The Mariner program was conducted by the American space agency NASA to explore other planets. Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) designed and built 10 robotic interplanetary probes named Mariner to explore the inner Solar System – visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for additional close observations.

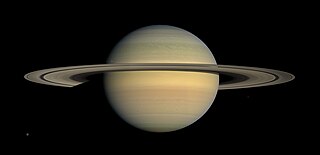

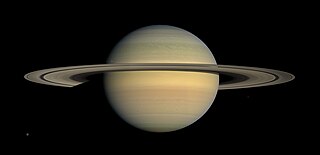

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about nine times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 times more massive. Even though Saturn is almost as big as Jupiter, Saturn has less than a third its mass. Saturn orbits the Sun at a distance of 9.59 AU (1,434 million km), with an orbital period of 29.45 years.

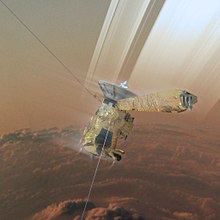

Cassini–Huygens, commonly called Cassini, was a space-research mission by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) to send a space probe to study the planet Saturn and its system, including its rings and natural satellites. The Flagship-class robotic spacecraft comprised both NASA's Cassini space probe and ESA's Huygens lander, which landed on Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Cassini was the fourth space probe to visit Saturn and the first to enter its orbit, where it stayed from 2004 to 2017. The two craft took their names from the astronomers Giovanni Cassini and Christiaan Huygens.

Aerobraking is a spaceflight maneuver that reduces the high point of an elliptical orbit (apoapsis) by flying the vehicle through the atmosphere at the low point of the orbit (periapsis). The resulting drag slows the spacecraft. Aerobraking is used when a spacecraft requires a low orbit after arriving at a body with an atmosphere, as it requires less fuel than using propulsion to slow down.

A gravity assist, gravity assist maneuver, swing-by, or generally a gravitational slingshot in orbital mechanics, is a type of spaceflight flyby which makes use of the relative movement and gravity of a planet or other astronomical object to alter the path and speed of a spacecraft, typically to save propellant and reduce expense.

Huygens was an atmospheric entry robotic space probe that landed successfully on Saturn's moon Titan in 2005. Built and operated by the European Space Agency (ESA), launched by NASA, it was part of the Cassini–Huygens mission and became the first spacecraft to land on Titan and the farthest landing from Earth a spacecraft has ever made. The probe was named after the 17th-century Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens, who discovered Titan in 1655.

The Mars Climate Orbiter was a robotic space probe launched by NASA on December 11, 1998, to study the Martian climate, Martian atmosphere, and surface changes and to act as the communications relay in the Mars Surveyor '98 program for Mars Polar Lander. However, on September 23, 1999, communication with the spacecraft was permanently lost as it went into orbital insertion. The spacecraft encountered Mars on a trajectory that brought it too close to the planet, and it was destroyed in the atmosphere. An investigation attributed the failure to a measurement mismatch between two measurement systems: SI units (metric) by NASA and US customary units by spacecraft builder Lockheed Martin.

This article provides a timeline of the Cassini–Huygens mission. Cassini was a collaboration between the United States' NASA, the European Space Agency ("ESA"), and the Italian Space Agency ("ASI") to send a probe to study the Saturnian system, including the planet, its rings, and its natural satellites. The Flagship-class uncrewed robotic spacecraft comprised both NASA's Cassini probe, and ESA's Huygens lander which was designed to land on Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Cassini was the fourth space probe to visit Saturn and the first to enter its orbit. The craft were named after astronomers Giovanni Cassini and Christiaan Huygens.

The Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby (CRAF) was a cancelled plan for a NASA-led exploratory mission designed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory during the mid-to-late 1980s and early 1990s, that planned to send a spacecraft to encounter an asteroid, and then to rendezvous with a comet and fly alongside it for nearly three years. The project was eventually canceled when it went over budget; most of the money still left was redirected to its twin spacecraft, Cassini–Huygens, destined for Saturn, so it could survive Congressional budget cutbacks. Most of CRAF's scientific objectives were later accomplished by the smaller NASA spacecraft Stardust and Deep Impact, and by ESA's flagship Rosetta mission.

The exploration of Saturn has been solely performed by crewless probes. Three missions were flybys, which formed an extended foundation of knowledge about the system. The Cassini–Huygens spacecraft, launched in 1997, was in orbit from 2004 to 2017.

Titan Saturn System Mission (TSSM) was a joint NASA–ESA proposal for an exploration of Saturn and its moons Titan and Enceladus, where many complex phenomena were revealed by Cassini. TSSM was proposed to launch in 2020, get gravity assists from Earth and Venus, and arrive at the Saturn system in 2029. The 4-year prime mission would include a two-year Saturn tour, a 2-month Titan aero-sampling phase, and a 20-month Titan orbit phase.

The Saturn Atmospheric Entry Probe is a mission concept study for a robotic spacecraft to deliver a single probe into Saturn to study its atmosphere. The concept study was done to support the NASA 2010 Planetary Science Decadal Survey

A flyby is a spaceflight operation in which a spacecraft passes in proximity to another body, usually a target of its space exploration mission and/or a source of a gravity assist to impel it towards another target. Spacecraft which are specifically designed for this purpose are known as flyby spacecraft, although the term has also been used in regard to asteroid flybys of Earth for example. Important parameters are the time and distance of closest approach.

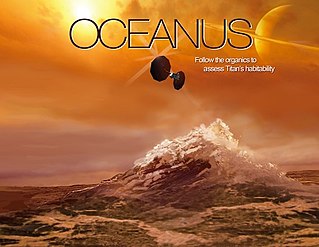

Oceanus is a NASA/JPL orbiter mission concept proposed in 2017 for the New Frontiers mission #4, but it was not selected for development. If selected at some future opportunity, Oceanus would travel to Saturn's moon Titan to assess its habitability. Studying Titan would help understand the early Earth and exoplanets which orbit other stars. The mission is named after Oceanus, the Greek god of oceans.

SPRITE was a proposed Saturn atmospheric probe mission concept of the NASA. SPRITE is a design for an atmospheric entry probe that would travel to Saturn from Earth on its own cruise stage, then enter the atmosphere of Saturn, and descend taking measurements in situ.

Neptune Odyssey is an orbiter mission concept to study Neptune and its moons, particularly Triton. The orbiter would enter into a retrograde orbit of Neptune to facilitate simultaneous study of Triton and would launch an atmospheric probe to characterize Neptune's atmosphere. The concept is being developed as a potential large strategic science mission for NASA by a team led by the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. The current proposal targets a launch in 2033 using the Space Launch System with arrival at Neptune in 2049, although trajectories using gravity assists at Jupiter have also been considered with launch dates in 2031.

The Enceladus Orbilander is a proposed NASA Flagship mission to Saturn's moon Enceladus. The Enceladus Orbilander would spend a year and a half orbiting Enceladus and sampling its water plumes, which stretch into space, before landing on the surface for a two-year mission to study materials for evidence of life. The mission, with an estimated cost of $4.9 billion, could launch in the late 2030s on a Space Launch System or Falcon Heavy with a landing in the early 2050s. It was proposed in the 2023–2032 Planetary Science Decadal Survey as the third highest priority Flagship mission, after the Uranus Orbiter and Probe and the Mars Sample Return program.

The retirement of a spacecraft refers to the discontinuation of a spacecraft from active service. This can involve deorbiting the spacecraft, discontinuing of the probes operations, passivating it, or loss of contact with it. One notable example of spacecraft retirement is Cassini's retirement in 2017.