There has been a significant history of Chinese immigration to Canada, with the first settlement of Chinese people in Canada being in the 1780s. The major periods of Chinese immigration would take place from 1858 to 1923 and 1947 to the present day, reflecting changes in the Canadian government's immigration policy.

Chinese Canadians are Canadians of full or partial Chinese ancestry, which includes both naturalized Chinese immigrants and Canadian-born Chinese. They comprise a subgroup of East Asian Canadians which is a further subgroup of Asian Canadians. Demographic research tends to include immigrants from Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as overseas Chinese who have immigrated from Southeast Asia and South America into the broadly defined Chinese Canadian category.

The Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice (CCNC-SJ), known in the Chinese-Canadian community as Equal Rights Council (平權會), is an organization whose purpose is to monitor racial discrimination in Canada and to help young Chinese Canadians learn about their cultural history.

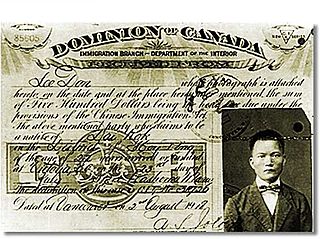

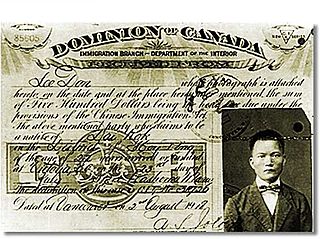

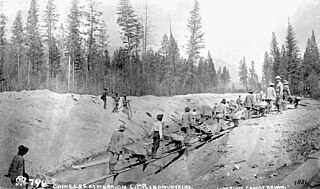

The Chinese Head Tax was a fixed fee charged to each Chinese person entering Canada. The head tax was first levied after the Canadian parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 and it was meant to discourage Chinese people from entering Canada after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The tax was abolished by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which outright prevented all Chinese immigration except for that of business people, clergy, educators, students, and some others.

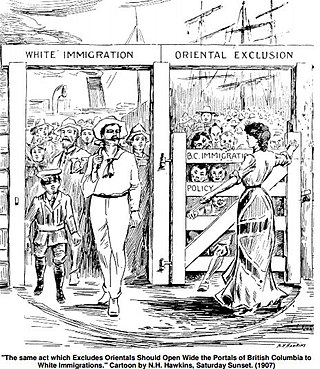

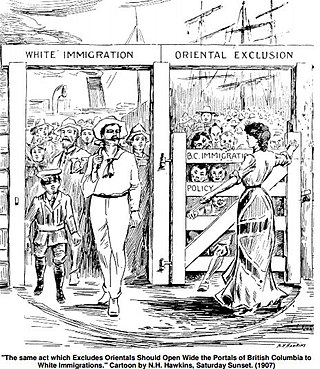

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, known today as the Chinese Exclusion Act, was an act passed by the government of Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, banning most forms of Chinese immigration to Canada. Immigration from most countries was controlled or restricted in some way, but only the Chinese were completely prohibited from immigrating to Canada.

From 1942 to 1949, Canada forcibly relocated and incarcerated over 22,000 Japanese Canadians—comprising over 90% of the total Japanese Canadian population—from British Columbia in the name of "national security". The majority were Canadian citizens by birth and were targeted based on their ancestry. This decision followed the events of the Japanese Empire's war in the Pacific against the Western Allies, such as the invasion of Hong Kong, the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, and the Fall of Singapore which led to the Canadian declaration of war on Japan during World War II. Similar to the actions taken against Japanese Americans in neighbouring United States, this forced relocation subjected many Japanese Canadians to government-enforced curfews and interrogations, job and property losses, and forced repatriation to Japan.

The Asiatic Exclusion League was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

Canadian immigration and refugee law concerns the area of law related to the admission of foreign nationals into Canada, their rights and responsibilities once admitted, and the conditions of their removal. The primary law on these matters is in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, whose goals include economic growth, family reunification, and compliance with humanitarian treaties.

The history of Vancouver is one that extends back thousands of years, with its first inhabitants arriving in the area following the Last Glacial Period. Vancouver is situated in British Columbia, Canada; with its location near the mouth of the Fraser River and on the waterways of the Strait of Georgia, Howe Sound, Burrard Inlet, and their tributaries. Vancouver has, for thousands of years, been a place of meeting, trade, and settlement.

Post-Confederation Canada (1867–1914) is history of Canada from the formation of the Dominion to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Canada had a population of 3.5 million, residing in the large expanse from Cape Breton to just beyond the Great Lakes, usually within a hundred miles or so of the Canada–United States border. One in three Canadians was French, and about 100,000 were aboriginal. It was a rural country composed of small farms. With a population of 115,000, Montreal was the largest city, followed by Toronto and Quebec at about 60,000. Pigs roamed the muddy streets of Ottawa, the small new national capital.

New Zealand imposed a poll tax on Chinese immigrants during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The poll tax was effectively lifted in the 1930s following the invasion of China by Japan, and was finally repealed in 1944. On 12 February 2002, Prime Minister at the time Helen Clark offered New Zealand's Chinese community an official apology for the poll tax.

The history of immigration to Canada details the movement of people to modern-day Canada. The modern Canadian legal regime was founded in 1867 but Canada also has legal and cultural continuity with French and British colonies in North America going back to the seventeenth century, and during the colonial era immigration was a major political and economic issue and Britain and France competed to fill their colonies with loyal settlers. Prior to that, the land that now makes up Canada was inhabited by many distinct Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples contributed significantly to the culture and economy of the early European colonies, to which was added several waves of European immigration. More recently, the source of migrants to Canada has shifted away from Europe and towards Asia and Africa. Canada's cultural identity has evolved constantly in tandem with changes in immigration patterns.

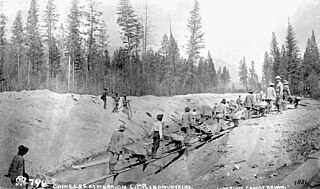

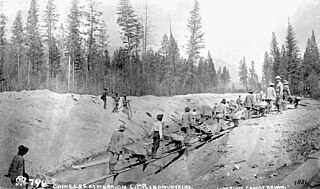

The Vancouver anti-Chinese riots of 1886, sometimes called the Winter Riots because of the time of year they took place, were prompted by the engagement of cheap Chinese labour by the Canadian Pacific Railway to clear Vancouver's West End of large Douglas fir trees and stumps, passing over the thousands of unemployed men from the rest of Canada who had arrived looking for work.

The continuous journey regulation was a restriction placed by the Canadian government that (ostensibly) prevented those who, "in the opinion of the Minister of the Interior," did not "come from the country of their birth or citizenship by a continuous journey and or through tickets purchased before leaving the country of their birth or nationality." However, in effect, the regulation would only affect the immigration of persons from India.

The Vancouver riots occurred September 7–9, 1907, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. At about the same time there were similar anti-Asian riots in San Francisco, Bellingham, Washington, and other West Coast cities. They were not coordinated, but instead reflected common underlying anti-immigration attitudes. Agitation for direct action was led by labour unions and small business. No one was killed but the damage to Asian-owned property was extensive. One result was an informal agreement whereby the government of China stopped emigration to Canada.

The history of Chinese Canadians in British Columbia began with the first recorded visit by Chinese people to North America in 1788. Some 30–40 men were employed as shipwrights at Nootka Sound in what is now British Columbia, to build the first European-type vessel in the Pacific Northwest, named the North West America. Large-scale immigration of Chinese began seventy years later with the advent of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858. During the gold rush, settlements of Chinese grew in Victoria and New Westminster and the "capital of the Cariboo" Barkerville and numerous other towns, as well as throughout the colony's interior, where many communities were dominantly Chinese. In the 1880s, Chinese labour was contracted to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Following this, many Chinese began to move eastward, establishing Chinatowns in several of the larger Canadian cities.

A White Man's Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 is a 1989 book by Patricia E. Roy, published by the University of British Columbia Press. It discusses late 19th and early 20th century anti-Asian sentiment within British Columbia. Politicians from British Columbia referred to the place as "a white man's province", and the book includes an analysis of the phrase itself. As of 1992 Roy was planning to create a sequel.

Avvy Yao-Yao Go is a Canadian lawyer and judge. She is known for her work advocating on behalf of immigrant and racialized communities in Canada. In 2014 she was appointed to the Order of Ontario. In August 2021, Go was appointed to the Federal Court.

The Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration was a commission of inquiry appointed to establish whether or not imposing restrictions to Chinese immigration to Canada was in the country's best interest. Ordered on 4 July 1884 by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, the inquiry was appointed two commissioners were: the Honorable Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, LL.D., who was the Secretary of State for Canada; and the Honorable John Hamilton Gray, DCL, a Justice on the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

East Asian Canadians are Canadians who were either born in or can trace their ancestry to East Asia. The term East Asian Canadian is a subgroup of Asian Canadians. According to Statistics Canada, East Asian Canadians are considered visible minorities and can be further divided by ethnicity and/or nationality, such as Chinese Canadian, Hong Kong Canadian, Japanese Canadian, Korean Canadian, Mongolian Canadian, Taiwanese Canadian or Tibetan Canadian, as seen on demi-decadal census data.