A pidgin, or pidgin language, is a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from several languages. It is most commonly employed in situations such as trade, or where both groups speak languages different from the language of the country in which they reside.

Tok Pisin, often referred to by English speakers as New Guinea Pidgin or simply Pidgin, is a creole language spoken throughout Papua New Guinea. It is an official language of Papua New Guinea and the most widely used language in the country. However, in parts of the southern provinces of Western, Gulf, Central, Oro, and Milne Bay, the use of Tok Pisin has a shorter history and is less universal, especially among older people.

Bislama is an English-based creole language. It is the national language of Vanuatu, and one of the three official languages of the country, the other ones being English and French. Bislama is the first language of many of the "Urban ni-Vanuatu" and the second language of much of the rest of the country's residents. The lyrics of "Yumi, Yumi, Yumi", the country's national anthem, are composed in Bislama.

This glossary of names for the British include nicknames and terms, including affectionate ones, neutral ones, and derogatory ones to describe British people, Irish People and more specifically English, Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish people. Many of these terms may vary between offensive, derogatory, neutral and affectionate depending on a complex combination of tone, facial expression, context, usage, speaker and shared past history.

Bollocks is a word of Middle English origin meaning "testicles". The word is often used in British English and Irish English in a multitude of negative ways; it most commonly appears as a noun meaning "rubbish" or "nonsense", an expletive following a minor accident or misfortune, or an adjective to describe something that is of poor quality or useless. It is also used in common phrases like "bollocks to this", which is said when quitting a task or job that is too difficult or negative, and "that's a load of old bollocks", which generally indicates contempt for a certain subject or opinion. Conversely, the word also appears in positive phrases such as "the dog's bollocks" or more simply "the bollocks", which will refer to something which is admired or well-respected.

Torres Strait Creole, also known as Torres Strait Pidgin, Brokan/Broken, Cape York Creole, Lockhart Creole, Kriol, Papuan, Broken English, Blaikman, Big Thap, Pizin, and Ailan Tok, is an English-based creole language spoken on several Torres Strait Islands of Queensland, Australia; Northern Cape York; and south-western coastal Papua New Guinea (PNG).

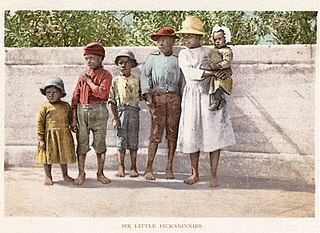

Pickaninny is a pidgin word for a small child, possibly derived from the Portuguese pequenino. It has been used as a racial slur for African American children and a pejorative term for Aboriginal children of the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand. It can also refer to a derogatory caricature of a dark-skinned child of African descent.

"Feck" is a word that has several vernacular meanings and variations in Irish English, Scots, and Middle English.

Club Buggery is an Australian television series made in the 1990s. It was created and performed by Australian comedy duo Roy and HG and broadcast on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) network in 1996 and 1997.

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of its capital city, Port Moresby.

Bugger is a slang expletive used in vernacular English. Bugger may also refer to:

The Spanish language employs a wide range of swear words that vary between Spanish speaking nations and in regions and subcultures of each nation. Idiomatic expressions, particularly profanity, are not always directly translatable into other languages, and so most of the English translations offered in this article are very rough and most likely do not reflect the full meaning of the expression they intend to translate.[c]

Profanity in Finnish is used in the form of intensifiers, adjectives, adverbs and particles, and is based on varying taboos, with religious vulgarity being very prominent. It often uses aggressive mood which involves omission of the negative verb ei while implying its meaning with a swear word.

The Tolai language, or Kuanua, is spoken by the Tolai people of Papua New Guinea, who live on the Gazelle Peninsula in East New Britain Province.

To kick the bucket is an English idiom considered a euphemistic, informal, or slang term meaning "to die". Its origin remains unclear, though there have been several theories.

Kastom is a pidgin word used to refer to traditional culture, including religion, economics, art and magic in Melanesia.

No worries is an expression in English meaning "do not worry about that", "that's all right", "forget about it" or "sure thing". It is similar to the American English "no problem". It is widely used in Australian and New Zealand speech and represents a feeling of friendliness, good humour, optimism and "mateship" in Australian culture, and has been called the national motto of Australia.

Pijin is a language spoken in Solomon Islands. It is closely related to Tok Pisin of Papua New Guinea and Bislama of Vanuatu; the three varieties are sometimes considered to be dialects of a single Melanesian Pidgin language. It is also related to Torres Strait Creole of Torres Strait, though more distantly.

An expletive attributive is an adjective or adverb that does not contribute to the meaning of a sentence, but is used to intensify its emotional force. Often such words or phrases are regarded as profanity or "bad language", though there are also inoffensive expletive attributives. The word is derived from the Latin verb explere, meaning "to fill", and it was originally introduced into English in the 17th century for various kinds of padding.