Herbicides, also commonly known as weed killers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds. Selective herbicides control specific weed species while leaving the desired crop relatively unharmed, while non-selective herbicides can be used to clear waste ground, industrial and construction sites, railways and railway embankments as they kill all plant material with which they come into contact. Apart from selective/non-selective, other important distinctions include persistence, means of uptake, and mechanism of action. Historically, products such as common salt and other metal salts were used as herbicides, however, these have gradually fallen out of favor, and in some countries, a number of these are banned due to their persistence in soil, and toxicity and groundwater contamination concerns. Herbicides have also been used in warfare and conflict.

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, whether pest animals such as insects and mites, weeds, or pathogens affecting animals or plants by using other organisms. It relies on predation, parasitism, herbivory, or other natural mechanisms, but typically also involves an active human management role. It can be an important component of integrated pest management (IPM) programs.

Weed control is a type of pest control, which attempts to stop or reduce growth of weeds, especially noxious weeds, with the aim of reducing their competition with desired flora and fauna including domesticated plants and livestock, and in natural settings preventing non native species competing with native species.

Bromus tectorum, known as downy brome, drooping brome or cheatgrass, is a winter annual grass native to Europe, southwestern Asia, and northern Africa, but has become invasive in many other areas. It now is present in most of Europe, southern Russia, Japan, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Iceland, Greenland, North America and western Central Asia. In the eastern US B. tectorum is common along roadsides and as a crop weed, but usually does not dominate an ecosystem. It has become a dominant species in the Intermountain West and parts of Canada, and displays especially invasive behavior in the sagebrush steppe ecosystems where it has been listed as noxious weed. B. tectorum often enters the site in an area that has been disturbed, and then quickly expands into the surrounding area through its rapid growth and prolific seed production.

Centaurea diffusa, also known as diffuse knapweed, white knapweed or tumble knapweed, is a member of the genus Centaurea in the family Asteraceae. This species is common throughout western North America but is not actually native to the North American continent, but to the eastern Mediterranean.

MCPA is a widely used phenoxy herbicide introduced in 1945. It selectively controls broad-leaf weeds in pasture and cereal crops. The mode of action of MCPA is as an auxin, which are growth hormones that naturally exist in plants.

A biopesticide is a biological substance or organism that damages, kills, or repels organisms seen as pests. Biological pest management intervention involves predatory, parasitic, or chemical relationships.

Centaurea solstitialis, the yellow star-thistle, is a species of thorny plant in the genus Centaurea, which is part of the family Asteraceae. A winter annual, it is native to the Mediterranean Basin region and invasive in many other places. It is also known as golden starthistle, yellow cockspur and St. Barnaby's thistle.

Phenoxy herbicides are two families of chemicals that have been developed as commercially important herbicides, widely used in agriculture. They share the part structure of phenoxyacetic acid.

Hippodamia convergens, commonly known as the convergent lady beetle, is one of the most common lady beetles in North America and is found throughout the continent. Aphids form their main diet and they are used for the biological control of these pests.

Dan James Pantone is an American ecologist and conservationist with a Ph.D. from the University of California, Davis. A former professor at Texas A&M University, Dr. Pantone is a researcher who has published numerous refereed articles on agroecology and sustainable agriculture. In addition, he is a specialist in Geographical Information Systems (GIS) which he has used to help conserve endangered species. Dr. Pantone has established his broad experience in numerous scientific disciplines by publishing diverse articles ranging from the biological control of pests to the conservation biology of endangered species.

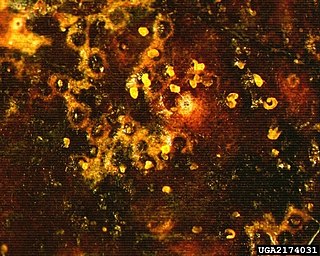

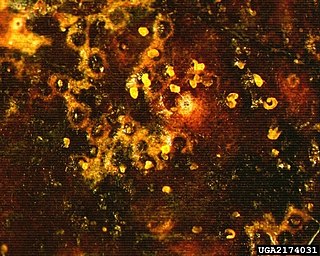

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is a plant pathogenic fungus and can cause a disease called white mold if conditions are conducive. S. sclerotiorum can also be known as cottony rot, watery soft rot, stem rot, drop, crown rot and blossom blight. A key characteristic of this pathogen is its ability to produce black resting structures known as sclerotia and white fuzzy growths of mycelium on the plant it infects. These sclerotia give rise to a fruiting body in the spring that produces spores in a sac which is why fungi in this class are called sac fungi (Ascomycota). This pathogen can occur on many continents and has a wide host range of plants. When S. sclerotiorum is onset in the field by favorable environmental conditions, losses can be great and control measures should be considered.

Drechslera avenacea is a fungal plant pathogen.

Agricultural pollution refers to biotic and abiotic byproducts of farming practices that result in contamination or degradation of the environment and surrounding ecosystems, and/or cause injury to humans and their economic interests. The pollution may come from a variety of sources, ranging from point source water pollution to more diffuse, landscape-level causes, also known as non-point source pollution and air pollution. Once in the environment these pollutants can have both direct effects in surrounding ecosystems, i.e. killing local wildlife or contaminating drinking water, and downstream effects such as dead zones caused by agricultural runoff is concentrated in large water bodies.

Striga hermonthica, commonly known as purple witchweed or giant witchweed, is a hemiparasitic plant that belongs to the family Orobanchaceae. It is devastating to major crops such as sorghum and rice. In sub-Saharan Africa, apart from sorghum and rice, it also infests maize, pearl millet, and sugar cane.

Parthenium hysterophorus is a species of flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. It is native to the American tropics. Common names include Santa-Maria, Santa Maria feverfew, whitetop weed, and famine weed. In India, it is locally known as carrot grass, congress grass or gajar ghas or dhanura. It is a common invasive species in India, Australia, and parts of Africa.

Calophoma clematidina is a fungal plant pathogen and the most common cause of the disease clematis wilt affecting large-flowered varieties of Clematis. Symptoms of infection include leaf spotting, wilting of leaves, stems or the whole plant and internal blackening of the stem, often at soil level. Infected plants growing in containers may also develop root rot.

In Australia, Mimosa pigra has been declared a noxious weed or given similar status under various weed or quarantine Acts. It has been ranked as the tenth most problematic weed and is listed on the Weeds of National Significance. It is currently restricted to the Northern Territory where it infests approximately 80,000 hectares of coastal floodplain.

Centaurea stoebe, the spotted knapweed or panicled knapweed, is a species of Centaurea native to eastern Europe, although it has spread to North America, where it is considered an invasive species. It forms a tumbleweed, helping to increase the species' reach, and the seeds are also enabled by a feathery pappus.

Karen Bailey is a retired research scientist who specialized in plant pathology and biopesticide development at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Her research focused on developing alternatives to synthetic pesticides and improving plant health through integrated pest management strategies. She is internationally recognized for her expertise on soil-borne pathogens and biological control, and she has more than 250 publications, 23 patents, and 7 inventions disclosures in progress.