Castle Rising is a ruined medieval fortification in the village of Castle Rising, Norfolk, England. It was built soon after 1138 by William d'Aubigny II, who had risen through the ranks of the Anglo-Norman nobility to become the Earl of Arundel. With his new wealth, he constructed Castle Rising and its surrounding deer park, a combination of fortress and palatial hunting lodge. It was inherited by William's descendants before passing into the hands of the de Montalt family in 1243. The Montalts later sold the castle to Queen Isabella, who lived there after her fall from power in 1330. Isabella extended the castle buildings and enjoyed a regal lifestyle, entertaining her son, Edward III, on several occasions. After her death, it was granted to Edward, the Black Prince, to form part of the Duchy of Cornwall.

Framlingham Castle is a castle in the market town of Framlingham, Suffolk, England. An early motte and bailey or ringwork Norman castle was built on the Framlingham site by 1148, but this was destroyed (slighted) by Henry II of England in the aftermath of the Revolt of 1173–1174. Its replacement, constructed by Roger Bigod, the Earl of Norfolk, was unusual for the time in having no central keep, but instead using a curtain wall with thirteen mural towers to defend the centre of the castle. Despite this, the castle was successfully taken by King John in 1216 after a short siege. By the end of the 13th century, Framlingham had become a luxurious home, surrounded by extensive parkland used for hunting.

Castles have played an important military, economic and social role in Great Britain and Ireland since their introduction following the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Although a small number of castles had been built in England in the 1050s, the Normans began to build motte and bailey and ringwork castles in large numbers to control their newly occupied territories in England and the Welsh Marches. During the 12th century the Normans began to build more castles in stone – with characteristic square keep – that played both military and political roles. Royal castles were used to control key towns and the economically important forests, while baronial castles were used by the Norman lords to control their widespread estates. David I invited Anglo-Norman lords into Scotland in the early 12th century to help him colonise and control areas of his kingdom such as Galloway; the new lords brought castle technologies with them and wooden castles began to be established over the south of the kingdom. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 1170s, under Henry II, castles were established there too.

Warwick Castle is a medieval castle developed from a wooden fort, originally built by William the Conqueror during 1068. Warwick is the county town of Warwickshire, England, situated on a meander of the River Avon. The original wooden motte-and-bailey castle was rebuilt in stone during the 12th century. During the Hundred Years War, the facade opposite the town was refortified, resulting in one of the most recognisable examples of 14th-century military architecture. It was used as a stronghold until the early 17th century, when it was granted to Sir Fulke Greville by James I in 1604. Greville converted it to a country house, and it was owned by the Greville family until 1978, when it was bought by the Tussauds Group.

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy to build with unskilled labour, but still militarily formidable, these castles were built across northern Europe from the 10th century onwards, spreading from Normandy and Anjou in France, into the Holy Roman Empire, as well as the Low Countries it controlled, in the 11th century, when these castles were popularized in the area that became the Netherlands. The Normans introduced the design into England and Wales. Motte-and-bailey castles were adopted in Scotland, Ireland, and Denmark in the 12th and 13th centuries. By the end of the 13th century, the design was largely superseded by alternative forms of fortification, but the earthworks remain a prominent feature in many countries.

A keep is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word keep, but usually consider it to refer to large towers in castles that were fortified residences, used as a refuge of last resort should the rest of the castle fall to an adversary. The first keeps were made of timber and formed a key part of the motte-and-bailey castles that emerged in Normandy and Anjou during the 10th century; the design spread to England, Portugal, south Italy and Sicily. As a result of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, use spread into Wales during the second half of the 11th century and into Ireland in the 1170s. The Anglo-Normans and French rulers began to build stone keeps during the 10th and 11th centuries, including Norman keeps, with a square or rectangular design, and circular shell keeps. Stone keeps carried considerable political as well as military importance and could take a decade or more to build.

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined medieval castle on the western side of central Oxford in Oxfordshire, England. Most of the original moated, wooden motte and bailey castle was replaced in stone in the late 12th or early 13th century and the castle played an important role in the conflict of the Anarchy. In the 14th century the military value of the castle diminished and the site became used primarily for county administration and as a prison. The surviving rectangular St George's Tower is now believed to pre-date the remainder of the castle and be a watch tower associated with the original Saxon west gate of the city.

Cambridge Castle, locally also known as Castle Mound, is located in Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England. Originally built after the Norman conquest to control the strategically important route to the north of England, it played a role in the conflicts of the Anarchy, the First and Second Barons' Wars. Hugely expanded by Edward I, the castle then fell rapidly into disuse in the late medieval era, its stonework recycled for building purposes in the surrounding colleges. Cambridge Castle was refortified during the English Civil War but once again fell into disuse, used primarily as the county gaol. The castle gaol was finally demolished in 1842, with a new prison built in the castle bailey. This prison was demolished in 1932, replaced with the modern Shire Hall, and only the castle motte and limited earthworks still stand. The site is open to the public daily and offers views over the historic buildings of the city.

Sir Falkes de Bréauté was an Anglo-Norman soldier who earned high office by loyally serving first King John and later King Henry III in the First Barons' War. He played a key role in the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1217. He attempted to rival Hubert de Burgh, and as a result fell from power in 1224. His "heraldic device" is now popularly said to have been a griffin, although his coat of arms as depicted by Matthew Paris in his Chronica Majora was Gules, a cinquefoil argent.

Wallingford Castle is a medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire, adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Saxon burgh, it grew to become what historian Nicholas Brooks has described as "one of the most powerful royal castles of the 12th and 13th centuries". Held for the Empress Matilda during the civil war years of the Anarchy, it survived multiple sieges and was never taken. Over the next two centuries it became a luxurious castle, used by royalty and their immediate family. After being abandoned as a royal residence by Henry VIII, the castle fell into decline. Refortified during the English Civil War, it was eventually slighted, i.e. deliberately destroyed, after being captured by Parliamentary forces after a long siege. The site was subsequently left relatively undeveloped, and the limited remains of the castle walls and the considerable earthworks are now open to the public.

Castle Acre Castle and town walls are a set of ruined medieval defences built in the village of Castle Acre, Norfolk. The castle was built soon after the Norman Conquest by William de Warenne, the Earl of Surrey, at the intersection of the River Nar and the Peddars Way. William constructed a motte-and-bailey castle during the 1070s, protected by large earthwork ramparts, with a large country house in the centre of the motte. Soon after, a small community of Cluniac monks were given the castle's chapel in the outer bailey; under William, the second earl, the order was given land and estates to establish Castle Acre Priory alongside the castle. A deer park was created nearby for hunting.

Clare Castle is a high-mounted ruinous medieval castle in the parish and former manor of Clare in Suffolk, England, anciently the caput of a feudal barony. It was built shortly after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 by Richard Fitz Gilbert, having high motte and bailey and later improved in stone. In the 14th century it was the seat of Elizabeth de Clare, one of the wealthiest women in England, who maintained a substantial household there. The castle passed into the hands of the Crown and by 1600 was disused. The ruins are an unusually tall earthen motte surmounted by tall remnants of a wall and of the round tower, with large grassland or near-rubble gaps on several of their sides. It was damaged by an alternate line of the Great Eastern Railway in 1867, the rails of which have been removed.

Eaton Socon Castle was a Norman fortification. It was constructed next to the River Great Ouse in what is now Eaton Socon, Cambridgeshire, England.

Eye Castle is a motte and bailey medieval castle with a prominent Victorian addition in the town of Eye, Suffolk. Built shortly after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the castle was sacked and largely destroyed in 1265. Sir Edward Kerrison built a stone house on the motte in 1844: the house later decayed into ruin, becoming known as Kerrison's Folly in subsequent years.

Luton Castle was a 12th-century castle in the town of Luton, in the county of Bedfordshire, England.

Corfe Castle is a fortification standing above the village of the same name on the Isle of Purbeck peninsula in the English county of Dorset. Built by William the Conqueror, the castle dates to the 11th century and commands a gap in the Purbeck Hills on the route between Wareham and Swanage. The first phase was one of the earliest castles in England to be built at least partly using stone when the majority were built with earth and timber. Corfe Castle underwent major structural changes in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Worcester Castle was a Norman fortification built between 1068 and 1069 in Worcester, England by Urse d'Abetot on behalf of William the Conqueror. The castle had a motte-and-bailey design and was located on the south side of the old Anglo-Saxon city, cutting into the grounds of Worcester Cathedral. Royal castles were owned by the king and maintained on his behalf by an appointed constable. At Worcester that role was passed down through the local Beauchamp family on a hereditary basis, giving them permanent control of the castle and considerable power within the city. The castle played an important part in the wars of the 12th and early 13th century, including the Anarchy and the First Barons' War.

Berkhamsted Castle is a Norman motte-and-bailey castle in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. The castle was built to obtain control of a key route between London and the Midlands during the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century. Robert of Mortain, William the Conqueror's half brother, was probably responsible for managing its construction, after which he became the castle's owner. The castle was surrounded by protective earthworks and a deer park for hunting. The castle became a new administrative centre of the former Anglo-Saxon settlement of Berkhamsted. Subsequent kings granted the castle to their chancellors. The castle was substantially expanded in the mid-12th century, probably by Thomas Becket.

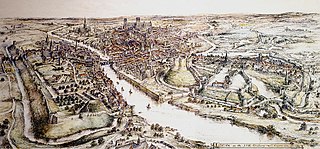

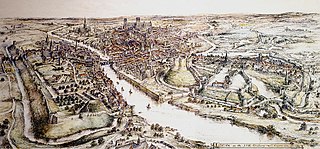

Southampton Castle was located in the town of Southampton in Hampshire, England. Constructed after the Norman conquest of England, it was located in the north-west corner of the town overlooking the River Test, initially as a wooden motte and bailey design. By the late 12th century the royal castle had been largely converted to stone, playing an important part in the wine trade conducted through the Southampton docks. By the end of the 13th century the castle was in decline, but the threat of French raids in the 1370s led Richard II to undertake extensive rebuilding. The result was a powerfully defended castle, one of the first in England to be equipped with cannon. The castle declined again in the 16th century and was sold off to property speculators in 1618. After being used for various purposes, including the construction of a Gothic mansion in the early 19th century, the site was flattened and largely redeveloped. Only a few elements of the castle still remain visible in Southampton.