The history of Grenada in the Caribbean, part of the Lesser Antilles group of islands, covers a period from the earliest human settlements to the establishment of the contemporary nationstate of Grenada. First settled by indigenous peoples, Grenada by the time of European contact was inhabited by the Caribs. French colonists killed most of the Caribs on the island and established plantations on the island, eventually importing African slaves to work on the sugar plantations.

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe,, was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations against the French coast as part of Britain's policy of naval descents during the Seven Years' War. He also took part, as a naval captain, in the decisive British naval victory at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in November 1759.

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, Count of Estaing was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the British during the Seven Years' War. Naval exploits during the latter war prompted him to change branches of service, and he transferred to the French Navy.

George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney, was an Anglo-Irish statesman, colonial administrator and diplomat who served as the governor of Grenada, Madras and the British-occupied Cape Colony. He is often remembered for his observation following Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War and subsequent territorial expansion at the Treaty of Paris that Britain now controlled "a vast Empire, on which the sun never sets".

The American Revolutionary War saw a series of battles involving naval forces of the British Royal Navy and the Continental Navy from 1775, and of the French Navy from 1778 onwards. Although the British enjoyed more numerical victories, these battles culminated in the surrender of the British Army force of Lieutenant-General Earl Charles Cornwallis, an event that led directly to the beginning of serious peace negotiations and the eventual end of the war. From the start of the hostilities, the British North American station under Vice-Admiral Samuel Graves blockaded the major colonial ports and carried raids against patriot communities. Colonial forces could do little to stop these developments due to British naval supremacy. In 1777, colonial privateers made raids into British waters capturing merchant ships, which they took into French and Spanish ports, although both were officially neutral. Seeking to challenge Britain, France signed two treaties with America in February 1778, but stopped short of declaring war on Britain. The risk of a French invasion forced the British to concentrate its forces in the English Channel, leaving its forces in North America vulnerable to attacks.

The siege of Savannah or the Second Battle of Savannah was an encounter of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) in 1779. The year before, the city of Savannah, Georgia, had been captured by a British expeditionary corps under Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Campbell. The siege itself consisted of a joint Franco-American attempt to retake Savannah, from September 16 to October 18, 1779. On October 9 a major assault against the British siege works failed. During the attack, Polish nobleman Count Casimir Pulaski, leading the combined cavalry forces on the American side, was mortally wounded. With the failure of the joint attack, the siege was abandoned, and the British remained in control of Savannah until July 1782, near the end of the war.

Admiral of the Red Sir William Cornwallis, was a Royal Navy officer. He was the brother of Charles Cornwallis, the 1st Marquess Cornwallis, British commander at the siege of Yorktown. Cornwallis took part in a number of decisive battles including the siege of Louisbourg in 1758, when he was 14, and the Battle of the Saintes but is best known as a friend of Lord Nelson and as the commander-in-chief of the Channel Fleet during the Napoleonic Wars. He is depicted in the Horatio Hornblower novel, Hornblower and the Hotspur.

The Battle of Grenada took place on 6 July 1779 during the American Revolutionary War in the West Indies between the British Royal Navy and the French Navy, just off the coast of Grenada. The British fleet of Admiral John Byron had sailed in an attempt to relieve Grenada, which the French forces of the Comte D'Estaing had just captured.

The Battle of Martinique, also known as the Combat de la Dominique, took place on 17 April 1780 during the American Revolutionary War in the West Indies between the British Royal Navy and the French Navy.

The Battle of St. Lucia or the Battle of the Cul de Sac was a naval battle fought off the island of St. Lucia in the West Indies during the American Revolutionary War on 15 December 1778, between the British Royal Navy and the French Navy.

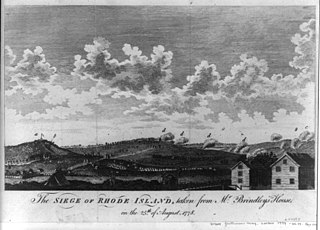

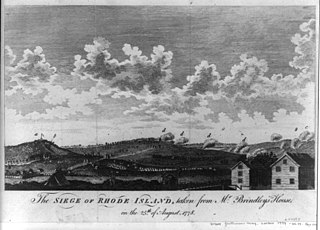

The Battle of Rhode Island took place on August 29, 1778. Continental Army and Militia forces under the command of Major General John Sullivan had been besieging the British forces in Newport, Rhode Island, which is situated on Aquidneck Island, but they had finally abandoned their siege and were withdrawing to the northern part of the island. The British forces then sortied, supported by recently arrived Royal Navy ships, and they attacked the retreating Americans. The battle ended inconclusively, but the Continental forces withdrew to the mainland and left Aquidneck Island in British hands.

The Battle of Cape Henry was a naval battle in the American War of Independence which took place near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 16 March 1781 between a British squadron led by Vice Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot and a French fleet under Admiral Charles René Dominique Sochet, Chevalier Destouches. Destouches, based in Newport, Rhode Island, had sailed for the Chesapeake as part of a joint operation with the Continental Army to oppose the British army of Brigadier General Benedict Arnold that was active in Virginia.

HMS Boyne was a 70-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Plymouth Dockyard to the draught specified in the 1745 Establishment as amended in 1754, and launched on 31 May 1766. She was first commissioned for the Falkland Crisis of 1770 after which, in 1774, she sailed for North America. From March 1776, she served in the English Channel then, in May 1778, she was sent to the West Indies where she took part in the battles of St Lucia, Grenada and Martinique. In November 1780, Boyne returned home, where she was fitted for ordinary at Plymouth. In May 1783, she was broken up.

Arthur Dillon (1750–1794) was an Irish Catholic aristocrat born in England who inherited the ownership of a regiment that served France under the Ancien Régime during the American Revolutionary War and then the French First Republic during the War of the First Coalition. After serving in political positions during the early years of the revolution, he was executed in Paris as a royalist during the Reign of Terror in 1794.

The Invasion of Tobago was a French invasion of the British-held island of Tobago during the Anglo-French War. On May 24, 1781, the fleet of Comte de Grasse landed troops on the island under the command of General Marquis de Bouillé. By June 2, 1781, they had successfully gained control of the island.

Afro-Grenadians or Black Grenadians are Grenadian people of largely African descent. This term is not generally recognised by Grenadians or indeed Caribbeans. They usually refer to themselves simply as Black or possibly Black Caribbean. The term was first coined by an African Americans history professor, John Henrik Clarke (1915–1998), in his piece entitled A Note on Racism in History. The term may also refer to a Grenadian of African ancestry. Social interpretations of race are mutable rather than deterministic and neither physical appearance nor ancestry are used straightforwardly to determine whether a person is considered a Black Grenadian. According to the 2012 Census, 82% of Grenada's population is Black, 13% is mixed European and black and 2% is of Indian origin.

The Capture of Saint Vincent was a French invasion that took place between 16 and 18 June 1779 during the American Revolutionary War. A French force commander named Charles-Marie de Trolong du Rumain landed on the island of Saint Vincent in the West Indies and quickly took over much of the British-controlled part of the island, assisted by local Black Caribs who held the northern part of the island.

The Capture of St Lucia was the result of a campaign from 18–28 December 1778 by British land and naval forces to take over the island, which was a French colony. Britain's actions followed the capture of the British-controlled island of Dominica by French forces in a surprise invasion in September 1778. During the Battle of St. Lucia, the British fleet defeated a French fleet sent to reinforce the island. A few days later French troops were soundly defeated by British troops during the Battle of Morne de la Vigie. Realising that another British fleet would soon arrive with reinforcements, the French garrison surrendered. The remaining French troops were evacuated, and the French fleet returned to Martinique, another French colony. St. Lucia stayed in the hands of the British.

Fédon's rebellion was an uprising against British rule in Grenada. Although a significant number of slaves were involved, they fought on both sides. Predominantly led by free mixed-race French-speakers, the stated purpose was to create a black republic as had already occurred in neighbouring Haiti rather than to free slaves, so it is not properly called a slave rebellion, although freedom of the slaves would have been a consequence of its success. Under the leadership of Julien Fédon, owner of a plantation in the mountainous interior of the island, and encouraged by French Revolutionary leaders on Guadeloupe, the rebels seized control of most of the island, but were eventually defeated by a military expedition led by General Ralph Abercromby.

The Anglo-French War, also known as the War of 1778 or the Bourbon War in Britain, was a military conflict fought between France and Great Britain, sometimes with their respective allies, between 1778 and 1783. As a consequence, Great Britain was forced to divert resources used to fight the American War of Independence to theatres in Europe, India and the West Indies, and to rely on what turned out to be the chimera of Loyalist support in its North American operations. From 1778 to 1783, with or without their allies, France and Britain fought over dominance in the English Channel, the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and the Caribbean.