William Goldman was an American novelist, playwright, and screenwriter. He first came to prominence in the 1950s as a novelist before turning to screenwriting. Among other accolades, Goldman won two Academy Awards in both writing categories: first for Best Original Screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and then for Best Adapted Screenplay for All the President's Men (1976).

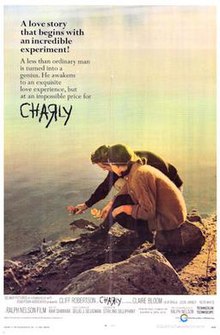

Clifford Parker Robertson III was an American actor whose career in film and television spanned over six decades. Robertson portrayed a young John F. Kennedy in the 1963 film PT 109, and won the 1968 Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in the film Charly.

Ralph Nelson was an American film and television director, producer, writer, and actor. He was best known for directing Lilies of the Field (1963), Father Goose (1964), and Charly (1968), films which won Academy Awards.

D.A.R.Y.L. is a 1985 science fiction adventure film directed by Simon Wincer and written by David Ambrose, Allan Scott, and Jeffrey Ellis. It stars Mary Beth Hurt, Michael McKean, Kathryn Walker, Colleen Camp, Josef Sommer, and Barret Oliver. It follows a seemingly normal young boy who turns out to be a top secret, military-created robot with superhuman abilities.

Papillon is a 1973 historical adventure drama prison film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner. The screenplay by Dalton Trumbo and Lorenzo Semple Jr. was based on the 1969 autobiography by the French convict Henri Charrière. The film stars Steve McQueen as Charrière ("Papillon") and Dustin Hoffman as Louis Dega. Because it was filmed at remote locations, the film was quite expensive for the time ($12 million), but it earned more than twice that in its first year of release. The film's title is French for "Butterfly", referring to Charrière's tattoo and nickname.

Daniel Keyes was an American writer who wrote the novel Flowers for Algernon. Keyes was given the Author Emeritus honor by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America in 2000.

Sleep-learning or sleep-teaching is an attempt to convey information to a sleeping person, typically by playing a sound recording to them while they sleep. Although sleep is considered an important period for memory consolidation, scientific research has concluded that sleep-learning is not possible. It appears frequently in fiction.

The Best Man is a 1964 American political drama film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner with a screenplay by Gore Vidal based on his 1960 play of the same title. Starring Henry Fonda, Cliff Robertson and Lee Tracy, the film details the seamy political maneuverings behind the nomination of a presidential candidate at their party's national convention. The supporting cast features Edie Adams, Margaret Leighton, Ann Sothern, Shelley Berman, Gene Raymond and Kevin McCarthy. Lee Tracy was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance and it was his final theatrically released film.

"HOMR" is the ninth episode of the twelfth season of the American animated television series The Simpsons. The 257th episode overall, it originally aired on the Fox network in the United States on January 7, 2001. In the episode, while working as a human guinea pig, Homer discovers the root cause of his subnormal intelligence: a crayon that was lodged in his brain ever since he was six-years-old. He decides to have it removed to increase his IQ, but soon learns that being intelligent is not always the same as being happy.

David Begelman was an American film producer, film executive and talent agent who was involved in a studio embezzlement scandal in the 1970s.

I Love You, Alice B. Toklas is a 1968 American romantic comedy film directed by Hy Averback and starring Peter Sellers. The film is set in the counterculture of the 1960s. The cast includes Joyce Van Patten, David Arkin, Jo Van Fleet, Leigh Taylor-Young and a cameo by the script's co-writer Paul Mazursky. The title refers to writer Alice B. Toklas, whose 1954 autobiographical cookbook had a recipe for "Haschich Fudge". The film's eponymous theme song was performed by sunshine pop group Harpers Bizarre.

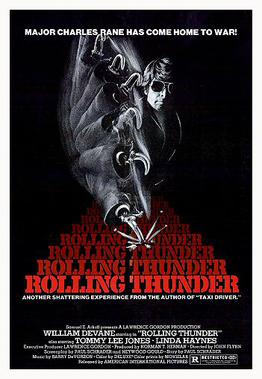

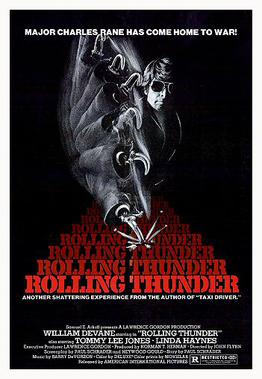

Rolling Thunder is a 1977 American psychological thriller film directed by John Flynn, from a screenplay by Paul Schrader and Heywood Gould, based on a story by Schrader. It was produced by Norman T. Herman, with Lawrence Gordon as executive producer. The film stars William Devane alongside Tommy Lee Jones, Linda Haynes, James Best, Dabney Coleman, and Luke Askew in supporting roles.

Ace Eli and Rodger of the Skies is a 1973 American adventure comedy film directed by John Erman from a screenplay by Claudia Salter. The film centers on a barnstorming pilot and his son as they fly around the United States in the 1920s, having adventures along the way. One of the driving forces behind the production, Robertson was a real life pilot, although Hollywood stunt pilot Frank Tallman flew most of the aerial scenes. The film was the first feature credit for filmmaker Steven Spielberg, who wrote the story.

Last of the Mobile Hot Shots is a 1970 American drama film. The screenplay by Gore Vidal is based on the Tennessee Williams play The Seven Descents of Myrtle, which opened on Broadway in March 1968 and ran for 29 performances.

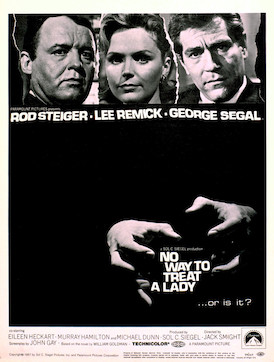

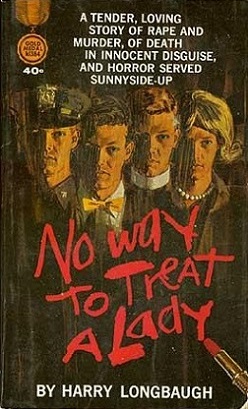

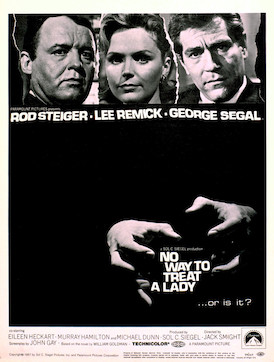

No Way to Treat a Lady is a 1968 American psychological thriller film with elements of black comedy, directed by Jack Smight, and starring Rod Steiger, Lee Remick, George Segal, and Eileen Heckart. Adapted by John Gay from William Goldman's 1964 novel of the same name, it follows a serial killer in New York City who impersonates various characters in order to gain the trust of women before murdering them.

Flowers for Algernon is a short story by American author Daniel Keyes, later expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adapted for film and other media. The short story, written in 1958 and first published in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960. The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that year's Nebula Award for Best Novel.

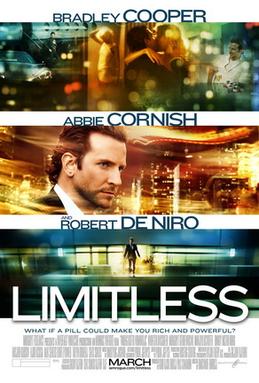

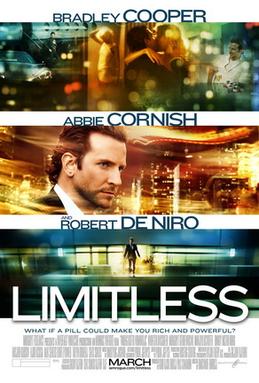

Limitless is a 2011 American science-fiction thriller film directed by Neil Burger and written by Leslie Dixon. Loosely based on the 2001 novel The Dark Fields by Alan Glynn, the film stars Bradley Cooper, Abbie Cornish, Robert De Niro, Andrew Howard, and Anna Friel. The film follows Edward Morra, a struggling writer who is introduced to a drug called NZT-48, which gives him the ability to use his brain fully which helps him vastly improve his lifestyle.

Masquerade is a 1965 British comedy thriller film directed by Basil Dearden based on the 1954 novel Castle Minerva by Victor Canning. It stars Cliff Robertson and Jack Hawkins and was filmed in the U.K. and in Spain.

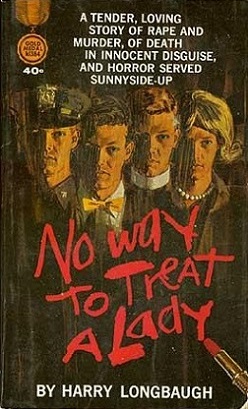

No Way to Treat a Lady is a 1964 novel by William Goldman.

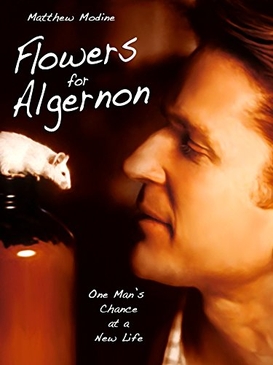

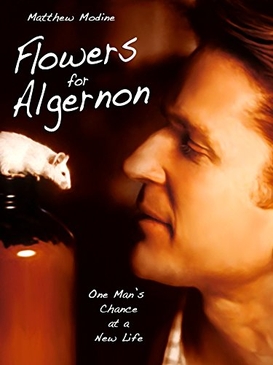

Flowers for Algernon is a 2000 American-Canadian television film written by John Pielmeier, directed by Jeff Bleckner and starring Matthew Modine. It is the second screen adaptation of Daniel Keyes' 1966 novel of the same name following the 1968 film Charly.