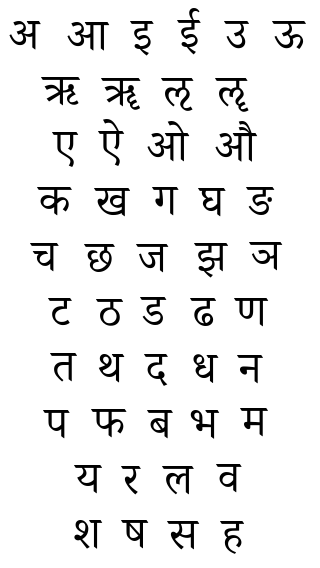

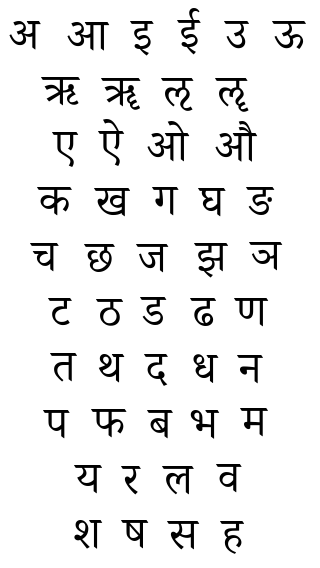

Devanagari is an Indic script used in the northern Indian subcontinent. Also simply called Nāgari, it is a left-to-right abugida, based on the ancient Brāhmi script. It is one of the official scripts of the Republic of India and Nepal. It was developed and in regular use by the 8th century CE and achieved its modern form by 1200 CE. The Devanāgari script, composed of 48 primary characters, including 14 vowels and 34 consonants, is the fourth most widely adopted writing system in the world, being used for over 120 languages.

Marathi is a classical Indo-Aryan language predominantly spoken by Marathi people in the Indian state of Maharashtra and is also spoken in other states like in Goa, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and the territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. It is the official language of Maharashtra, and an additional official language in the state of Goa, where it is used for replies, when requests are received in Marathi. It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India, with 83 million speakers as of 2011. Marathi ranks 13th in the list of languages with most native speakers in the world. Marathi has the third largest number of native speakers in India, after Hindi and Bengali. The language has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indian languages. The major dialects of Marathi are Standard Marathi and the Varhadi Marathi. Marathi was designated as a classical language by the Government of India in October 2024.

Devanagari is an Indic script used for many Indo-Aryan languages of North India and Nepal, including Hindi, Marathi and Nepali, which was the script used to write Classical Sanskrit. There are several somewhat similar methods of transliteration from Devanagari to the Roman script, including the influential and lossless IAST notation. Romanised Devanagari is also called Romanagari.

The phoneme inventory of the Marathi language is similar to that of many other Indo-Aryan languages. An IPA chart of all contrastive sounds in Marathi is provided below.

WX notation is a transliteration scheme for representing Indian languages in ASCII. This scheme originated at IIT Kanpur for computational processing of Indian languages, and is widely used among the natural language processing (NLP) community in India. The notation is used, for example, in a textbook on NLP from IIT Kanpur. The salient features of this transliteration scheme are: Every consonant and every vowel has a single mapping into Roman. Hence it is a prefix code, advantageous from a computation point of view. Typically the small case letters are used for un-aspirated consonants and short vowels while the capital case letters are used for aspirated consonants and long vowels. While the retroflexed voiceless and voiced consonants are mapped to 't, T, d and D', the dentals are mapped to 'w, W, x and X'. Hence the name of the scheme "WX", referring to the idiosyncratic mapping. Ubuntu Linux provides a keyboard support for WX notation.

Ṅa is the fifth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, It is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ca is the sixth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, ca is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter , which is probably derived from the North Semitic letter tsade, with an inversion seen in several other derivatives, after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Cha is the seventh consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, cha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter , which is probably derived from the Aramaic letter ("Q") after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Jha is the ninth consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, jha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ña or Nya is the tenth consonant of Indic abugidas. It is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter .

Ṭa is a consonant of Indic abugidas. It is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . As with the other retroflex consonants, ṭa is absent from most scripts not used for a language of India.

This page describes the grammar of Maithili language, which has a complex verbal system, nominal declension with a few inflections, and extensive use of honoroficity. It is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Maithili people and is spoken in the Indian state of Bihar with some speakers in Jharkhand and nearby states.The language has a large number of speakers in Nepal too, which is second in number of speakers after Bihar.

Ṭha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ṭha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . As with the other cerebral consonants, ṭha is not found in most scripts for Tai, Sino-Tibetan, and other non-Indic languages, except for a few scripts, which retain these letters for transcribing Sanskrit religious terms.

Ḍha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ḍha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . As with the other cerebral consonants, ḍha is not found in most scripts for Tai, Sino-Tibetan, and other non-Indic languages, except for a few scripts, which retain these letters for transcribing Sanskrit religious terms.

Tha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, tha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Da is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Da is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Pha is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Pha is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

Ra is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, Ra is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . Most Indic scripts have differing forms of Ra when used in combination with other consonants, including subjoined and repha forms. Some of these are encoded in computer text as separate characters, while others are generated dynamically using conjunct shaping with a virama.

La is a consonant of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, La is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter .

A is a vowel of Indic abugidas. In modern Indic scripts, A is derived from the early "Ashoka" Brahmi letter after having gone through the Gupta letter . Bare consonants without a modifying vowel sign have the "A" vowel inherently, and thus there is no modifier sign for "A" in Indic scripts.